In fact, I have two items about fungi and I’m starting with the essay first.

Giving thanks for fungi

Antonis Rokas, professor at Venderbilt University (Nashville, Tennessee, US), has written a November 25, 2019 essay for The Conversation (h/t phys.org Nov.26.19) featuring fungi and food, Note: Links have been removed),

…

I am an evolutionary biologist studying fungi, a group of microbes whose domestication has given us many tasty products. I’ve long been fascinated by two questions: What are the genetic changes that led to their domestication? And how on Earth did our ancestors figure out how to domesticate them?

…

The hybrids in your lager

As far as domestication is concerned, it is hard to top the honing of brewer’s yeast. The cornerstone of the baking, brewing and wine-making industries, brewer’s yeast has the remarkable ability to turn the sugars of plant fruits and grains into alcohol. How did brewer’s yeast evolve this flexibility?

By discovering new yeast species and sequencing their genomes, scientists know that some yeasts used in brewing are hybrids; that is, they’re descendants of ancient mating unions of individuals from two different yeast species. Hybrids tend to resemble both parental species – think of wholpins (whale-dolphin) or ligers (lion-tiger).

… What is still unknown is whether hybridization is the norm or the exception in the yeasts that humans have used for making fermented beverages for millennia.

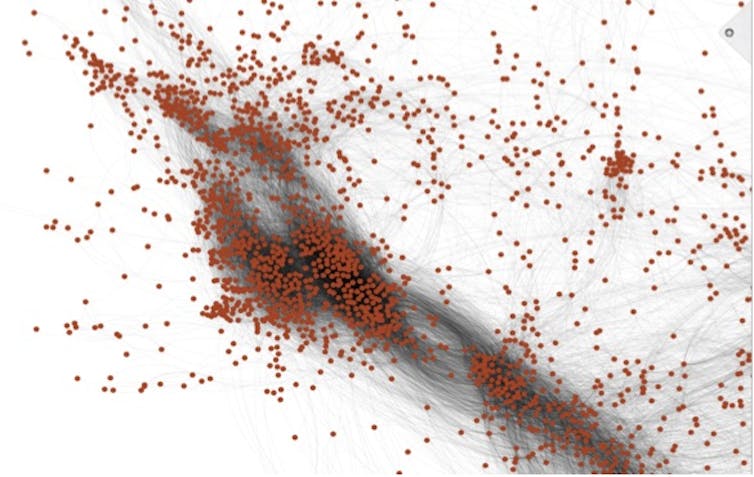

To address this question, a team led by graduate student Quinn Langdon at the University of Wisconsin and another team led by postdoctoral fellow Brigida Gallone at the Universities of Ghent and Leuven in Belgium examined the genomes of hundreds of yeasts involved in brewing and wine making. Their bottom line? Hybrids rule.

For example, a quarter of yeasts collected from industrial environments, including beer and wine manufacturers, are hybrids.

…

The mutants in your cheese

Comparing the genomes of domesticated fungi to their wild relatives helps scientists understand the genetic changes that gave rise to some favorite foods and drinks. But how did our ancestors actually domesticate these wild fungi? None of us was there to witness how it all started. To solve this mystery, scientists are experimenting with wild fungi to see if they can evolve into organisms resembling those that we use to make our food today.

Benjamin Wolfe, a microbiologist at Tufts University, and his team addressed this question by taking wild Penicillium mold and growing the samples for one month in his lab on a substance that included cheese. That may sound like a short period for people, but it is one that spans many generations for fungi.

The wild fungi are very closely related to fungal strains used by the cheese industry in the making of Camembert cheese, but look very different from them. For example, wild strains are green and smell, well, moldy compared to the white and odorless industrial strains.

For Wolfe, the big question was whether he could experimentally recreate, and to what degree, the process of domestication. What did the wild strains look and smell like after a month of growth on cheese? Remarkably, what he and his team found was that, at the end of the experiment, the wild strains looked much more similar to known industrial strains than to their wild ancestor. For example, they were white in color and smelled much less moldy.

…

… how did the wild strain turn into a domesticated version? Did it mutate? By sequencing the genomes of both the wild ancestors and the domesticated descendants, and measuring the activity of the genes while growing on cheese, Wolfe’s team figured out that these changes did not happen through mutations in the organisms’ genomes. Rather, they most likely occurred through chemical alterations that modify the activity of specific genes but don’t actually change the genetic code. Such so-called epigenetic modifications can occur much faster than mutations.

…

Fantastic Fungi Futures (FFF) Nov. 29, Dec. 1, and Dec. 4, 2019 events in Toronto, Canada

The ArtSci Salon emailed me a November 23, 2019 announcement about a special series being presented in partnership with the Mycological Society of Toronto (MST) on the topic of fungi,

Fantastic Fungi Futures a discussion, a mini exhibition, a special screening, and a workshop revolving around Fungi and their versatile nature.

NOV 29 [2019], 6:00-8:00 PM Fantastic Fungi Futures (FFF): a roundtable discussion and popup exhibition.

