It’s been a while since I’ve had a story from one of Germany’s Franhaufer Institutes. Their stories are usually focused on research that’s about to commercialized but that’s not the case this time according to an April 28, 2016 news item on Nanowerk,

It is still unclear what the impact is on humans, animals and plants of synthetic nanomaterials released into the environment or used in products. It’s very difficult to detect these nanomaterials in the environment since the concentrations are so low and the particles so small. Now the partners in the NanoUmwelt project have developed a method that is capable of identifying even minute amounts of nanomaterials in environmental samples.

An April 28, 2016 Fraunhofer Institute press release, which originated the news item, provides more detail about the technology and about the NanoUmwelt project along with a touch of whimsy,

Tiny dwarves keep our mattresses clean, repair damage to our teeth, stop eggs sticking to our pans, and extend the shelf life of our food. We are talking about nanomaterials – “nano” comes from the Greek word for “dwarf”. These particles are just a few billionths of a meter small, and they are used in a wide range of consumer products. However, up to now the impact of these materials on the environment has been largely unknown, and information is lacking on the concentrations and forms in which they are present there. “It’s true that many laboratory studies have examined the effect of nanomaterials on human and animal cells. To date, though, it hasn’t been possible to detect very small amounts in environmental samples,” says Dr. Yvonne Kohl from the Fraunhofer Institute for Biomedical Engineering IBMT in Sulzbach.

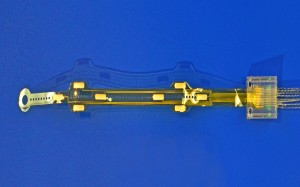

A millionth of a milligram per literThat is precisely the objective of the NanoUmwelt project. The interdisciplinary project team is made up of eco- and human toxicologists, physicists, chemists and biologists, and they have just managed to take their first major step forward in achieving their goal: they have developed a method for testing a variety of environmental samples such as river water, animal tissue, or human urine and blood that can detect nanomaterials at a concentration level of nanogram per liter (ppb – parts per billion). That is equivalent to half a sugar cube in the volume of water contained in 1,000 competition swimming pools. Using the new method, it is now possible to detect not just large amounts of nanomaterials in clear fluids, as was previously the case, but also very few particles in complex substance mixtures such as human blood or soil samples. The approach is based on field-flow fractionation (FFF), which can be used to separate complex heterogeneous mixtures of fluids and particles into their component parts – while simultaneously sorting the key components by size. This is achieved by the combination of a controlled flow of fluid and a physical separation field, which acts perpendicularly on the flowing suspension.

For the detection process to work, environmental samples have to be appropriately processed. The team from Fraunhofer IBMT’s Bioprocessing & Bioanalytics Department prepared river water, human urine, and fish tissue to be fit for the FFF device. “We prepare the samples with special enzymes. In this process, we have to make sure that the nanomaterials are not destroyed or changed. This allows us to detect the real amounts and forms of the nanomaterials in the environment,” explains Kohl. The scientists have special expertise when it comes to providing, processing and storing human tissue samples. Fraunhofer IBMT has been running the “German Environmental Specimen Bank (ESB) – Human Samples”since January 2012 on behalf of Germany’s Environment Agency (UBA). Each year the research institute collects blood and urine samples from 120 volunteers in four cities in Germany. Individual samples are a valuable tool for mapping the trends over time of human exposure to pollutants. ”In addition, blood and urine samples have been donated for the NanoUmwelt project and put into cryostorage at Fraunhofer IBMT. We used these samples to develop our new detection method,” says Dr. Dominik Lermen, manager of the working group on Biomonitoring & Cryobanks at Fraunhofer IBMT. After approval by the UBA, some of the human samples in the ESB archive may also be examined using the new method.

Developing new cell culture modelsNanomaterials end up in the environment via different pathways, inter alia the sewage system. Human beings and animals presumably absorb them through biological barriers such as the lung or intestine. The project team is simulating these processes in petri dishes in order to understand how nanomaterials are transported across these barriers. “It’s a very complex process involving an extremely wide range of cells and layers of tissue,” explains Kohl. The researchers replicate the processes in a way as realistic as possible. They do this by, for instance, measuring the electrical flows within the barriers to determine the functionality of these barriers – or by simulating lung-air interaction using clouds of artificial fog. In the first phase of the NanoUmwelt project, the IBMT team succeeded in developing several cell culture models for the transport of nanomaterials across biological barriers. IBMT worked together with the Fraunhofer Institute for Molecular Biology and Applied Ecology IME, which used pluripotent stem cells to develop a model for investigating cardiotoxicity. Empa, the Swiss partner in the project, delivered a placental barrier model for studying the transport of nanomaterials between mother and child.

Next, the partners want to use their method to measure the concentrations of nanoparticles in a wide variety of environmental samples. They will then analyze the results obtained so as to be in a better position to assess the behavior of nanomaterials in the environment and their potential danger for humans, animals, and the environment. “Our next goal is to detect particles in even smaller quantities,” says Kohl. To achieve this, the scientists are planning to use special filters to remove distracting elements from the environmental samples, and they are looking forward to develop new processing techniques.

NanoUmwelt – the objectiveThe NanoUmwelt research project was launched in October 2014 and will last for 36 months. Its objective is to develop methods for detecting minute amounts of nanomaterials in environmental samples. Using this information, the project partners will assess the effect of nanomaterials on humans, animals, and the environment. They are focusing on commercially significant, slowly degradable, metallic (silver, titanium dioxide), carbonic (carbon nanotubes) and polymer-based (polystyrene) nanomaterials.

http://www.nanopartikel.info/projekte/laufende-projekte/nanoumwelt

NanoUmwelt – the partners

The German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) is providing the NanoUmwelt project with 1.8 million euros of funding as part of its NanoCare program. Led by Postnova Analytics GmbH, ten further partners are collaborating together on the project. Besides the Fraunhofer Institutes for Biomedical Engineering IBMT and for Molecular Biology and Applied Ecology IME, these partners include Germany’s Environment Agency, Empa (the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology), PlasmaChem GmbH, Senova GmbH (biological sciences and engineering), fzmb GmbH (Research Centre of Medical Technology and Biotechnology), the universities of Trier and Frankfurt, and the Rhine Water Control Station in Worms.

http://www.nanopartikel.info/projekte/laufende-projekte/nanoumwelt

How small is nano?A nanometer (nm) is a billionth of a meter. To put this into context: the size of a single nanoparticle relative to a football is the same as that of a football relative to the earth. In the main, nanoscopic particles are not new materials. It’s simply that the increased overall surface area of these tiny particles gives them new functionalities as against larger particles of the same material.

The German Environmental Specimen BankThe German Environmental Specimen Bank (ESB) provides the country’s Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB) with a scientific basis both for adopting appropriate measures concerning environment and nature conservation and for monitoring the success of those measures. The human samples collected by the Fraunhofer Institute for Biomedical Engineering IBMT on behalf of Germany’s Environment Agency (UBA) give an overview of human exposure to environmental pollutants.

Assuming I’ve understood this correctly, the NanoUmwelt project will be ending in 2017 (36 months in total) and the researchers have expended 1/2 of the time (18 months) allotted to developing a technique for measuring nanomaterials of heretofore unheard of quantities in environmental samples. With that done, researchers are now going to use the technique with human samples over the next 18 months.

![Polymer Opals Credit: Nick Saffel [downloaded from http://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/flexible-opals]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/FlexibleOpal-300x146.jpg)