Back in the fall of 2018 I came across one of those overexcited pieces about personalized medicine and gene editing tha are out there. This one came from an unexpected source, an author who is a “PhD Scientist in Medical Science (Blood and Vasculature” (from Rick Gierczak’s LinkedIn profile).

It starts our promisingly enough although I’m beginning to dread the use of the word ‘precise’ where medicine is concerned, (from a September 17, 2018 posting on the Science Borealis blog by Rick Gierczak (Note: Links have been removed),

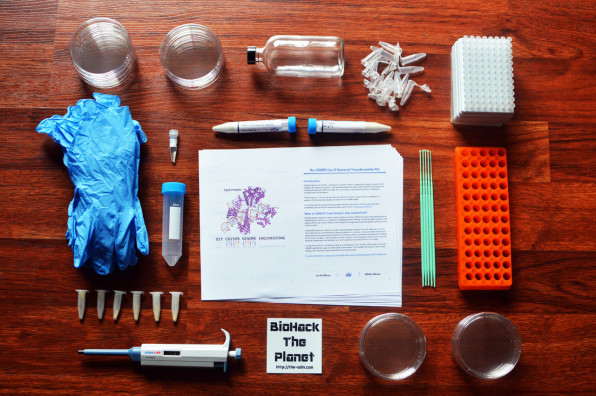

CRISPR-Cas9 technology was accidentally discovered in the 1980s when scientists were researching how bacteria defend themselves against viral infection. While studying bacterial DNA called clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR), they identified additional CRISPR-associated (Cas) protein molecules. Together, CRISPR and one of those protein molecules, termed Cas9, can locate and cut precise regions of bacterial DNA. By 2012, researchers understood that the technology could be modified and used more generally to edit the DNA of any plant or animal. In 2015, the American Association for the Advancement of Science chose CRISPR-Cas9 as science’s “Breakthrough of the Year”.

Today, CRISPR-Cas9 is a powerful and precise gene-editing tool [emphasis mine] made of two molecules: a protein that cuts DNA (Cas9) and a custom-made length of RNA that works like a GPS for locating the exact spot that needs to be edited (CRISPR). Once inside the target cell nucleus, these two molecules begin editing the DNA. After the desired changes are made, they use a repair mechanism to stitch the new DNA into place. Cas9 never changes, but the CRISPR molecule must be tailored for each new target — a relatively easy process in the lab. However, it’s not perfect, and occasionally the wrong DNA is altered [emphasis mine].

Note that Gierczak makes a point of mentioning that CRISPR/Cas9 is “not perfect.” And then, he gets excited (Note: Links have been removed),

CRISPR-Cas9 has the potential to treat serious human diseases, many of which are caused by a single “letter” mutation in the genetic code (A, C, T, or G) that could be corrected by precise editing. [emphasis mine] Some companies are taking notice of the technology. A case in point is CRISPR Therapeutics, which recently developed a treatment for sickle cell disease, a blood disorder that causes a decrease in oxygen transport in the body. The therapy targets a special gene called fetal hemoglobin that’s switched off a few months after birth. Treatment involves removing stem cells from the patient’s bone marrow and editing the gene to turn it back on using CRISPR-Cas9. These new stem cells are returned to the patient ready to produce normal red blood cells. In this case, the risk of error is eliminated because the new cells are screened for the correct edit before use.

The breakthroughs shown by companies like CRISPR Therapeutics are evidence that personalized medicine has arrived. [emphasis mine] However, these discoveries will require government regulatory approval from the countries where the treatment is going to be used. In the US, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has developed new regulations allowing somatic (i.e., non-germ) cell editing and clinical trials to proceed. [emphasis mine]

The potential treatment for sickle cell disease is exciting but Gierczak offers no evidence that this treatment or any unnamed others constitute proof that “personalized medicine has arrived.” In fact, Goldman Sachs, a US-based investment bank, makes the case that it never will .

Cost/benefit analysis

Edward Abrahams, president of the Personalized Medicine Coalition (US-based), advocates for personalized medicine while noting in passing, market forces as represented by Goldman Sachs in his May 23, 2018 piece for statnews.com (Note: A link has been removed),

…

One of every four new drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration over the last four years was designed to become a personalized (or “targeted”) therapy that zeros in on the subset of patients likely to respond positively to it. That’s a sea change from the way drugs were developed and marketed 10 years ago.

