A May 2,2019 news item on Nanowerk describes some graphene-based artwork being created at Rice University (Texas, US), Note: A link has been removed,

When you read about electrifying art, “electrifying” isn’t usually a verb. But an artist working with a Rice University lab is in fact making artwork that can deliver a jolt.

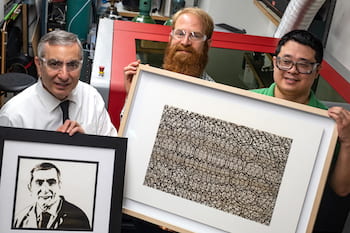

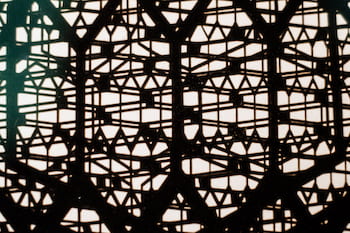

The Rice lab of chemist James Tour introduced laser-induced graphene (LIG) to the world in 2014, and now the researchers are making art with the technique, which involves converting carbon in a common polymer or other material into microscopic flakes of graphene.

…

A May 2, 2019 Rice university news release (also received via email), which originated the news item, describes laser-induced graphene (LIG) and the art in more detail (Note: Links have been removed),

LIG is metallic and conducts electricity. The interconnected flakes are effectively a wire that could empower electronic artworks.

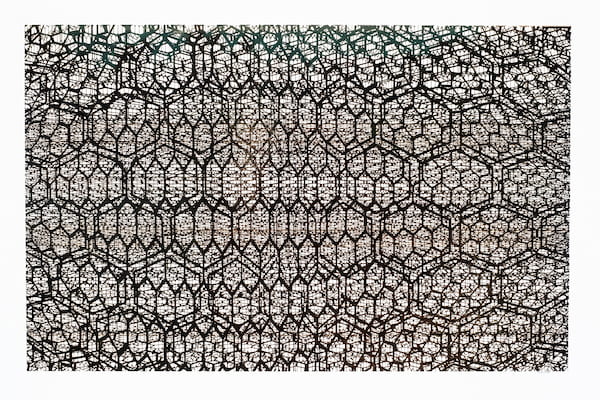

The paper in the American Chemical Society journal ACS Applied Nano Materials – simply titled “Graphene Art” – lays out how the lab and Houston artist and co-author Joseph Cohen generated LIG portraits and prints, including a graphene-inspired landscape called “Where Do I Stand?”

While the work isn’t electrified, Cohen said it lays the groundwork for future possibilities.

“That’s what I would like to do,” he said. “Not make it kitsch or play off the novelty, but to have it have some true functionality that allows greater awareness about the material and opens up the experience.”

Cohen created the design in an illustration program and sent it directly to the industrial engraving laser Tour’s lab uses to create LIG on a variety of materials. The laser burned the artist’s fine lines into the substrate, in this case archive-quality paper treated with fire retardant.

The piece, which was part of Cohen’s exhibit at Rice’s BioScience Research Collaborative last year, peers into the depths of what a viewer shrunken to nanoscale might see when facing a field of LIG, with overlapping hexagons – the basic lattice of atom-thick graphene – disappearing into the distance.

“You’re looking at this image of a 3D foam matrix of laser-induced graphene and it’s actually made of LIG,” he said. “I didn’t base it on anything; I was just thinking about what it would look like. When I shared it with Jim, he said, ‘Wow, that’s what it would look like if you could really blow this up.’”

Cohen said his art is about media specificity.

“In terms of the artistic application, you’re not looking at a representation of something, as traditionally we would in the history of art,” he said. “Each piece is 100% original. That’s the key.”

He developed an interest in nanomaterials as media for his art when he began work with Rice alumnus Daniel Heller, a bioengineer at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York who established an artist-in-residency position in his lab.

After two years of creating with carbon nanotube-infused paint, Cohen attended an Electrochemical Society conference and met Tour, who in turn introduced him to Rice chemists Bruce Weisman and Paul Cherukuri, who further inspired his investigation of nanotechnology.The rest is art history.

It would be incorrect to think of the process as “printing,” Tour said. Instead of adding a substance to the treated paper, substance is burned away as the laser turns the surface into foamlike flakes of interconnected graphene.

The art itself can be much more than eye candy, given LIG’s potential for electronic applications like sensors or as triboelectric generators that turn mechanical actions into current.

“You could put LIG on your back and have it flash LEDs with every step you take,” Tour said.

The fact that graphene is a conductor — unlike paint, ink or graphite from a pencil — makes it particularly appealing to Cohen, who expects to take advantage of that capability in future works.

“It’s art with a capital A that is trying to do the most that it can with advancements in science and technology,” he said. “If we look back historically, from the Renaissance to today, the highest forms of art push the limits of human understanding.”

…

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Graphene Art by Yieu Chyan, Joseph Cohen, Winston Wang, Chenhao Zhang, and James M. Tour. ACS Appl. Nano Mater., Article ASAP DOI: 10.1021/acsanm.9b00391 Publication Date (Web): April 23, 2019

Copyright © 2019 American Chemical Society

This paper appears to be open access.

Because I can’t resist the delight beaming from these faces,