A May 29, 2013 news item on Azonano features a new study for the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on nanoscale technology and lithium-ion (li-ion) batteries for electric vehicles,

Lithium (Li-ion) batteries used to power plug-in hybrid and electric vehicles show overall promise to “fuel” these vehicles and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but there are areas for improvement to reduce possible environmental and public health impacts, according to a “cradle to grave” study of advanced Li-ion batteries recently completed by Abt Associates for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

“While Li-ion batteries for electric vehicles are definitely a step in the right direction from traditional gasoline-fueled vehicles and nickel metal-hydride automotive batteries, some of the materials and methods used to manufacture them could be improved,” said Jay Smith, an Abt senior analyst and co-lead of the life-cycle assessment.

Smith said, for example, the study showed that the batteries that use cathodes with nickel and cobalt, as well as solvent-based electrode processing, show the highest potential for certain environmental and human health impacts. The environmental impacts, Smith explained, include resource depletion, global warming, and ecological toxicity—primarily resulting from the production, processing and use of cobalt and nickel metal compounds, which can cause adverse respiratory, pulmonary and neurological effects in those exposed.

There are viable ways to reduce these impacts, he said, including cathode material substitution, solvent-less electrode processing and recycling of metals from the batteries.

The May 28, 2013 Abt Associates news release, which originated the news item, describes some of the findings,

Among other findings, Shanika Amarakoon, an Abt associate who co-led the life-cycle assessment with Smith, said global warming and other environmental and health impacts were shown to be influenced by the electricity grids used to charge the batteries when driving the vehicles.

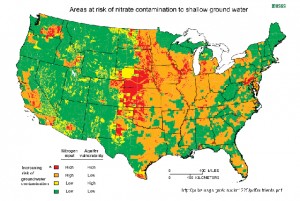

“These impacts are sensitive to local and regional grid mixes,” Amarakoon said. “If the batteries in use are drawing power from the grids in the Midwest or South, much of the electricity will be coming from coal-fired plants. If it’s in New England or California, the grids rely more on renewables and natural gas, which emit less greenhouse gases and other toxic pollutants.” However,” she added, “impacts from the processing and manufacture of these batteries should not be overlooked.”

In terms of battery performance, Smith said that “the nanotechnology applications that Abt assessed were single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs), which are currently being researched for use as anodes as they show promise for improving the energy density and ultimate performance of the Li-ion batteries in vehicles. What we found, however, is that the energy needed to produce the SWCNT anodes in these early stages of development is prohibitive. Over time, if researchers focus on reducing the energy intensity of the manufacturing process before commercialization, the environmental profile of the technology has the potential to improve dramatically.”

Abt’s Application of Life-Cycle Assessment to Nanoscale Technology: Lithium-ion Batteries for Electric Vehicles can be found here, all 126 pp.

This assessment was performed under the auspices of an interesting assortment of agencies (from the news release),

The research for the life-cycle assessment was undertaken through the Lithium-ion Batteries and Nanotechnology for Electric Vehicles Partnership, which was led by EPA’s Design for the Environment Program in the Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention and Toxics, and EPA’s National Risk Management Research Laboratory in the Office of Research and Development. [emphasis mine] The Partnership also included industry partners (i.e., battery manufacturers, recyclers, and suppliers, and other industry groups), the Department of Energy’s Argonne National Lab, Arizona State University, and the Rochester Institute of Technology

I highlighted the National Risk Management Research Laboratory as it reminded me of the lithium-ion battery fires in airplanes reported in January 2013. I realize that cars and planes are not the same thing but lithium-ion batteries have some well defined problems especially since the summer of 2006 when there was a series of li-ion battery laptop fires. From Tracy V. Wilson’s What causes laptop batteries to overheat? article for How stuff works.com (Note: A link has been removed),

In conjunction with the United States Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), Dell and Apple Computer announced large recalls of laptop batteries in the summer of 2006, followed by Toshiba and Lenovo. Sony manufactured all of the recalled batteries, and in October 2006, the company announced its own large-scale recall. Under the right circumstances, these batteries could overheat, potentially causing burns, an explosion or a fire.

