For the first time in the 15 years this blog has been around, the Nobel prizes awarded in medicine, physics, and chemistry all are in areas discussed here at one or another. As usual where people are concerned, some of these scientists had a tortuous journey to this prestigious outcome.

Medicine

Two people (Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman) were awarded the prize in medicine according to the October 2, 2023 Nobel Prize press release, Note: Links have been removed,

The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet [Sweden]

has today decided to award

the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

jointly to

Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman

for their discoveries concerning nucleoside base modifications that enabled the development of effective mRNA vaccines against COVID-19

The discoveries by the two Nobel Laureates were critical for developing effective mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 during the pandemic that began in early 2020. Through their groundbreaking findings, which have fundamentally changed our understanding of how mRNA interacts with our immune system, the laureates contributed to the unprecedented rate of vaccine development during one of the greatest threats to human health in modern times.

Vaccines before the pandemic

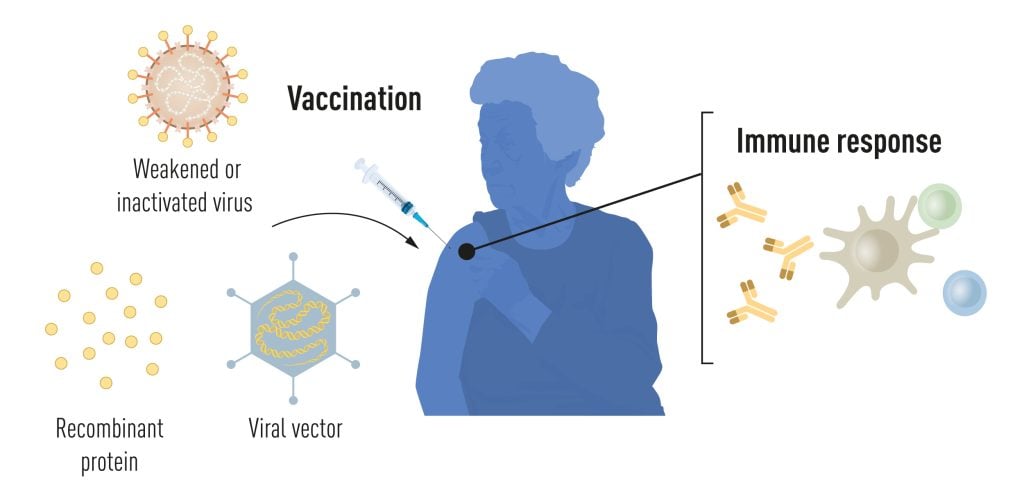

Vaccination stimulates the formation of an immune response to a particular pathogen. This gives the body a head start in the fight against disease in the event of a later exposure. Vaccines based on killed or weakened viruses have long been available, exemplified by the vaccines against polio, measles, and yellow fever. In 1951, Max Theiler was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for developing the yellow fever vaccine.

Thanks to the progress in molecular biology in recent decades, vaccines based on individual viral components, rather than whole viruses, have been developed. Parts of the viral genetic code, usually encoding proteins found on the virus surface, are used to make proteins that stimulate the formation of virus-blocking antibodies. Examples are the vaccines against the hepatitis B virus and human papillomavirus. Alternatively, parts of the viral genetic code can be moved to a harmless carrier virus, a “vector.” This method is used in vaccines against the Ebola virus. When vector vaccines are injected, the selected viral protein is produced in our cells, stimulating an immune response against the targeted virus.

Producing whole virus-, protein- and vector-based vaccines requires large-scale cell culture. This resource-intensive process limits the possibilities for rapid vaccine production in response to outbreaks and pandemics. Therefore, researchers have long attempted to develop vaccine technologies independent of cell culture, but this proved challenging.

mRNA vaccines: A promising idea

In our cells, genetic information encoded in DNA is transferred to messenger RNA (mRNA), which is used as a template for protein production. During the 1980s, efficient methods for producing mRNA without cell culture were introduced, called in vitro transcription. This decisive step accelerated the development of molecular biology applications in several fields. Ideas of using mRNA technologies for vaccine and therapeutic purposes also took off, but roadblocks lay ahead. In vitro transcribed mRNA was considered unstable and challenging to deliver, requiring the development of sophisticated carrier lipid systems to encapsulate the mRNA. Moreover, in vitro-produced mRNA gave rise to inflammatory reactions. Enthusiasm for developing the mRNA technology for clinical purposes was, therefore, initially limited.