Join us for a roundtable discussion. what are the potentials of fungi? Our guests will share their research, as well as professional and artistic practice dealing with the taxonomy and the toxicology, the health benefits and the potentials for sustainability, as well as the artistic and architectural virtues of fungi and mushrooms. The Exhibition will feature photos and objects created by local and Canadian artists who have been working with mushrooms and fungi.

This discussion is in anticipation of the special screening of Fantastic Fungi at the HotDocs Cinema on Dec 1 [2019] our guests:James Scott,Occupational & Environmental Health, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, UofT; Marshall Tyler, Director of Research, Field Trip, Toronto; Rotem Petranker, PhD student, Social Psychology, York University; Nourin Aman, PhD student, fungal biology and Systematics lab, Punjab University; Sydney Gram, PhD student, Ecology & Evolutionary Biology student researcher (UofT/ROM); [and] Tosca Teran, Interdisciplinary artist.

DEC. 1 [2019], 6:15 pm join us to the screening of Fantastic Fungi, at the HotDocs Cinemaget your tickets herehttps://boxoffice.hotdocs.ca/websales/pages/info.aspx?evtinfo=104145~fff311b7-cdad-4e14-9ae4-a9905e1b9cb0 afterward, some of us will be heading to the Pauper’s Pub, just across from the HotDocs Cinema

DEC. 4 [2019], 7:00-10:00PM Multi-species entanglements:Sculpting with Mycelium, @InterAccess, 950 Dupont St., Unit 1

This workshop is a continuation of ArtSci Salon’s Fantastic Fungi Futures event and the HotDocs screening of Fantastic Fungi.this workshop is open to public to attend, however, pre-registration is required. $5.00 to form a mycelium bowl to take home.

During this workshop Tosca Teran introduces the amazing potential of Mycelium for collaboration at the intersection of art and science. Participants learn how to transform their kitchens and closets in to safe, mini-Mycelium biolabs and have the option to leave the workshop with a live Mycelium planter/bowl form, as well as a wide array of possibilities of how they might work with this sustainable bio-material.

Bios

Nourin Aman is a PhD student at fungal biology and Systematics lab at Punjab University, Lahore, Pakistan. She is currently a visiting PhD student at the Mycology lab, Royal Ontario Museum. Her research revolves around comparison between macrofungal biodiversity of some reserve forests of Punjab, Pakistan.Her interest is basically to enlist all possible macrofungi of reserve forests under study and describe new species as well from area as our part of world still has many species to be discovered and named. She will be discussing factors which are affecting the fungal biodiversity in these reserve forests.

Sydney Gram is an Ecology & Evolutionary Biology student researcher (UofT/ROM)

Rotem Petranker- Bsc in psychology from the University of Toronto and a MA in social psychology from York University. Rotem is currently a PhD student in York’s clinical psychology program. His main research interest is affect regulation, and the way it interacts with sustained attention, mind wandering, and creativity. Rotem is a founding member oft the Psychedelic Studies Research Program at the University of Toronto, has published work on microdosing, and presented original research findings on psychedelic research in several conferences. He feels strongly that the principles of Open Science are necessary in order to do good research, and is currently in the process of starting the first lab study of microdosing in Canada.

James Scott– PhD, is a ARMCCM Professor and Head Division of Occupational & Environmental Health, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of TorontoUAMH Fungal Biobank: http://www.uamh.caUniversity Profile: http://www.dlsph.utoronto.ca/faculty-profile/scott-james-a/Research Laboratory: http://individual.utoronto.ca/jscottCommercial Laboratory: http://www.sporometrics.com

Marshall Tyler– Director of Research, Field Trip. Marshall is a scientist with a deep interest in psychoactive molecules. His passion lies in guiding research to arrive at a deeper understanding of consciousness with the ultimate goal of enhancing wellbeing. At Field Trip, he is helping to develop a lab in Jamaica to explore the chemical and biological complexities of psychoactive fungi.

Tosca Teran, aka Nanotopia, is an Multi-disciplinary artist. Her work has been featured at SOFA New York, Culture Canada, and The Toronto Design Exchange. Tosca has been awarded artist residencies with The Ayatana Research Program in Ottawa and The Icelandic Visual Artists Association through Sím, Reykjavik Iceland and Nes artist residency in Skagaströnd, Iceland. In 2019 she was one of the first Bio-Artists in residence at the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto in partnership with the Ontario Science Centre as part of the Alien Agencies Collective. A recipient of the 2019 BigCi Environmental Award at Wollemi National Park within the UNESCO World Heritage site in the Greater Blue Mountains. Tosca started collaborating artistically with Algae, Physarum polycephalum, and Mycelium in 2016, translating biodata from non-human organisms into music.@MothAntler @nanopodstudio www.toscateran.com www.nanotopia.net8

A trailer has been provided for the movie mentioned in the announcement (from the Fantastic Fungi screening webpage on the Mycological Society of Toronto website),

You can find the ArtSci Salon here and the Mycological Society of Toronto (MST) here.