I have three frog-oriented items and while they’re not strictly speaking in my usual range of topics, given this blog’s name and the fact I haven’t posted a frog piece in quite a while, it seems this is a good moment to address that lack.

Monitoring frogs and amphibians at Trent University (Ontario, Canada)

From a March 23, 2015 Trent University news release,

With the decline of amphibian populations around the world, a team of researchers led by Trent University’s Dr. Dennis Murray will seek to establish environmental DNA (eDNA) monitoring of amphibian occupancy and aquatic ecosystem risk assessment with the help of a significant grant of over $596,000 from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

Awarded to Professor Murray, a Canada research chair in integrative wildlife conservation, bioinformatics, and ecological modelling and professor at Trent University along with colleagues Dr. Craig Brunetti of the Biology department, and Dr. Chris Kyle of the Forensic Science program, and partners at Laurentian University, University of Toronto, McGill University, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry and Environment Canada, the grant will support the development of tools that will promote a cleaner aquatic environment.

The project will use amphibian DNA found in natural breeding habitats to determine the presence and abundance of amphibians as well as their pathogens. This new technology capitalizes on Trent University’s expertise and infrastructure in the areas of wildlife DNA and water quality.

“We’re honoured to have received the grant to help us drive the project forward,” said Prof. Murray. “Our plan is to place Canada, and Trent, in a leadership position with respect to aquatic wildlife monitoring and amphibian conservation.”

Amphibian populations are declining worldwide, yet in Canada, amphibian numbers are not monitored closely, meaning changes in their distribution or abundance may be unnoticeable. Amphibian monitoring in Canada is conducted by citizen scientists who record frog breeding calls when visiting bodies of water during the spring. However, the lack of formalized amphibian surveys leaves Canada in a vulnerable position regarding the status of its diverse amphibian community.

Prof. Murray believes that the protocols developed from this project could revolutionize how amphibian populations are monitored in Canada and in turn lead to new insights regarding the population trends for several amphibian species across the country.

Here’s more about NSERC and Trent University from the news release,

About NSERC

NSERC is a federal agency that helps make Canada a country of discoverers and innovators. The agency supports almost 30,000 post-secondary students and postdoctoral fellows in their advanced studies. NSERC promotes discovery by funding approximately 12,000 professors every year and fosters innovation by encouraging over 2,400 Canadian companies to participate and invest in post-secondary research projects.

The NSERC Strategic Project Grants aim to increase research and training in areas that could strongly influence Canada’s economy, society or environment in the next 10 years in four target areas: environmental science and technologies; information and communications technologies; manufacturing; and natural resources and energy.

About Trent University

One of Canada’s top universities, Trent University was founded on the ideal of interactive learning that’s personal, purposeful and transformative. Consistently recognized nationally for leadership in teaching, research and student satisfaction, Trent attracts excellent students from across the country and around the world. Here, undergraduate and graduate students connect and collaborate with faculty, staff and their peers through diverse communities that span residential colleges, classrooms, disciplines, hands-on research, co-curricular and community-based activities. Across all disciplines, Trent brings critical, integrative thinking to life every day. As the University celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2014/15, Trent’s unique approach to personal development through supportive, collaborative community engagement is in more demand than ever. Students lead the way by co-creating experiences rooted in dialogue, diverse perspectives and collaboration. In a learning environment that builds life-long passion for inclusion, leadership and social change, Trent’s students, alumni, faculty and staff are engaged global citizens who are catalysts in developing sustainable solutions to complex issues. Trent’s Peterborough campus boasts award-winning architecture in a breathtaking natural setting on the banks of the Otonabee River, just 90 minutes from downtown Toronto, while Trent University Durham delivers a distinct mix of programming in the GTA.

Trent University’s expertise in water quality could be traced to its proximity to Canada’s Experimental Lakes Area (ELA), a much beleaguered research environment due to federal political imperatives. You can read more about the area and the politics in this Wikipedia entry. BTW, I am delighted to learn that it still exists under the auspices of the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD),

Taking this post into nanotechnology territory while mentioning the ELA, Trent University published a Dec. 8, 2014 news release about research into silver nanoparticles,

For several years, Trent University’s Dr. Chris Metcalfe and Dr. Maggie Xenopoulos have dedicated countless hours to the study of aquatic contaminants and the threat they pose to our environment.

Now, through the efforts of the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), their research is reaching a wider audience thanks to a new video (Note: A link has been removed).

The video is one of a five-part series being released by the IISD that looks into environmental issues in Canada. The video entitled “Distilling Science at the Experimental Lakes Area: Nanosilver” and featuring Professors Metcalfe and Xenopoulos profiles their research around nanomaterials at the Experimental Lakes Area.

