The nanoparticles in question are lipid nanoparticles designed for delivery to the lungs and they are somewhat similar to the ones in some of the COVID-19 vaccines (mRNA vaccines). From a March 30, 2023 news item on Nanowerk,

Engineers at MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology] and the University of Massachusetts Medical School have designed a new type of nanoparticle that can be administered to the lungs, where it can deliver messenger RNA encoding useful proteins.

With further development, these particles could offer an inhalable treatment for cystic fibrosis and other diseases of the lung, the researchers say.

“This is the first demonstration of highly efficient delivery of RNA to the lungs in mice. We are hopeful that it can be used to treat or repair a range of genetic diseases, including cystic fibrosis,” says Daniel Anderson, a professor in MIT’s Department of Chemical Engineering and a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and Institute for Medical Engineering and Science (IMES).

In a study of mice, Anderson and his colleagues used the particles to deliver mRNA encoding the machinery needed for CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. That could open the door to designing therapeutic nanoparticles that can snip out and replace disease-causing genes.

A March 30, 2023 MIT news release, also on EurekAlert, which originated the news item, describes the research in more detail,

…

Targeting the lungs

Messenger RNA holds great potential as a therapeutic for treating a variety of diseases caused by faulty genes. One obstacle to its deployment thus far has been difficulty in delivering it to the right part of the body, without off-target effects. Injected nanoparticles often accumulate in the liver, so several clinical trials evaluating potential mRNA treatments for diseases of the liver are now underway. RNA-based Covid-19 vaccines, which are injected directly into muscle tissue, have also proven effective. In many of those cases, mRNA is encapsulated in a lipid nanoparticle — a fatty sphere that protects mRNA from being broken down prematurely and helps it enter target cells.

Several years ago, Anderson’s lab set out to design particles that would be better able to transfect the epithelial cells that make up most of the lining of the lungs. In 2019, his lab created nanoparticles that could deliver mRNA encoding a bioluminescent protein to lung cells. Those particles were made from polymers instead of lipids, which made them easier to aerosolize for inhalation into the lungs. However, more work is needed on those particles to increase their potency and maximize their usefulness.

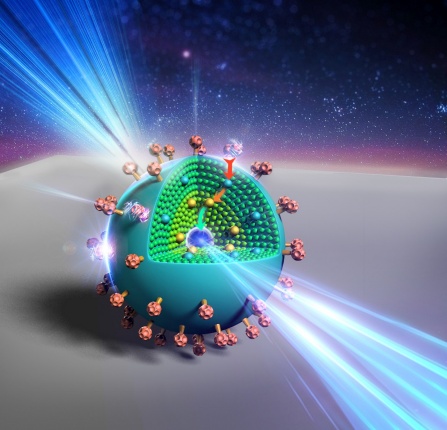

In their new study, the researchers set out to develop lipid nanoparticles that could target the lungs. The particles are made up of molecules that contain two parts: a positively charged headgroup and a long lipid tail. The positive charge of the headgroup helps the particles to interact with negatively charged mRNA, and it also help mRNA to escape from the cellular structures that engulf the particles once they enter cells.

The lipid tail structure, meanwhile, helps the particles to pass through the cell membrane. The researchers came up with 10 different chemical structures for the lipid tails, along with 72 different headgroups. By screening different combinations of these structures in mice, the researchers were able to identify those that were most likely to reach the lungs.

Efficient delivery

In further tests in mice, the researchers showed that they could use the particles to deliver mRNA encoding CRISPR/Cas9 components designed to cut out a stop signal that was genetically encoded into the animals’ lung cells. When that stop signal is removed, a gene for a fluorescent protein turns on. Measuring this fluorescent signal allows the researchers to determine what percentage of the cells successfully expressed the mRNA.

After one dose of mRNA, about 40 percent of lung epithelial cells were transfected, the researchers found. Two doses brought the level to more than 50 percent, and three doses up to 60 percent. The most important targets for treating lung disease are two types of epithelial cells called club cells and ciliated cells, and each of these was transfected at about 15 percent.

“This means that the cells we were able to edit are really the cells of interest for lung disease,” Li says. “This lipid can enable us to deliver mRNA to the lung much more efficiently than any other delivery system that has been reported so far.”

The new particles also break down quickly, allowing them to be cleared from the lung within a few days and reducing the risk of inflammation. The particles could also be delivered multiple times to the same patient if repeat doses are needed. This gives them an advantage over another approach to delivering mRNA, which uses a modified version of harmless adenoviruses. Those viruses are very effective at delivering RNA but can’t be given repeatedly because they induce an immune response in the host.

To deliver the particles in this study, the researchers used a method called intratracheal instillation, which is often used as a way to model delivery of medication to the lungs. They are now working on making their nanoparticles more stable, so they could be aerosolized and inhaled using a nebulizer.

The researchers also plan to test the particles to deliver mRNA that could correct the genetic mutation found in the gene that causes cystic fibrosis, in a mouse model of the disease. They also hope to develop treatments for other lung diseases, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, as well as mRNA vaccines that could be delivered directly to the lungs.

Here’s a link to and a citation from the paper,

Combinatorial design of nanoparticles for pulmonary mRNA delivery and genome editing by Bowen Li, Rajith Singh Manan, Shun-Qing Liang, Akiva Gordon, Allen Jiang, Andrew Varley, Guangping Gao, Robert Langer, Wen Xue & Daniel Anderson. Nature Biotechnology (2023) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-023-01679-x Published 30 March 2023

This paper is behind a paywall.