These obstacles did not discourage the Hungarian biochemist Katalin Karikó, who was devoted to developing methods to use mRNA for therapy. During the early 1990s, when she was an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania, she remained true to her vision of realizing mRNA as a therapeutic despite encountering difficulties in convincing research funders of the significance of her project. A new colleague of Karikó at her university was the immunologist Drew Weissman. He was interested in dendritic cells, which have important functions in immune surveillance and the activation of vaccine-induced immune responses. Spurred by new ideas, a fruitful collaboration between the two soon began, focusing on how different RNA types interact with the immune system.

The breakthrough

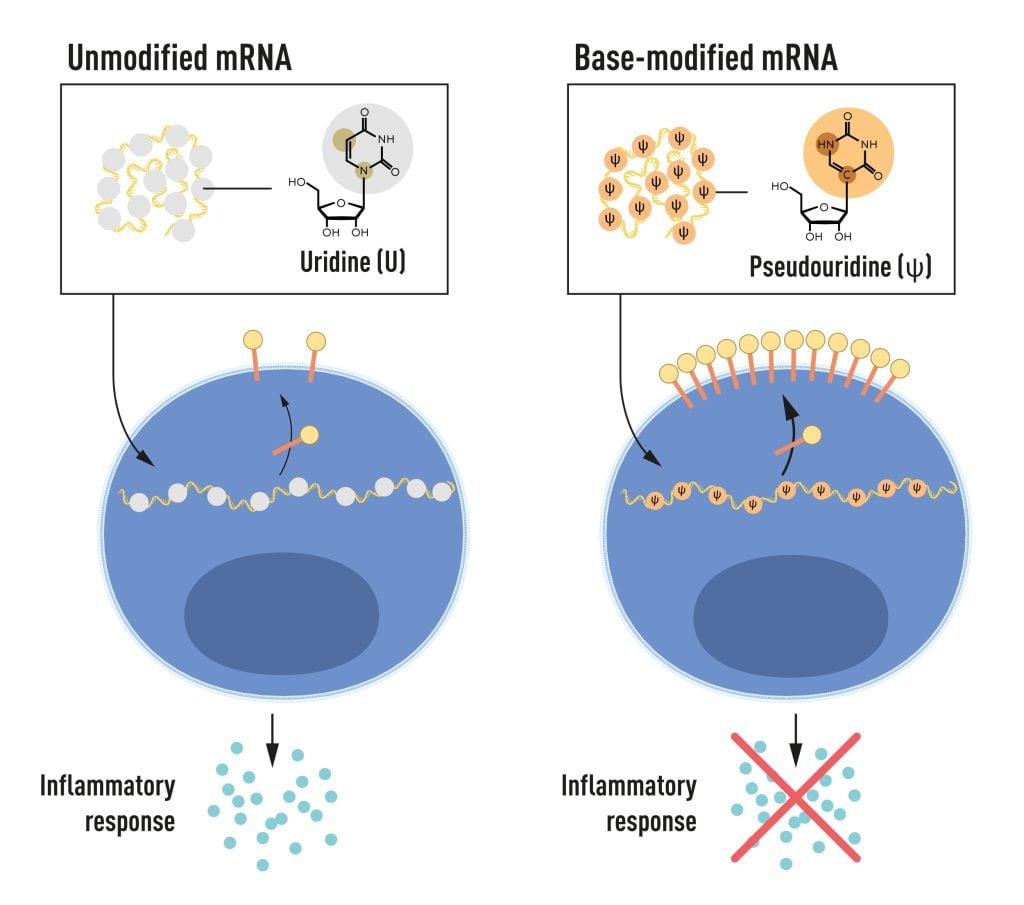

Karikó and Weissman noticed that dendritic cells recognize in vitro transcribed mRNA as a foreign substance, which leads to their activation and the release of inflammatory signaling molecules. They wondered why the in vitro transcribed mRNA was recognized as foreign while mRNA from mammalian cells did not give rise to the same reaction. Karikó and Weissman realized that some critical properties must distinguish the different types of mRNA.

RNA contains four bases, abbreviated A, U, G, and C, corresponding to A, T, G, and C in DNA, the letters of the genetic code. Karikó and Weissman knew that bases in RNA from mammalian cells are frequently chemically modified, while in vitro transcribed mRNA is not. They wondered if the absence of altered bases in the in vitro transcribed RNA could explain the unwanted inflammatory reaction. To investigate this, they produced different variants of mRNA, each with unique chemical alterations in their bases, which they delivered to dendritic cells. The results were striking: The inflammatory response was almost abolished when base modifications were included in the mRNA. This was a paradigm change in our understanding of how cells recognize and respond to different forms of mRNA. Karikó and Weissman immediately understood that their discovery had profound significance for using mRNA as therapy. These seminal results were published in 2005, fifteen years before the COVID-19 pandemic.