Prof. Xenopolous’ involvement in the project falls in line with other environmental issues she has tackled. In the past, her research has examined how human activities – including climate change, eutrophication and land use – affect ecosystem structure and function in lakes and rivers. She has also taken an interest in how land use affects the material exported and processed in aquatic ecosystems.

Prof. Metcalfe’s ongoing research on the fate and distribution of pharmaceutical and personal care products in the environment has generated considerable attention both nationally and internationally.

Together, their research into nanomaterials is getting some attention. Nanomaterials are submicroscopic particles whose physical and chemical properties make them useful for a variety of everyday applications. They can be found in certain pieces of clothing, home appliances, paint, and kitchenware. Initial laboratory research conducted at Trent University showed that nanosilver could strongly affect aquatic organisms at the bottom of the food chain, such as bacteria, algae and zooplankton.

To further examine these effects in a real ecosystem, a team of researchers from Trent University, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Environment Canada has been conducting studies at undisclosed lakes in northwestern Ontario. The Lake Ecosystem Nanosilver (LENS) project has been monitoring changes in the lakes’ ecosystem that occur after the addition of nanosilver.

“In our particular case, we will be able to study and understand the effects of only nanosilver because that is the only variable that is going to change,” says Prof. Xenopoulos. “It’s really the only place in the world where we can do that.”

The knowledge gained from the study will help policy-makers make decisions about whether nanomaterials can be a threat to aquatic ecosystems and whether regulatory action is required to control their release into the environment.

You can find the 13 mins. video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_nJai_B4YH0#action=share

Shapeshifting frogs, a new species in Ecuador

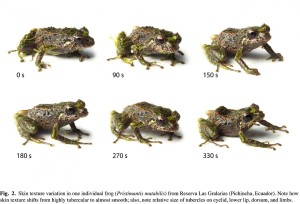

Caption: This image shows skin texture variation in one individual frog (Pristimantis mutabilis) from Reserva Las Gralarias. Note how skin texture shifts from highly tubercular to almost smooth; also note the relative size of the tubercles on the eyelid, lower lip, dorsum and limbs.

Credit: Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society

Here’s more about the shapeshifting and how the scientists figured out what the frogs were doing (from a March 23, 2015 Case Western Research University news release on EurekAlert; Note: A link has been removed),

A frog in Ecuador’s western Andean cloud forest changes skin texture in minutes, appearing to mimic the texture it sits on.

Originally discovered by a Case Western Reserve University PhD student and her husband, a projects manager at Cleveland Metroparks’ Natural Resources Division, the amphibian is believed to be the first known to have this shape-shifting capability.

But the new species, called Pristimantis mutabilis, or mutable rainfrog, has company. Colleagues working with the couple recently found that a known relative of the frog shares the same texture-changing quality–but it was never reported before.

The frogs are found at Reserva Las Gralarias, a nature reserve originally created to protect endangered birds in the Parish of Mindo, in north-central Ecuador.

The researchers, Katherine and Tim Krynak, and colleagues from Universidad Indoamérica and Tropical Herping (Ecuador) co-authored a manuscript describing the new animal and skin texture plasticity in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society this week. They believe their findings have broad implications for how species are and have been identified. The process may now require photographs and longer observations in the field to ensure the one species is not mistakenly perceived as two because at least two species of rain frogs can change their appearance.

Katherine Krynak believes the ability to change skin texture to reflect its surroundings may enable P. mutabilis to help camouflage itself from birds and other predators.

The Krynaks originally spotted the small, spiny frog, nearly the width of a marble, sitting on a moss-covered leaf about a yard off the ground on a misty July night in 2009. The Krynaks had never seen this animal before, though Tim had surveyed animals on annual trips to Las Gralarias since 2001, and Katherine since 2005.

They captured the little frog and tucked it into a cup with a lid before resuming their nightly search for wildlife. They nicknamed it “punk rocker” because of the thorn-like spines covering its body.

The next day, Katherine Krynak pulled the frog from the cup and set it on a smooth white sheet of plastic for Tim to photograph. It wasn’t “punk “–it was smooth-skinned. They assumed that, much to her dismay, she must have picked up the wrong frog.

“I then put the frog back in the cup and added some moss,” she said. “The spines came back… we simply couldn’t believe our eyes, our frog changed skin texture!

“I put the frog back on the smooth white background. Its skin became smooth.”

“The spines and coloration help them blend into mossy habitats, making it hard for us to see them,” she said. “But whether the texture really helps them elude predators still needs to be tested.”

