There are high hopes (more about why later) for a plant-based ‘flamenco dancing molecule’ and its inclusion in sunscreens as described in an October 18, 2019 University of Warwick press release (also on EurekAlert),

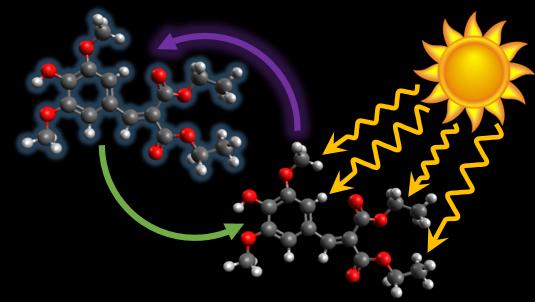

A molecule that protects plants from overexposure to harmful sunlight thanks to its flamenco-style twist could form the basis for a new longer-lasting sunscreen, chemists at the University of Warwick have found, in collaboration with colleagues in France and Spain. Research on the green molecule by the scientists has revealed that it absorbs ultraviolet light and then disperses it in a ‘flamenco-style’ dance, making it ideal for use as a UV filter in sunscreens.

The team of scientists report today, Friday 18th October 2019, in the journal Nature Communications that, as well as being plant-inspired, this molecule is also among a small number of suitable substances that are effective in absorbing light in the Ultraviolet A (UVA) region of wavelengths. It opens up the possibility of developing a naturally-derived and eco-friendly sunscreen that protects against the full range of harmful wavelengths of light from the sun.

The UV filters in a sunscreen are the ingredients that predominantly provide the protection from the sun’s rays. In addition to UV filters, sunscreens will typically also include:

Emollients, used for moisturising and lubricating the skin

Thickening agents

Emulsifiers to bind all the ingredients

Water

Other components that improve aesthetics, water resistance, etc.

The researchers tested a molecule called diethyl sinapate, a close mimic to a molecule that is commonly found in the leaves of plants, which is responsible for protecting them from overexposure to UV light while they absorb visible light for photosynthesis.They first exposed the molecule to a number of different solvents to determine whether that had any impact on its (principally) light absorbing behaviour. They then deposited a sample of the molecule on an industry standard human skin mimic (VITRO-CORNEUM®) where it was irradiated with different wavelengths of UV light. They used the state-of-the-art laser facilities within the Warwick Centre for Ultrafast Spectroscopy to take images of the molecule at extremely high speeds, to observe what happens to the light’s energy when it’s absorbed in the molecule in the very early stages (millionths of millionths of a second). Other techniques were also used to establish longer term (many hours) properties of diethyl sinapate, such as endocrine disruption activity and antioxidant potential.

Professor Vasilios Stavros from the University of Warwick, Department of Chemistry, who was part of the research team, explains: “A really good sunscreen absorbs light and converts it to harmless heat. A bad sunscreen is one that absorbs light and then, for example, breaks down potentially inducing other chemistry that you don’t want. Diethyl sinapate generates lots of heat, and that’s really crucial.”

When irradiated the molecule absorbs light and goes into an excited state but that energy then has to be disposed of somehow. The team of researchers observed that it does a kind of molecular ‘dance’ a mere 10 picoseconds (ten millionths of a millionth of a second) long: a twist in a similar fashion to the filigranas and floreos hand movements of flamenco dancers. That causes it to come back to its original ground state and convert that energy into vibrational energy, or heat.

It is this ‘flamenco dance’ that gives the molecule its long-lasting qualities. When the scientists bombarded the molecule with UVA light they found that it degraded only 3% over two hours, compared to the industry requirement of 30%.

Dr Michael Horbury, who was a Postgraduate Research Fellow at The University Warwick when he undertook this research (and now at the University of Leeds) adds: “We have shown that by studying the molecular dance on such a short time-scale, the information that you gain can have tremendous repercussions on how you design future sunscreens.

Emily Holt, a PhD student in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Warwick who was part of the research team, said: “The next step would be to test it on human skin, then to mix it with other ingredients that you find in a sunscreen to see how those affect its characteristics.”Professor Florent Allais and Dr Louis Mouterde, URD Agro-Biotechnologies Industrielles at AgroParisTech (Pomacle, France) commented: “What we have developed together is a molecule based upon a UV photoprotective molecule found in the surface of leaves on a plant and refunctionalised it using greener synthetic procedures. Indeed, this molecule has excellent long-term properties while exhibiting low endocrine disruption and valuable antioxidant properties.”

Professor Laurent Blasco, Global Technical Manager (Skin Essentials) at Lubrizol and Honorary Professor at the University of Warwick commented: “In sunscreen formulations at the moment there is a lack of broad-spectrum protection from a single UV filter. Our collaboration has gone some way towards developing a next generation broad-spectrum UV filter inspired by nature. Our collaboration has also highlighted the importance of academia and industry working together towards a common goal.”

Professor Vasilios Stavros added, “Amidst escalating concerns about their impact on human toxicity (e.g. endocrine disruption) and ecotoxicity (e.g. coral bleaching), developing new UV filters is essential. We have demonstrated that a highly attractive avenue is ‘nature-inspired’ UV filters, which provide a front-line defence against skin cancer and premature skin aging.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Towards symmetry driven and nature inspired UV filter design by Michael D. Horbury, Emily L. Holt, Louis M. M. Mouterde, Patrick Balaguer, Juan Cebrián, Laurent Blasco, Florent Allais & Vasilios G. Stavros. Nature Communications volume 10, Article number: 4748 (2019) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12719-z

This paper is open access.

Why the high hopes?

Briefly (the long story stretches over 10 years), the most recommended sunscreens today (2020) are ‘mineral-based’. This is painfully amusing because civil society groups (activists) such as Friends of the Earth (in particular the Australia chapter under Georgia Miller’s leadership) and Canada’s own ETC Group had campaigned against these same sunscreen when they were billed as being based on metal oxide nanoparticles such zinc oxide and/or titanium oxide. The ETC Group under Pat Roy Mooney’s leadership didn’t press the campaign after an initial push. As for Australia and Friend of the Earth, their anti-metallic oxide nanoparticle sunscreen campaign didn’t work out well as I noted in a February 9, 2012 posting and with a follow-up in an October 31, 2012 posting.

The only civil society group to give approval (very reluctantly) was the Environmental Working Group (EWG) as I noted in a July 9, 2009 posting. They had concerns about the fact that these ingredients are metallic but after a thorough of then available research, EWG gave the sunscreens a passing grade and noted, in their report, that they had more concerns about the use of oxybenzone in sunscreens. That latter concern has since been flagged by others (e.g., the state of Hawai’i) as noted in my July 6, 2018 posting.

So, rebranding metallic oxides as minerals has allowed the various civil society groups to support the very same sunscreens many of them were advocating against.

In the meantime, scientists continue work on developing plant-based sunscreens as an improvement to the ‘mineral-based’ sunscreens used now.