In further studies published in 2008 and 2010, Karikó and Weissman showed that the delivery of mRNA generated with base modifications markedly increased protein production compared to unmodified mRNA. The effect was due to the reduced activation of an enzyme that regulates protein production. Through their discoveries that base modifications both reduced inflammatory responses and increased protein production, Karikó and Weissman had eliminated critical obstacles on the way to clinical applications of mRNA.

mRNA vaccines realized their potential

Interest in mRNA technology began to pick up, and in 2010, several companies were working on developing the method. Vaccines against Zika virus and MERS-CoV were pursued; the latter is closely related to SARS-CoV-2. After the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, two base-modified mRNA vaccines encoding the SARS-CoV-2 surface protein were developed at record speed. Protective effects of around 95% were reported, and both vaccines were approved as early as December 2020.

The impressive flexibility and speed with which mRNA vaccines can be developed pave the way for using the new platform also for vaccines against other infectious diseases. In the future, the technology may also be used to deliver therapeutic proteins and treat some cancer types.

Several other vaccines against SARS-CoV-2, based on different methodologies, were also rapidly introduced, and together, more than 13 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses have been given globally. The vaccines have saved millions of lives and prevented severe disease in many more, allowing societies to open and return to normal conditions. Through their fundamental discoveries of the importance of base modifications in mRNA, this year’s Nobel laureates critically contributed to this transformative development during one of the biggest health crises of our time.

…

Read more about this year’s prize

Katalin Karikó was born in 1955 in Szolnok, Hungary. She received her PhD from Szeged’s University in 1982 and performed postdoctoral research at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Szeged until 1985. She then conducted postdoctoral research at Temple University, Philadelphia, and the University of Health Science, Bethesda. In 1989, she was appointed Assistant Professor at the University of Pennsylvania, where she remained until 2013. After that, she became vice president and later senior vice president at BioNTech RNA Pharmaceuticals. Since 2021, she has been a Professor at Szeged University and an Adjunct Professor at Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

Drew Weissman was born in 1959 in Lexington, Massachusetts, USA. He received his MD, PhD degrees from Boston University in 1987. He did his clinical training at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center at Harvard Medical School and postdoctoral research at the National Institutes of Health. In 1997, Weissman established his research group at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the Roberts Family Professor in Vaccine Research and Director of the Penn Institute for RNA Innovations.

The University of Pennsylvania October 2, 2023 news release is a very interesting announcement (more about why it’s interesting afterwards), Note: Links have been removed,

The University of Pennsylvania messenger RNA pioneers whose years of scientific partnership unlocked understanding of how to modify mRNA to make it an effective therapeutic—enabling a platform used to rapidly develop lifesaving vaccines amid the global COVID-19 pandemic—have been named winners of the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. They become the 28th and 29th Nobel laureates affiliated with Penn, and join nine previous Nobel laureates with ties to the University of Pennsylvania who have won the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

Nearly three years after the rollout of mRNA vaccines across the world, Katalin Karikó, PhD, an adjunct professor of Neurosurgery in Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine, and Drew Weissman, MD, PhD, the Roberts Family Professor of Vaccine Research in the Perelman School of Medicine, are recipients of the prize announced this morning by the Nobel Assembly in Solna, Sweden.

After a chance meeting in the late 1990s while photocopying research papers, Karikó and Weissman began investigating mRNA as a potential therapeutic. In 2005, they published a key discovery: mRNA could be altered and delivered effectively into the body to activate the body’s protective immune system. The mRNA-based vaccines elicited a robust immune response, including high levels of antibodies that attack a specific infectious disease that has not previously been encountered. Unlike other vaccines, a live or attenuated virus is not injected or required at any point.

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, the true value of the pair’s lab work was revealed in the most timely of ways, as companies worked to quickly develop and deploy vaccines to protect people from the virus. Both Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna utilized Karikó and Weissman’s technology to build their highly effective vaccines to protect against severe illness and death from the virus. In the United States alone, mRNA vaccines make up more than 655 million total doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines that have been administered since they became available in December 2020.

