An October 24, 2022 news item on ScienceDaily highlights research into better understanding problems with ‘good’ CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) gene editing,

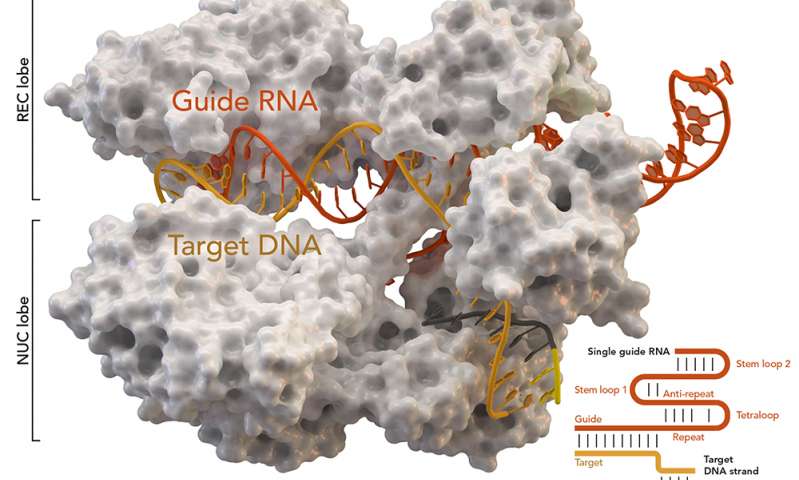

A Rice University lab is leading the effort to reveal potential threats to the efficacy and safety of therapies based on CRISPR-Cas9, the Nobel Prize-winning gene editing technique, even when it appears to be working as planned.

Bioengineer Gang Bao of Rice’s George R. Brown School of Engineering and his team point out in a paper published in Science Advances that while off-target edits to DNA have long been a cause for concern, unseen changes that accompany on-target edits also need to be recognized — and quantified.

Bao noted a 2018 Nature Biotechnology paper indicated the presence of large deletions. “That’s when we started looking into what we can do to quantify them, due to CRISPR-Cas9 systems designed for treating sickle cell disease,” he said.

…

An October 24, 2022 Rice University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, details the concerns (Note: Links have been removed),

Bao has been a strong proponent of CRISPR-Cas9 as a tool to treat sickle cell disease, a quest that has brought him and his colleagues ever closer to a cure. Now the researchers fear that large deletions or other undetected changes due to gene editing could persist in stem cells as they divide and differentiate, thus have long-term implications for health.

“We do not have a good understanding of why a few thousand bases of DNA at the Cas9 cut site can go missing and the DNA double-strand breaks can still be rejoined efficiently,” Bao said. “That’s the first question, and we have some hypotheses. The second is, what are the biological consequences? Large deletions (LDs) can reach to nearby genes and disrupt the expression of both the target gene and the nearby genes. It is unclear if LDs could result in the expression of truncated proteins.

“You could also have proteins that misfold, or proteins with an extra domain because of large insertions,” he said. “All kinds of things could happen, and the cells could die or have abnormal functions.”

His lab developed a procedure that uses single-molecule, real-time (SMRT) sequencing with dual unique molecular identifiers (UMI) to find and quantify unintended LDs along with large insertions and local chromosomal rearrangements that accompany small insertions/deletions (INDELs) at a Cas9 on-target cut site.

“To quantify large gene modifications, we need to perform long-range PCR, but that could induce artifacts during DNA amplification,” Bao said. “So we used UMIs of 18 bases as a kind of barcode.”

“We add them to the DNA molecules we want to amplify to identify specific DNA molecules as a way to reduce or eliminate artifacts due to long-range PCR,” he said. “We also developed a bioinformatics pipeline to analyze SMRT sequencing data and quantified the LDs and large insertions.”

The Bao lab’s tool, called LongAmp-seq (for long-amplicon sequencing), accurately quantifies both small INDELs and large LDs. Unlike SMRT-seq, which requires the use of a long-read sequencer often only available at a core facility, LongAmp-seq can be performed using a short-read sequencer.

To test the strategy, the lab team led by Rice alumna Julie Park, now an assistant research professor of bioengineering, used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 to edit beta-globin (HBB), gamma-globin (HBG) and B-cell lymphoma/leukemia 11A (BCL11A) enhancers in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPC) from patients with sickle cell disease, and the PD-1 gene in primary T-cells.

They found large deletions of up to several thousand bases occurred at high frequency in HSPCs: up to 35.4% in HBB, 14.3% in HBG and 15.2% in BCL11A genes, as well as on the PD-1 (15.2%) gene in T-cells.

Since two of the specific CRISPR guide RNAs tested by the Bao lab are being used in clinical trials to treat sickle cell disease, he said it’s important to determine the biological consequences of large gene modifications due to Cas9-induced double-strand breaks.

Bao said the Rice team is currently looking downstream to analyze the consequences of long deletions on messenger RNA, the mediator that carries code for ribosomes to make proteins. “Then we’ll move on to the protein level,” Bao said. “We want to know if these large deletions and insertions persist after the gene-edited HSPCs are transplantation into mice and patients.”

Co-authors of the study from Rice are graduate students Mingming Cao and Yilei Fu, alumni Yidan Pan and Timothy Davis, research specialist Lavanya Saxena, microscopist/bioinstrumentation specialist Harshavardhan Deshmukh and Todd Treangen, an assistant professor of computer science, and Emory University’s Vivien Sheehan, an associate professor of pediatrics.

Bao is the department chair and Foyt Family Professor of Bioengineering, a professor of chemistry, materials science and nanoengineering, and mechanical engineering, and a CPRIT Scholar in Cancer Research.

The National Institutes of Health (R01HL152314, OT2HL154977) supported the research.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the latest paper,

Comprehensive analysis and accurate quantification of unintended large gene modifications induced by CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing by So Hyun Park, Mingming Cao, Yidan Pan, Timothy H. Davis, Lavanya Saxena, Harshavardhan Deshmukh, Yilei Fu, Todd Treangen, Vivien A. Sheehan, and Gang Bao. Science Advances Vol 8, Issue 42 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abo7676 First published online: 21 Oct 2022 Published in print: March 3, 2023

This paper is behind a paywall.