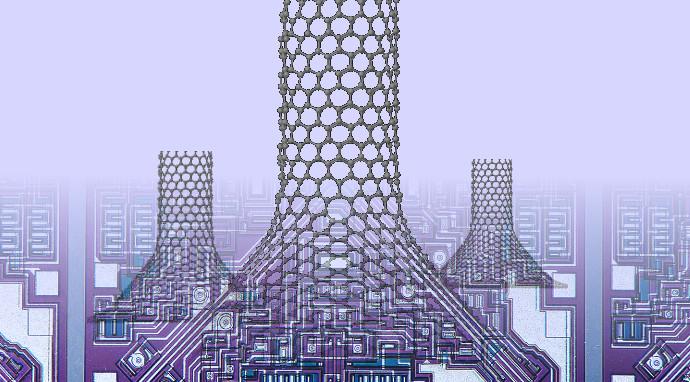

A November 9, 2022 Rice University news release (also on EurekAlert) announces the Holy Grail (I’ve lost track of how many have been reached) has been achieved for growing batches of carbon nanotubes,

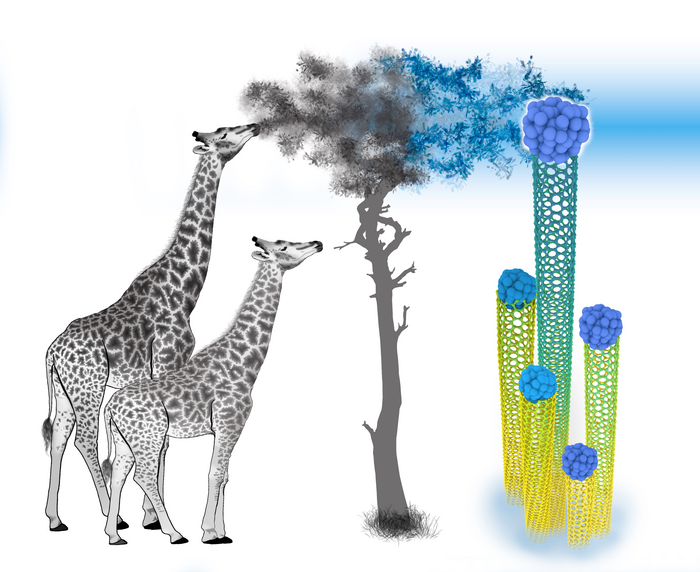

Like a giraffe stretching for leaves on a tall tree, making carbon nanotubes reach for food as they grow may lead to a long-sought breakthrough.

Materials theorists Boris Yakobson and Ksenia Bets at Rice University’s George R. Brown School of Engineering show how putting constraints on growing nanotubes could facilitate a “holy grail” of growing batches with a single desired chirality.

Their paper in Science Advances describes a strategy by which constraining the carbon feedstock in a furnace would help control the “kite” growth of nanotubes. In this method, the nanotube begins to form at the metal catalyst on a substrate, but lifts the catalyst as it grows, resembling a kite on a string.