…

Editor’s Note: The Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 mRNA vaccines both use licensed University of Pennsylvania technology. As a result of these licensing relationships, Penn, Karikó and Weissman have received and may continue to receive significant financial benefits in the future based on the sale of these products. BioNTech provides funding for Weissman’s research into the development of additional infectious disease vaccines.

Science can be brutal

Now for the interesting bit: it’s in my March 5, 2021 posting (mRNA, COVID-19 vaccines, treating genetic diseases before birth, and the scientist who started it all),

…

Before messenger RNA was a multibillion-dollar idea, it was a scientific backwater. And for the Hungarian-born scientist behind a key mRNA discovery, it was a career dead-end.

Katalin Karikó spent the 1990s collecting rejections. Her work, attempting to harness the power of mRNA to fight disease, was too far-fetched for government grants, corporate funding, and even support from her own colleagues.

…

“Every night I was working: grant, grant, grant,” Karikó remembered, referring to her efforts to obtain funding. “And it came back always no, no, no.”

By 1995, after six years on the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania, Karikó got demoted. [emphasis mine] She had been on the path to full professorship, but with no money coming in to support her work on mRNA, her bosses saw no point in pressing on.

She was back to the lower rungs of the scientific academy.

“Usually, at that point, people just say goodbye and leave because it’s so horrible,” Karikó said.

There’s no opportune time for demotion, but 1995 had already been uncommonly difficult. Karikó had recently endured a cancer scare, and her husband was stuck in Hungary sorting out a visa issue. Now the work to which she’d devoted countless hours was slipping through her fingers.

…

In time, those better experiments came together. After a decade of trial and error, Karikó and her longtime collaborator at Penn — Drew Weissman [emphasis mine], an immunologist with a medical degree and Ph.D. from Boston University — discovered a remedy for mRNA’s Achilles’ heel.

…

You can get the whole story from my March 5, 2021 posting, scroll down to the “mRNA—it’s in the details, plus, the loneliness of pioneer researchers, a demotion, and squabbles” subhead. If you are very curious about mRNA and the rough and tumble of the world of science, there’s my August 20, 2021 posting “Getting erased from the mRNA/COVID-19 story” where Ian MacLachlan is featured as a researcher who got erased and where Karikó credits his work.

‘Rowing Mom Wins Nobel’ (credit: rowing website Row 2K)

Karikó’s daughter is a two-time gold medal Olympic athlete as the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s (CBC) radio programme, As It Happens, notes in an interview with the daughter (Susan Francia). From an October 4, 2023 As It Happens article (with embedded audio programme excerpt) by Sheena Goodyear,

Olympic gold medallist Susan Francia is coming to terms with the fact that she’s no longer the most famous person in her family.

That’s because the retired U.S. rower’s mother, Katalin Karikó, just won a Nobel Prize in Medicine. The biochemist was awarded alongside her colleague, vaccine researcher Drew Weissman, for their groundbreaking work that led to the development of COVID-19 vaccines.

“Now I’m like, ‘Shoot! All right, I’ve got to work harder,'” Francia said with a laugh during an interview with As It Happens host Nil Köksal.

But in all seriousness, Francia says she’s immensely proud of her mother’s accomplishments. In fact, it was Karikó’s fierce dedication to science that inspired Francia to win Olympic gold medals in 2008 and 2012.

“Sport is a lot like science in that, you know, you have a passion for something and you just go and you train, attain your goal, whether it be making this discovery that you truly believe in, or for me, it was trying to be the best in the world,” Francia said.

“It’s a grind and, honestly, I love that grind. And my mother did too.”

…

… one of her [Karikó] favourite headlines so far comes from a little blurb on the rowing website Row 2K: “Rowing Mom Wins Nobel.”

…

Nowadays, scientists are trying to harness the power of mRNA to fight cancer, malaria, influenza and rabies. But when Karikó first began her work, it was a fringe concept. For decades, she toiled in relative obscurity, struggling to secure funding for her research.

“That’s also that same passion that I took into my rowing,” Francia said.

But even as Karikó struggled to make a name for herself, she says her own mother, Zsuzsanna, always believed she would earn a Nobel Prize one day.

Every year, as the Nobel Prize announcement approached, she would tell Karikó she’d be watching for her name.

“I was laughing [and saying] that, ‘Mom, I am not getting anything,'” she said.

But her mother, who died a few years ago, ultimately proved correct.

…

Congratulations to both Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman and thank you both for persisting!

Physics

This prize is for physics at the attoscale.

