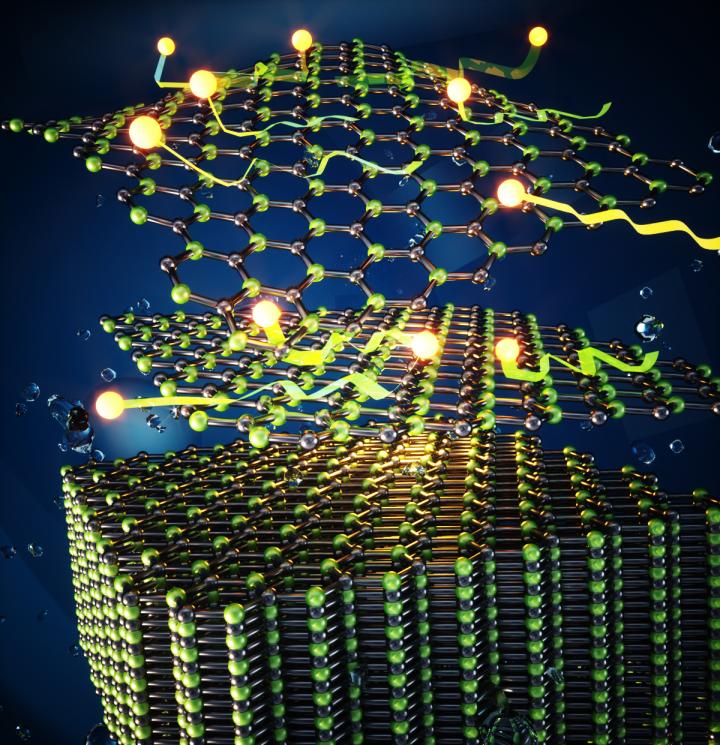

Rice University (Texas, US) has a pretty image illustrating the process of making 2D nanoflakes,

A January 27, 2021 news item on Nanowerk announces the Rice University news,

Just a little soap helps clean up the challenging process of preparing two-dimensional hexagonal boron nitride (hBN).

Rice University chemists have found a way to get the maximum amount [number] of quality 2D hBN nanosheets from its natural bulk form by processing it with surfactant (aka soap) and water. The surfactant surrounds and stabilizes the microscopic flakes, preserving their properties.

Experiments by the lab of Rice chemist Angel Martí identified the “sweet spot” for making stable dispersions of hBN, which can be processed into very thin antibacterial films that handle temperatures up to 900 degrees Celsius (1,652 degrees Fahrenheit).

…

A brief grammatical moment: I can see where someone might view it as arguable (see second paragraph of the above excerpt) but for me ‘amount’ is for something like ‘flour’ for an ‘amount of flour’. ‘Number’ is for something like a ‘number of sheets’. The difference lies in your ability to count the items. Generally speaking, you can’t count the number of flour, therefore, it’s the amount of flour, but you can count the number of sheets. Can count these hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) sheets? If not, is what makes this arguable.

A January 27, 2021 Rice University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, delves into details,

The work led by Martí, alumna Ashleigh Smith McWilliams and graduate student Cecilia Martínez-Jiménez is detailed in the American Chemical Society journal ACS Applied Nano Materials.

“Boron nitride materials are interesting, particularly because they are extremely resistant to heat,” Martí said. “They are as light as graphene and carbon nanotubes, but you can put hBN in a flame and nothing happens to it.”

He said bulk hBN is cheap and easy to obtain, but processing it into microscopic building blocks has been a challenge. “The first step is to be able to exfoliate and disperse them, but research on how to do that has been scattered,” Martí said. “When we decided to set a benchmark, we found the processes that have been extremely useful for graphene and nanotubes don’t work as well for boron nitride.”

Sonicating bulk hBN in water successfully exfoliated the material and made it soluble. “That surprised us, because nanotubes or graphene just float on top,” Martí said. “The hBN dispersed throughout, though they weren’t particularly stable.

“It turned out the borders of boron nitride crystals are made of amine and nitric oxide groups and boric acid, and all of these groups are polar (with positive or negative charge),” he said. “So when you exfoliate them, the edges are full of these functional groups that really like water. That never happens with graphene.”

Experiments with nine surfactants helped them find just the right type and amount to keep 2D hBN from clumping without cutting individual flakes too much during sonication. The researchers used 1% by weight of each surfactant in water, added 20 milligrams of bulk hBN, then stirred and sonicated the mix.

Spinning the resulting solutions at low and high rates showed the greatest yield came with the surfactant known as PF88 under 100-gravity centrifugation, but the highest-quality nanosheets came from all the ionic surfactants under 8,000 g centrifugation, with the greatest stability from common ionic surfactants SDS and CTAC.

