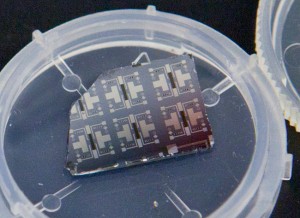

Researchers have developed a more complex memristor device than has been the case according to an April 6, 2015 Northwestern University news release (also on EurekAlert),

Researchers are always searching for improved technologies, but the most efficient computer possible already exists. It can learn and adapt without needing to be programmed or updated. It has nearly limitless memory, is difficult to crash, and works at extremely fast speeds. It’s not a Mac or a PC; it’s the human brain. And scientists around the world want to mimic its abilities.

Both academic and industrial laboratories are working to develop computers that operate more like the human brain. Instead of operating like a conventional, digital system, these new devices could potentially function more like a network of neurons.

“Computers are very impressive in many ways, but they’re not equal to the mind,” said Mark Hersam, the Bette and Neison Harris Chair in Teaching Excellence in Northwestern University’s McCormick School of Engineering. “Neurons can achieve very complicated computation with very low power consumption compared to a digital computer.”

A team of Northwestern researchers, including Hersam, has accomplished a new step forward in electronics that could bring brain-like computing closer to reality. The team’s work advances memory resistors, or “memristors,” which are resistors in a circuit that “remember” how much current has flowed through them.

…

“Memristors could be used as a memory element in an integrated circuit or computer,” Hersam said. “Unlike other memories that exist today in modern electronics, memristors are stable and remember their state even if you lose power.”

Current computers use random access memory (RAM), which moves very quickly as a user works but does not retain unsaved data if power is lost. Flash drives, on the other hand, store information when they are not powered but work much slower. Memristors could provide a memory that is the best of both worlds: fast and reliable. But there’s a problem: memristors are two-terminal electronic devices, which can only control one voltage channel. Hersam wanted to transform it into a three-terminal device, allowing it to be used in more complex electronic circuits and systems.

The memristor is of some interest to a number of other parties prominent amongst them, the University of Michigan’s Professor Wei Lu and HP (Hewlett Packard) Labs, both of whom are mentioned in one of my more recent memristor pieces, a June 26, 2014 post.

Getting back to Northwestern,

Hersam and his team met this challenge by using single-layer molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), an atomically thin, two-dimensional nanomaterial semiconductor. Much like the way fibers are arranged in wood, atoms are arranged in a certain direction–called “grains”–within a material. The sheet of MoS2 that Hersam used has a well-defined grain boundary, which is the interface where two different grains come together.

“Because the atoms are not in the same orientation, there are unsatisfied chemical bonds at that interface,” Hersam explained. “These grain boundaries influence the flow of current, so they can serve as a means of tuning resistance.”

When a large electric field is applied, the grain boundary literally moves, causing a change in resistance. By using MoS2 with this grain boundary defect instead of the typical metal-oxide-metal memristor structure, the team presented a novel three-terminal memristive device that is widely tunable with a gate electrode.

“With a memristor that can be tuned with a third electrode, we have the possibility to realize a function you could not previously achieve,” Hersam said. “A three-terminal memristor has been proposed as a means of realizing brain-like computing. We are now actively exploring this possibility in the laboratory.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Gate-tunable memristive phenomena mediated by grain boundaries in single-layer MoS2 by Vinod K. Sangwan, Deep Jariwala, In Soo Kim, Kan-Sheng Chen, Tobin J. Marks, Lincoln J. Lauhon, & Mark C. Hersam. Nature Nanotechnology (2015) doi:10.1038/nnano.2015.56 Published online 06 April 2015

This paper is behind a paywall but there is a few preview available through ReadCube Access.

Dexter Johnson has written about this latest memristor development in an April 9, 2015 posting on his Nanoclast blog (on the IEEE [Institute for Electrical and Electronics Engineers] website) where he notes this (Note: A link has been removed),

The memristor seems to generate fairly polarized debate, especially here on this website in the comments on stories covering the technology. The controversy seems to fall along the lines that the device that HP Labs’ Stan Williams and Greg Snider developed back in 2008 doesn’t exactly line up with the original theory of the memristor proposed by Leon Chua back in 1971.

It seems the ‘debate’ has evolved from issues about how the memristor is categorized. I wonder if there’s still discussion about whether or not HP Labs is attempting to develop a patent thicket of sorts.

![A nanocomponent that is capable of learning: The Bielefeld memristor built into a chip here is 600 times thinner than a human hair. [ downloaded from http://ekvv.uni-bielefeld.de/blog/uninews/entry/blueprint_for_an_artificial_brain]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/memristo_Bielefeld.jpeg)