Larry Greenemeier in a Jan. 17, 2013 article for Scientific American offers some details about the lithium-ion battery fires in airplanes and elsewhere,

Boeing’s Dreamliner has likely become a nightmare for the company, its airline customers and regulators worldwide. An inflight lithium-ion battery fire broke out Wednesday [Jan. 16, 2013] on an All Nippon Airways 787 over Japan, forcing an emergency landing. And another battery fire occurred last week aboard a Japan Airlines 787 at Boston’s Logan International Airport. Both battery failures resulted in release of flammable electrolytes, heat damage and smoke on the aircraft, according to the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

…

Lithium-ion batteries—used to power mobile phones, laptops and electric vehicles—have summoned plenty of controversy during their relatively brief existence. Introduced commercially in 1991, by the mid 2000s they had become infamous for causing fires in laptop computers.

More recently, the plug-in hybrid electric Chevy Volt’s lithium-ion battery packs burst into flames following several National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) tests to measure the vehicle’s ability to protect occupants from injury in a side collision. The NHTSA investigated and concluded in January 2012 that Chevy Volts and other electric vehicles do not pose a greater risk of fire than gasoline-powered vehicles.

Philip E. Ross in his Jan. 18, 2013 article about the airplane fires for IEEE’s (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) Spectrum provides some insight into the fires,

It seems that the batteries heated up in a self-accelerating pattern called thermal runaway. Heat from the production of electricity speeds up the production of electricity, and… you’re off. This sort of things happens in a variety of reactions, not just in batteries, let alone the Li-ion kind. But thermal runaway is particularly grave in Li-ion batteries because they pack a lot more power than the tried-and-true metal-hydride ones, not to speak of Ye Olde lead-acid.

It’s because of this very quality that Li-ion batteries found their first application in small mobile devices, where power is critical and fires won’t cost anyone his life. It’s also why it took so long for the new tech to find its way into electric and hybrid-electric cars.

…

Perhaps it would have been wiser of Boeing to go for the safest possible Li-ion design, even if it didn’t have quite as much oomph as possible. That’s what today’s main-line electric-drive cars do, as our colleague, John Voelcker, points out.

“The cells in the 787 [Dreamliner], from Japanese company GS Yuasa, use a cobalt oxide (CoO2) chemistry, just as mobile-phone and laptop batteries do,” he writes in greencarreports.com. “That chemistry has the highest energy content, but it is also the most susceptible to overheating that can produce “thermal events” (which is to say, fires). Only one electric car has been built in volume using CoO2 cells, and that’s the Tesla Roadster. Only 2,500 of those cars will ever exist.” Most of today’s electric cars, Voelcker adds, use chemistries that trade some energy density for safety.

The Dreamliner (Boeing 787) is designed to be the lightest of airplanes and using a more energy dense but safer lithium-ion battery seems not to have been an acceptable trade-off. Interestingly, Boeing according to Ross still had a backlog of orders after the fires.

I find that some of the discussion about risk and nanotechnology-enabled products oddly disconnected. There are the concerns about what happens at the nanoscale (environmental implications, etc.) but that discussion is divorced from some macroscale issues such as battery fires. Taken to absurd lengths, technology at the nanoscale could be considered safe while macroscale issues are completely ignored. It’s as if our institutions are not yet capable of managing multiple scales at once.

For more about an emphasis on scale and other minutiae (pun intended), there’s my May 28, 2013 posting about Steffen Foss Hansen’s plea to revise current European Union legislation to create more categories for nanotechnology regulation, amongst other things.

For more about airplanes and their efforts to get more energy efficient, there’s my May 27, 2013 posting about a biofuel study in Australia.