A Jan. 18, 2017 news item on Nanowerk describes research into an environmentally friendly air filter from Washington State University,

Washington State University researchers have developed a soy-based air filter that can capture toxic chemicals, such as carbon monoxide and formaldehyde, which current air filters can’t.

The research could lead to better air purifiers, particularly in regions of the world that suffer from very poor air quality. …

Working with researchers from the University of Science and Technology Beijing, the WSU team, including Weihong (Katie) Zhong, professor in the School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, and graduate student Hamid Souzandeh, used a pure soy protein along with bacterial cellulose for an all-natural, biodegradable, inexpensive air filter.

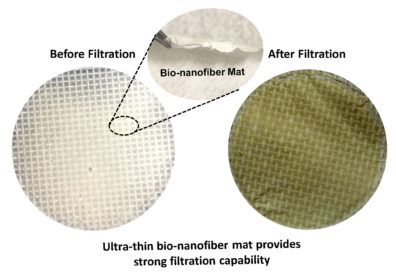

Here’s an image the researchers have made available,

A Jan. 12, 2017 Washington State University news release by Tilda Hilding, which originated the news item, expands on the theme,

Poor air quality causes health problems worldwide and is a factor in diseases such as asthma, heart disease and lung cancer. Commercial air purifiers aim for removing the small particles that are present in soot, smoke or car exhaust because these damaging particles are inhaled directly into the lungs.

With many sources of pollution in some parts of the world, however, air pollution also can contain a mix of hazardous gaseous molecules, such as carbon monoxide, formaldehyde, sulfur dioxide and other volatile organic compounds.

Typical air filters, which are usually made of micron-sized fibers of synthetic plastics, physically filter the small particles but aren’t able to chemically capture gaseous molecules. Furthermore, they’re most often made of glass and petroleum products, which leads to secondary pollution, Zhong said.

Soy captures nearly all pollutants

The WSU and Chinese team developed a new kind of air filtering material that uses natural, purified soy protein and bacterial cellulose – an organic compound produced by bacteria. The soy protein and cellulose are cost effective and already used in numerous applications, such as adhesives, plastic products, tissue regeneration materials and wound dressings.

Soy contains a large number of functional chemical groups – it includes 18 types of amino groups. Each of the chemical groups has the potential to capture passing pollution at the molecular level. The researchers used an acrylic acid treatment to disentangle the very rigid soy protein, so that the chemical groups can be more exposed to the pollutants.

The resulting filter was able to remove nearly all of the small particles as well as chemical pollutants, said Zhong.

Filters are economical, biodegradable

Especially in very polluted environments, people might be breathing an unknown mix of pollutants that could prove challenging to purify. But, with its large number of functional groups, the soy protein is able to attract a wide variety of polluting molecules.

“We can take advantage from those chemical groups to grab the toxics in the air,” Zhong said.

The materials are also cost-effective and biodegradable. Soybeans are among the most abundant plants in the world, she added.

Zhong occasionally visits her native China and has personally experienced the heavy pollution in Beijing as sunny skies turn to gray smog within a few days.

“Air pollution is a very serious health issue,” she said. “If we can improve indoor air quality, it would help a lot of people.”

Patents filed on filters, paper towels

In addition to the soy-based filters, the researchers have also developed gelatin- and cellulose-based air filters. They are also applying the filter material on top of low-cost and disposable paper towel to reinforce it and to improve its performance. They have filed patents on the technology and are interested in commercialization opportunities.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Soy protein isolate/bacterial cellulose composite membranes for high efficiency particulate air filtration by Xiaobing Liu, Hamid Souzandeh, Yudong Zheng, Yajie Xie, Wei-Hong Zhong, Cai Wang. Composites Science and Technology Volume 138, 18 January 2017, Pages 124–133 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2016.11.022

This paper is behind a paywall.