Aaron W. Harrison (Assistant Professor of Chemistry, Austin College, Texas, US) attempts an explanation of an attosecond in his October 3, 2023 essay (in English “What is an attosecond? A physical chemist explains the tiny time scale behind Nobel Prize-winning research” and in French “Nobel de physique : qu’est-ce qu’une attoseconde?”) for The Conversation, Note: Links have been removed,

…

“Atto” is the scientific notation prefix that represents 10-18, which is a decimal point followed by 17 zeroes and a 1. So a flash of light lasting an attosecond, or 0.000000000000000001 of a second, is an extremely short pulse of light.

In fact, there are approximately as many attoseconds in one second as there are seconds in the age of the universe.

Previously, scientists could study the motion of heavier and slower-moving atomic nuclei with femtosecond (10-15) light pulses. One thousand attoseconds are in 1 femtosecond. But researchers couldn’t see movement on the electron scale until they could generate attosecond light pulses – electrons move too fast for scientists to parse exactly what they are up to at the femtosecond level.

…

Harrison does a very good job of explaining something that requires a leap of imagination. He also explains why scientists engage in attosecond research. h/t October 4, 2023 news item on phys.org

Amelle Zaïr (Imperial College London) offers a more technical explanation in her October 4, 2023 essay about the 2023 prize winners for The Conversation. h/t October 4, 2023 news item on phys.org

Main event

Here’s the October 3, 2023 Nobel Prize press release, Note: A link has been removed,

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the Nobel Prize in Physics 2023 to

Pierre Agostini

The Ohio State University, Columbus, USAFerenc Krausz

Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics, Garching and Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, GermanyAnne L’Huillier

Lund University, Sweden“for experimental methods that generate attosecond pulses of light for the study of electron dynamics in matter”

Experiments with light capture the shortest of moments

The three Nobel Laureates in Physics 2023 are being recognised for their experiments, which have given humanity new tools for exploring the world of electrons inside atoms and molecules. Pierre Agostini, Ferenc Krausz and Anne L’Huillier have demonstrated a way to create extremely short pulses of light that can be used to measure the rapid processes in which electrons move or change energy.

Fast-moving events flow into each other when perceived by humans, just like a film that consists of still images is perceived as continual movement. If we want to investigate really brief events, we need special technology. In the world of electrons, changes occur in a few tenths of an attosecond – an attosecond is so short that there are as many in one second as there have been seconds since the birth of the universe.

The laureates’ experiments have produced pulses of light so short that they are measured in attoseconds, thus demonstrating that these pulses can be used to provide images of processes inside atoms and molecules.

In 1987, Anne L’Huillier discovered that many different overtones of light arose when she transmitted infrared laser light through a noble gas. Each overtone is a light wave with a given number of cycles for each cycle in the laser light. They are caused by the laser light interacting with atoms in the gas; it gives some electrons extra energy that is then emitted as light. Anne L’Huillier has continued to explore this phenomenon, laying the ground for subsequent breakthroughs.

In 2001, Pierre Agostini succeeded in producing and investigating a series of consecutive light pulses, in which each pulse lasted just 250 attoseconds. At the same time, Ferenc Krausz was working with another type of experiment, one that made it possible to isolate a single light pulse that lasted 650 attoseconds.

The laureates’ contributions have enabled the investigation of processes that are so rapid they were previously impossible to follow.

“We can now open the door to the world of electrons. Attosecond physics gives us the opportunity to understand mechanisms that are governed by electrons. The next step will be utilising them,” says Eva Olsson, Chair of the Nobel Committee for Physics.

There are potential applications in many different areas. In electronics, for example, it is important to understand and control how electrons behave in a material. Attosecond pulses can also be used to identify different molecules, such as in medical diagnostics.

…

Read more about this year’s prize

Popular science background: Electrons in pulses of light (pdf)

Scientific background: “For experimental methods that generate attosecond pulses of light for the study of electron dynamics in matter” (pdf)Pierre Agostini. PhD 1968 from Aix-Marseille University, France. Professor at The Ohio State University, Columbus, USA.

Ferenc Krausz, born 1962 in Mór, Hungary. PhD 1991 from Vienna University of Technology, Austria. Director at Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics, Garching and Professor at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany.

Anne L’Huillier, born 1958 in Paris, France. PhD 1986 from University Pierre and Marie Curie, Paris, France. Professor at Lund University, Sweden.

A Canadian connection?