During the next three years, a team of fellow biologists studied the frogs. They found the animals shift skin texture in a little more than three minutes.

Juan M. Guayasamin, from Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Ecuador, the manuscript’s first author, performed morphological and genetic analyses showing that P. mutabilis was a unique and undescribed species. Carl R. Hutter, from the University of Kansas, studied the frog’s calls, finding three songs the species uses, which differentiate them from relatives. The fifth author of the paper, Jamie Culebras, assisted with fieldwork and was able to locate a second population of the species. Culebras is a member of Tropical Herping, an organization committed to discovering, and studying reptiles and amphibians.

Guayasamin and Hutter discovered that Prismantis sobetes, a relative with similar markings but about twice the size of P. mutabilis, has the same trait when they placed a spiny specimen on a sheet and watched its skin turn smooth. P. sobetes is the only relative that has been tested so far.

Because the appearance of animals has long been one of the keys to identifying them as a certain species, the researchers believe their find challenges the system, particularly for species identified by one or just a few preserved specimens. With those, there was and is no way to know if the appearance is changeable.

The Krynaks, who helped form Las Gralarias Foundation to support the conservation efforts of the reserve, plan to return to continue surveying for mutable rain frogs and to work with fellow researchers to further document their behaviors, lifecycle and texture shifting, and estimate their population, all in effort to improve our knowledge and subsequent ability to conserve this paradigm shifting species.

Further, they hope to discern whether more relatives have the ability to shift skin texture and if that trait comes from a common ancestor. If P. mutabilis and P. sobetes are the only species within this branch of Pristimantis frogs to have this capability, they hope to learn whether they retained it from an ancestor while relatives did not, or whether the trait evolved independently in each species.

Golden frog of Panama and its skin microbiome

Caption: Researchers studied microbial communities on the skin of Panamanian golden frogs to learn more about amphibian disease resistance. Panamanian golden frogs live only in captivity. Continued studies may help restore them back to the wild.

Credit: B. Gratwicke/Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute

Among many of the pressures on frog populations, there’s a lethal fungus which has affected some 200 species of frogs. A March 23, 2015 news item on ScienceDaily describes some recent research into the bacterial communities present on frog skin,

A team of scientists including Virginia Tech researchers is one step closer to understanding how bacteria on a frog’s skin affects its likelihood of contracting disease.

A frog-killing fungus known as Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, or Bd, has already led to the decline of more than 200 amphibian species including the now extinct-in-the-wild Panamanian golden frog.

In a recent study, the research team attempted to apply beneficial bacteria found on the skin of various Bd-resistant wild Panamanian frog species to Panamanian golden frogs in captivity, to see if this would stimulate a defense against the disease.

A March 23, 2015 Virginia Tech University news release on EurekAlert, which originated the news item, provides a twist and a turn in the story (Note: Links have been removed),

They found that while the treatment with beneficial bacteria was not successful due to its inability to stick to the skin, there were some frogs that survived exposure to the fungus.

These survivors actually had unique bacterial communities on their skin before the experiments started.

…

The next step is to explore these new bacterial communities.

“We were disappointed that the treatment didn’t work, but glad to have discovered new information about the relationship between these symbiotic microbial communities and amphibian disease resistance,” said Lisa Belden, an associate professor of biological sciences in the College of Science, a Fralin Life Science Institute affiliate, and a faculty member with the new Global Change Center at Virginia Tech. “Every bit of information gets us closer to getting these frogs back into nature.”

Studying the microbial communities of Panamanian golden frogs was the dissertation focus of Belden’s former graduate student Matthew Becker, who graduated with a Ph.D. in biological sciences from Virginia Tech in 2014 and is now a fellow at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute.

“Anything that can help us predict resistance to this disease is very useful because the ultimate goal of this research is to establish healthy populations of golden frogs in their native habitat,” Becker told Smithsonian Science News. “I think identifying alternative probiotic treatment methods that optimize dosages and exposure times will be key for moving forward with the use of probiotics to mitigate chytridiomycosis.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Composition of symbiotic bacteria predicts survival in Panamanian golden frogs infected with a lethal fungus by Matthew H. Becker , Jenifer B. Walke , Shawna Cikanek , Anna E. Savage , Nichole Mattheus , Celina N. Santiago , Kevin P. C. Minbiole , Reid N. Harris , Lisa K. Belden , Brian Gratwicke. April 2015 Volume: 282 Issue: 1805 DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2014.2881 Published 18 March 2015

This is an open access paper.

For anyone curious about the article in the Smithsonian mentioned in the news release, you can find it here.