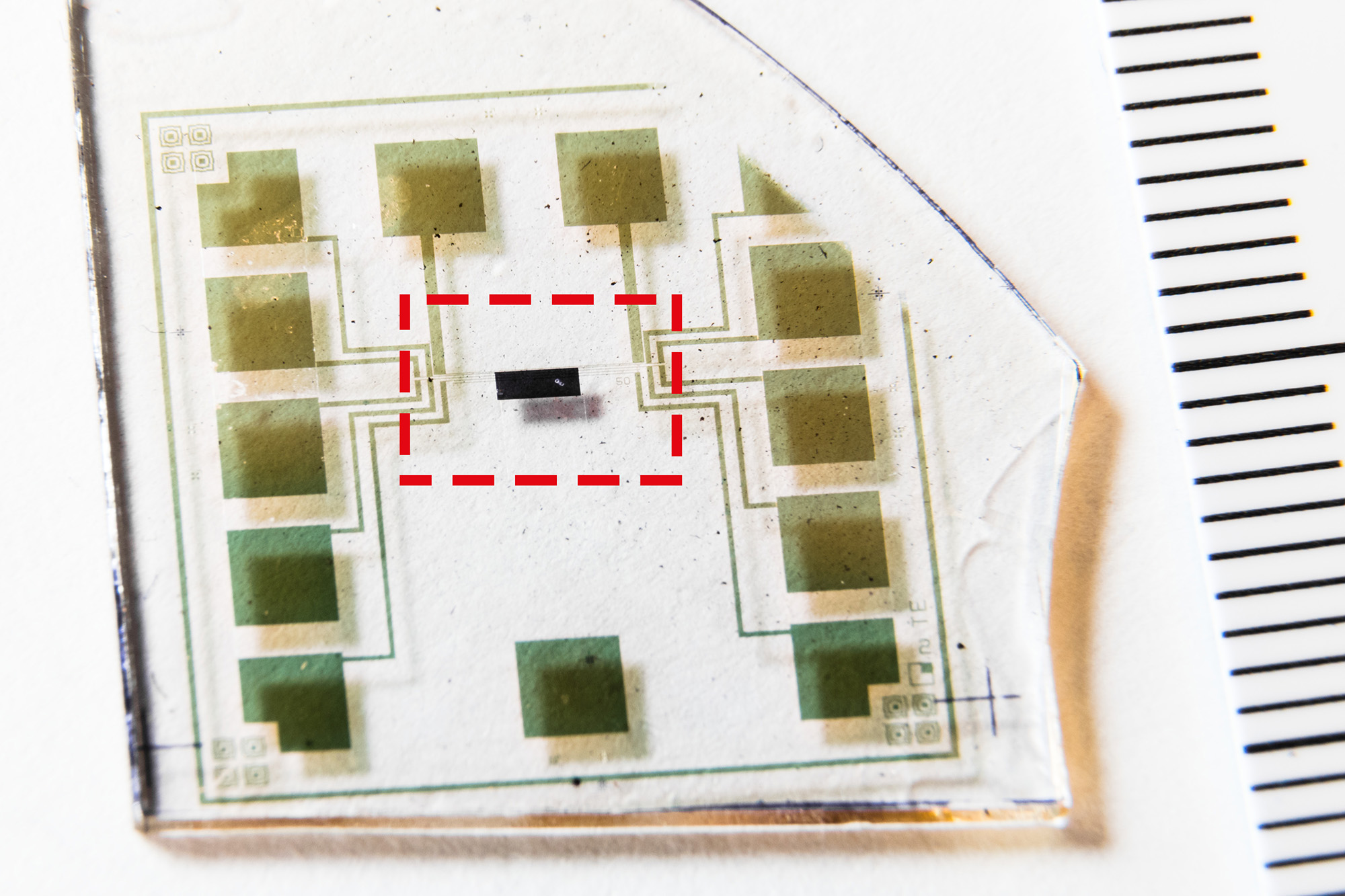

DTAB — short for dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide — under high centrifugation proved best at balancing the yield and quality of 2D hBN. The researchers also produced a transparent film from hBN nanosheets dispersed in SDS and water to demonstrate how they can be processed into useful products.

“We describe the steps you need to do to produce high-quality hBN flakes,” Martí said. “All of the steps are important, and we were able to bring to light the consequences of each one.”

Understanding the Exfoliation and Dispersion of Hexagonal Boron Nitride Nanosheets by Surfactants: Implications for Antibacterial and Thermally Resistant Coatings by Ashleigh D. Smith McWilliams, Cecilia Martínez-Jiménez, Asia Matatyaho Ya’akobi, Cedric J. Ginestra, Yeshayahu Talmon, Matteo Pasquali, and Angel A. Martí. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 1, 142–151 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.0c02437 Publication Date: January 7, 2021 Copyright © 2021 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.