An October 3, 2023 CBC online news item from the Associated Press reveals a Canadian connection of sorts ,

Three scientists have won the Nobel Prize in physics Tuesday for giving us the first split-second glimpse into the superfast world of spinning electrons, a field that could one day lead to better electronics or disease diagnoses.

The award went to French-Swedish physicist Anne L’Huillier, French scientist Pierre Agostini and Hungarian-born Ferenc Krausz for their work with the tiny part of each atom that races around the centre, and that is fundamental to virtually everything: chemistry, physics, our bodies and our gadgets.

Electrons move around so fast that they have been out of reach of human efforts to isolate them. But by looking at the tiniest fraction of a second possible, scientists now have a “blurry” glimpse of them, and that opens up whole new sciences, experts said.

“The electrons are very fast, and the electrons are really the workforce in everywhere,” Nobel Committee member Mats Larsson said. “Once you can control and understand electrons, you have taken a very big step forward.”

L’Huillier is the fifth woman to receive a Nobel in Physics.

…

L’Huillier was teaching basic engineering physics to about 100 undergraduates at Lund when she got the call that she had won, but her phone was on silent and she didn’t pick up. She checked it during a break and called the Nobel Committee.

Then she went back to teaching.

…

Agostini, an emeritus professor at Ohio State University, was in Paris and could not be reached by the Nobel Committee before it announced his win to the world

…

Here’s the Canadian connection (from the October 3, 2023 CBC online news item),

…

Krausz, of the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics and Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, told reporters that he was bewildered.

“I have been trying to figure out since 11 a.m. whether I’m in reality or it’s just a long dream,” the 61-year-old said.

Last year, Krausz and L’Huillier won the prestigious Wolf prize in physics for their work, sharing it with University of Ottawa scientist Paul Corkum [emphasis mine]. Nobel prizes are limited to only three winners and Krausz said it was a shame that it could not include Corkum.

Corkum was key to how the split-second laser flashes could be measured [emphasis mine], which was crucial, Krausz said.

…

Congratulations to Pierre Agostini, Ferenc Krausz and Anne L’Huillier and a bow to Paul Corkum!

For those who are curious. a ‘Paul Corkum’ search should bring up a few postings on this blog but I missed this piece of news, a May 4, 2023 University of Ottawa news release about Corkum and the 2022 Wolf Prize, which he shared with Krausz and L’Huillier,

Chemistry

There was a little drama where this prize was concerned, It was announced too early according to an October 4, 2023 news item on phys.org and, again, in another October 4, 2023 news item on phys.org (from the Oct. 4, 2023 news item by Karl Ritter for the Associated Press),

Oops! Nobel chemistry winners are announced early in a rare slip-up

The most prestigious and secretive prize in science ran headfirst into the digital era Wednesday when Swedish media got an emailed press release revealing the winners of the Nobel Prize in chemistry and the news prematurely went public.

…

Here’s the fully sanctioned October 4, 2023 Nobel Prize press release, Note: A link has been removed,

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2023 to

Moungi G. Bawendi

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, MA, USALouis E. Brus

Columbia University, New York, NY, USAAlexei I. Ekimov

Nanocrystals Technology Inc., New York, NY, USA“for the discovery and synthesis of quantum dots”

They planted an important seed for nanotechnology

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2023 rewards the discovery and development of quantum dots, nanoparticles so tiny that their size determines their properties. These smallest components of nanotechnology now spread their light from televisions and LED lamps, and can also guide surgeons when they remove tumour tissue, among many other things.

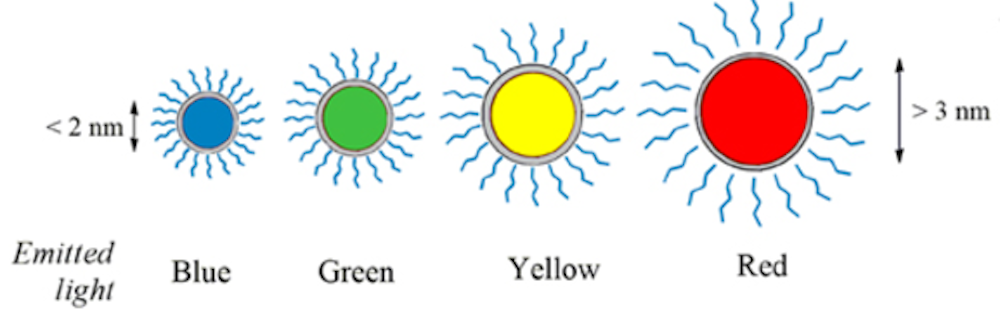

Everyone who studies chemistry learns that an element’s properties are governed by how many electrons it has. However, when matter shrinks to nano-dimensions quantum phenomena arise; these are governed by the size of the matter. The Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 2023 have succeeded in producing particles so small that their properties are determined by quantum phenomena. The particles, which are called quantum dots, are now of great importance in nanotechnology.