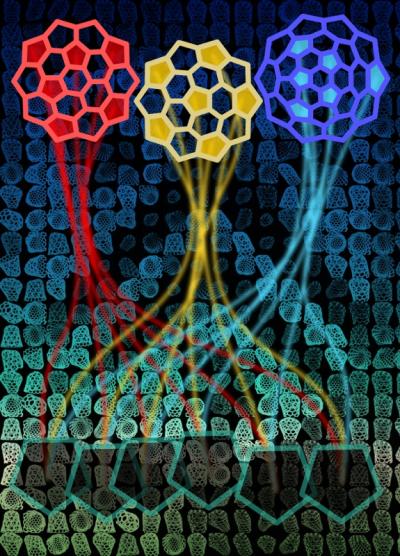

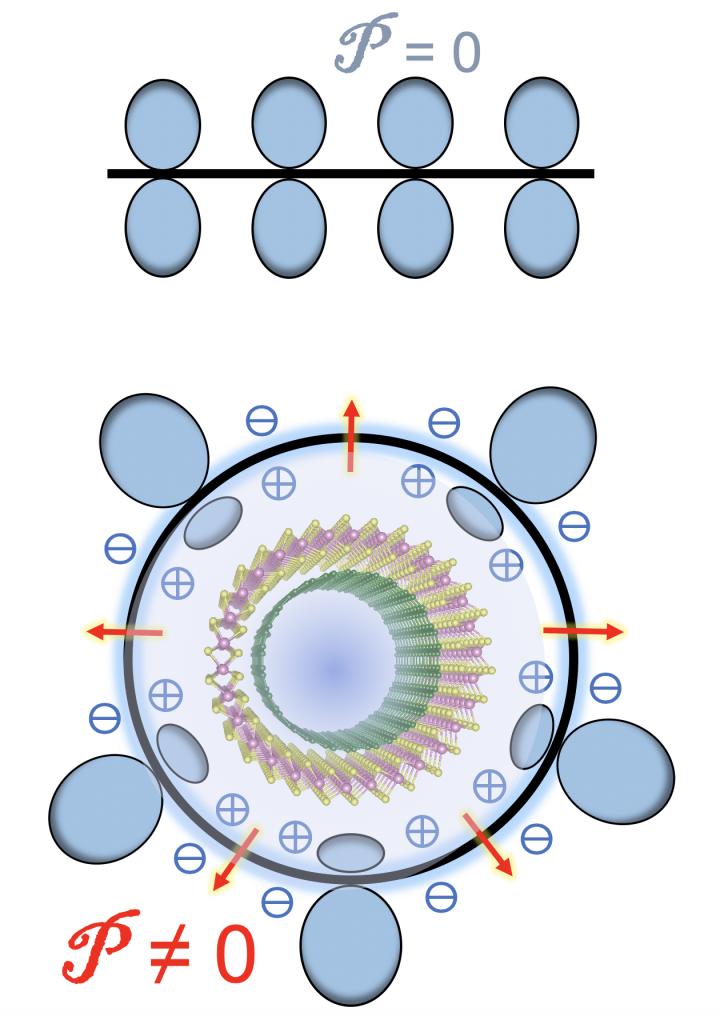

Carbon nanotube walls are basically graphene, its hexagonal lattice of atoms rolled into a tube. Chirality refers to how the hexagons are angled within the lattice, between 0 and 30 degrees. That determines whether the nanotubes are metallic or semiconductors. The ability to grow long nanotubes in a single chirality could, for instance, enable the manufacture of highly conductive nanotube fibers or semiconductor channels of transistors.

Normally, nanotubes grow in random fashion with single and multiple walls and various chiralities. That’s fine for some applications, but many need “purified” batches that require centrifugation or other costly strategies to separate the nanotubes.

The researchers suggested hot carbon feedstock gas fed through moving nozzles could effectively lead nanotubes to grow for as long as the catalyst remains active. Because tubes with different chiralities grow at different speeds, they could then be separated by length, and slower-growing types could be completely eliminated.

One additional step that involves etching away some of the nanotubes could then allow specific chiralities to be harvested, they determined.

The lab’s work to define the mechanisms of nanotube growth led them to think about whether the speed of growth as a function of individual tubes’ chirality could be useful. The angle of “kinks” in the growing nanotubes’ edges determines how energetically amenable they are to adding new carbon atoms.

“The catalyst particles are moving as the nanotubes grow, and that’s principally important,” said lead author Bets, a researcher in Yakobson’s group. “If your feedstock keeps moving away, you get a moving window where you’re feeding some tubes and not the others.”

The paper’s reference to Lamarck giraffes — a 19th-century theory of how they evolved such long necks — isn’t entirely out of left field, Bets said.

“It works as a metaphor because you move your ‘leaves’ away and the tubes that can reach it continue growing fast, and those that cannot just die out,” she said. “Eventually, all the nanotubes that are just a tiny bit slow will ‘die.’”

Speed is only part of the strategy. In fact, they suggest nanotubes that are a little slower should be the target to assure a harvest of single chiralities.

Because nanotubes of different chiralities grow at their own rates, a batch would likely exhibit tiers. Chemically etching the longest nanotubes would degrade them, preserving the next level of tubes. Restoring the feedstock could then allow the second-tier nanotubes to continue growing until they are ready to be culled, Bets said.

“There are three or four laboratory studies that show nanotube growth can be reversed, and we also know it can be restarted after etching,” she said. “So all the parts of our idea already exist, even if some of them are tricky. Close to equilibrium, you will have the same proportionality between growth and etching speeds for the same tubes. If it’s all nice and clean, then you can absolutely, precisely pick the tubes you target.”

The Yakobson lab won’t make them, as it focuses on theory, not experimentation. But other labs have turned past Rice theories into products like boron buckyballs.

“I’m pretty sure every single one of our reviewers were experimentalists, and they didn’t see any contradictions to it working,” Bets said. “Their only complaint, of course, was that they would like experimental results right now, but that’s not what we do.”

She hopes more than a few labs will pick up the challenge. “In terms of science, it’s usually more beneficial to give ideas to the crowd,” Bets said. “That way, those who have interest can do it in 100 different variations and see which one works. One guy trying it might take 100 years.”

Yakobson added, “We don’t want to be that ‘guy.’ We don’t have that much time.”

…

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Single-chirality nanotube synthesis by guided evolutionary selection by Boris I. Yakobson and Ksenia V. Bets. Science Advances 9 Nov 2022 Vol 8, Issue 45 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.add4627

This paper is open access.

![[downloaded from http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/nl5017317]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/CarbyneMorphs-300x166.gif)