“Quantum dots have many fascinating and unusual properties. Importantly, they have different colours depending on their size,” says Johan Åqvist, Chair of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry.

Physicists had long known that in theory size-dependent quantum effects could arise in nanoparticles, but at that time it was almost impossible to sculpt in nanodimensions. Therefore, few people believed that this knowledge would be put to practical use.

However, in the early 1980s, Alexei Ekimov succeeded in creating size-dependent quantum effects in coloured glass. The colour came from nanoparticles of copper chloride and Ekimov demonstrated that the particle size affected the colour of the glass via quantum effects.

A few years later, Louis Brus was the first scientist in the world to prove size-dependent quantum effects in particles floating freely in a fluid.

In 1993, Moungi Bawendi revolutionised the chemical production of quantum dots, resulting in almost perfect particles. This high quality was necessary for them to be utilised in applications.

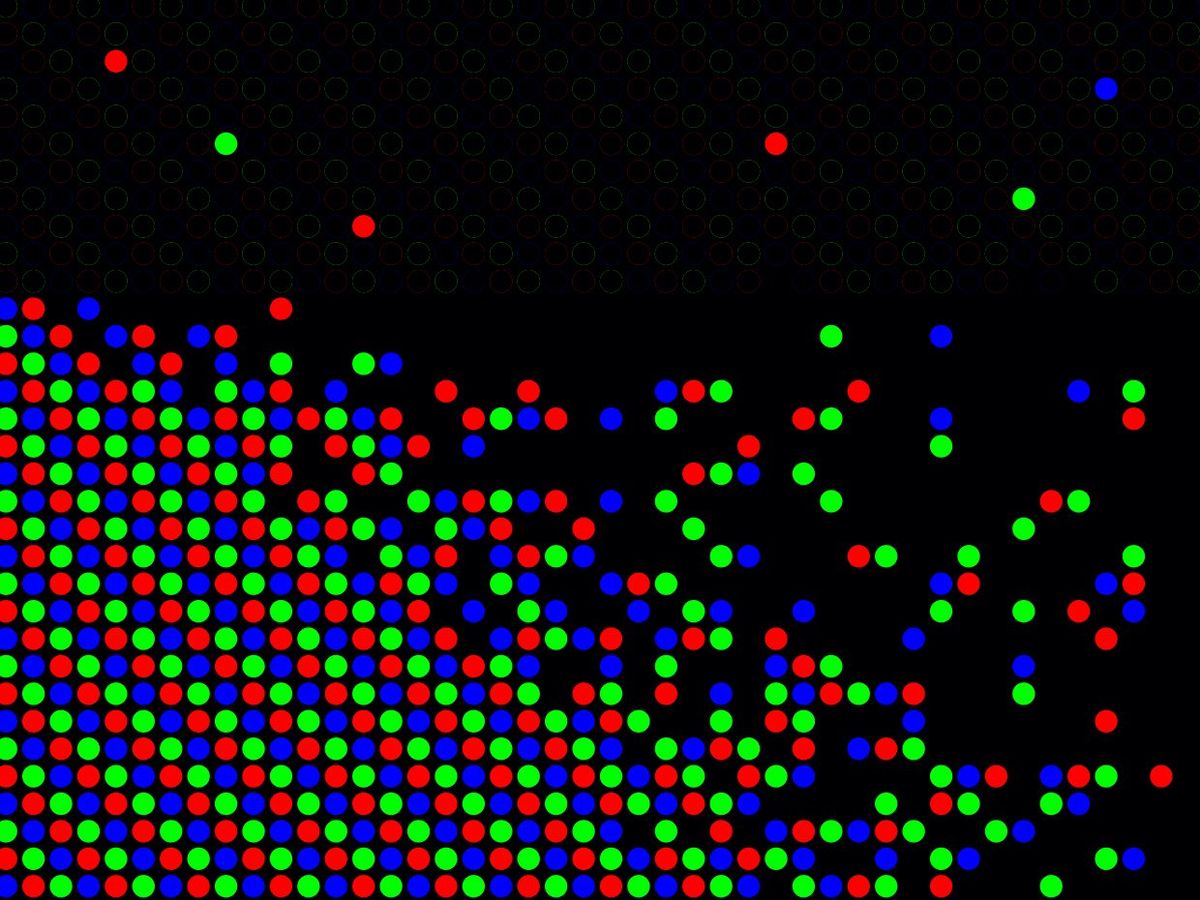

Quantum dots now illuminate computer monitors and television screens based on QLED technology. They also add nuance to the light of some LED lamps, and biochemists and doctors use them to map biological tissue.

Quantum dots are thus bringing the greatest benefit to humankind. Researchers believe that in the future they could contribute to flexible electronics, tiny sensors, thinner solar cells and encrypted quantum communication – so we have just started exploring the potential of these tiny particles.

…

Read more about this year’s prize

Popular science background: They added colour to nanotechnology (pdf)

Scientific background: Quantum dots – seeds of nanoscience (pdf)Moungi G. Bawendi, born 1961 in Paris, France. PhD 1988 from University of Chicago, IL, USA. Professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, MA, USA.

Louis E. Brus, born 1943 in Cleveland, OH, USA. PhD 1969 from Columbia University, New York, NY, USA. Professor at Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

Alexei I. Ekimov, born 1945 in the former USSR. PhD 1974 from Ioffe Physical-Technical Institute, Saint Petersburg, Russia. Formerly Chief Scientist at Nanocrystals Technology Inc., New York, NY, USA.

The most recent ‘quantum dot’ (a particular type of nanoparticle) story here is a January 5, 2023 posting, “Can I have a beer with those carbon quantum dots?“

Proving yet again that scientists can have a bumpy trip to a Nobel prize, an October 4, 2023 news item on phys.org describes how one of the winners flunked his first undergraduate chemistry test, Note: Links have been removed,

Talk about bouncing back. MIT professor Moungi Bawendi is a co-winner of this year’s Nobel chemistry prize for helping develop “quantum dots”—nanoparticles that are now found in next generation TV screens and help illuminate tumors within the body.

But as an undergraduate, he flunked his very first chemistry exam, recalling that the experience nearly “destroyed” him.

The 62-year-old of Tunisian and French heritage excelled at science throughout high school, without ever having to break a sweat.

But when he arrived at Harvard University as an undergraduate in the late 1970s, he was in for a rude awakening.

…

You can find more about the winners and quantum dots in an October 4, 2023 news item on Nanowerk and in Dr. Andrew Maynard’s (Professor of Advanced Technology Transitions, Arizona State University) October 4, 2023 essay for The Conversation (h/t October 4, 2023 news item on phys.org), Note: Links have been removed,

…

This year’s prize recognizes Moungi Bawendi, Louis Brus and Alexei Ekimov for the discovery and development of quantum dots. For many years, these precisely constructed nanometer-sized particles – just a few hundred thousandths the width of a human hair in diameter – were the darlings of nanotechnology pitches and presentations. As a researcher and adviser on nanotechnology [emphasis mine], I’ve [Dr. Andrew Maynard] even used them myself when talking with developers, policymakers, advocacy groups and others about the promise and perils of the technology.

The origins of nanotechnology predate Bawendi, Brus and Ekimov’s work on quantum dots – the physicist Richard Feynman speculated on what could be possible through nanoscale engineering as early as 1959, and engineers like Erik Drexler were speculating about the possibilities of atomically precise manufacturing in the the 1980s. However, this year’s trio of Nobel laureates were part of the earliest wave of modern nanotechnology where researchers began putting breakthroughs in material science to practical use.

Quantum dots brilliantly fluoresce: They absorb one color of light and reemit it nearly instantaneously as another color. A vial of quantum dots, when illuminated with broad spectrum light, shines with a single vivid color. What makes them special, though, is that their color is determined by how large or small they are. Make them small and you get an intense blue. Make them larger, though still nanoscale, and the color shifts to red.

…

There’s also an October 4, 2023 overview article by Tekla S. Perry and Margo Anderson for the IEEE Spectrum about the magazine’s almost twenty-five years of reporting on quantum dots

Image credit: Brandon Palacio/IEEE Spectrum

Your Guide to the Newest Nobel Prize: Quantum Dots

What you need to know—and what we’ve reported—about this year’s Chemistry award

…

It’s not a long article and it has a heavy focus on the IEEEE’s (Institute of Electrical and Electtronics Engineers) the road quantum dots have taken to become applications and being commercialized.

Congratulations to Moungi Bawendi, Louis Brus, and Alexei Ekimov!