Some of these new treatments have extraordinarily high list prices. But focusing solely on the cost of these therapies rather than on the value they provide threatens the future of personalized medicine.

…

… most policymakers are not asking the right questions about the benefits of these treatments for patients and society. Influenced by cost concerns, they assume that prices for personalized tests and treatments cannot be justified even if they make the health system more efficient and effective by delivering superior, longer-lasting clinical outcomes and increasing the percentage of patients who benefit from prescribed treatments.

Goldman Sachs, for example, issued a report titled “The Genome Revolution.” It argues that while “genome medicine” offers “tremendous value for patients and society,” curing patients may not be “a sustainable business model.” [emphasis mine] The analysis underlines that the health system is not set up to reap the benefits of new scientific discoveries and technologies. Just as we are on the precipice of an era in which gene therapies, gene-editing, and immunotherapies promise to address the root causes of disease, Goldman Sachs says that these therapies have a “very different outlook with regard to recurring revenue versus chronic therapies.”

…

Let’s just chew on this one (contemplate) for a minute”curing patients may not be ‘sustainable business model’!”

Coming down to earth: policy

While I find Gierczak to be over-enthused, he, like Abrahams, emphasizes the importance of new policy, in his case, the focus is Canadian policy. From Gierczak’s September 17, 2018 posting (Note: Links have been removed),

In Canada, companies need approval from Health Canada. But a 2004 law called the Assisted Human Reproduction Act (AHR Act) states that it’s a criminal offence “to alter the genome of a human cell, or in vitroembryo, that is capable of being transmitted to descendants”. The Actis so broadly written that Canadian scientists are prohibited from using the CRISPR-Cas9 technology on even somatic cells. Today, Canada is one of the few countries in the world where treating a disease with CRISPR-Cas9 is a crime.

On the other hand, some countries provide little regulatory oversight for editing either germ or somatic cells. In China, a company often only needs to satisfy the requirements of the local hospital where the treatment is being performed. And, if germ-cell editing goes wrong, there is little recourse for the future generations affected.

The AHR Act was introduced to regulate the use of reproductive technologies like in vitrofertilization and research related to cloning human embryos during the 1980s and 1990s. Today, we live in a time when medical science, and its role in Canadian society, is rapidly changing. CRISPR-Cas9 is a powerful tool, and there are aspects of the technology that aren’t well understood and could potentially put patients at risk if we move ahead too quickly. But the potential benefits are significant. Updated legislation that acknowledges both the risks and current realities of genomic engineering [emphasis mine] would relieve the current obstacles and support a path toward the introduction of safe new therapies.

…

Criminal ban on human gene-editing of inheritable cells (in Canada)

I had no idea there was a criminal ban on the practice until reading this January 2017 editorial by Bartha Maria Knoppers, Rosario Isasi, Timothy Caulfield, Erika Kleiderman, Patrick Bedford, Judy Illes, Ubaka Ogbogu, Vardit Ravitsky, & Michael Rudnicki for (Nature) npj Regenerative Medicine (Note: Links have been removed),

Driven by the rapid evolution of gene editing technologies, international policy is examining which regulatory models can address the ensuing scientific, socio-ethical and legal challenges for regenerative and personalised medicine.1 Emerging gene editing technologies, including the CRISPR/Cas9 2015 scientific breakthrough,2 are powerful, relatively inexpensive, accurate, and broadly accessible research tools.3 Moreover, they are being utilised throughout the world in a wide range of research initiatives with a clear eye on potential clinical applications. Considering the implications of human gene editing for selection, modification and enhancement, it is time to re-examine policy in Canada relevant to these important advances in the history of medicine and science, and the legislative and regulatory frameworks that govern them. Given the potential human reproductive applications of these technologies, careful consideration of these possibilities, as well as ethical and regulatory scrutiny must be a priority.4

With the advent of human embryonic stem cell research in 1978, the birth of Dolly (the cloned sheep) in 1996 and the Raelian cloning hoax in 2003, the environment surrounding the enactment of Canada’s 2004 Assisted Human Reproduction Act (AHRA) was the result of a decade of polarised debate,5 fuelled by dystopian and utopian visions for future applications. Rightly or not, this led to the AHRA prohibition on a wide range of activities, including the creation of embryos (s. 5(1)(b)) or chimeras (s. 5(1)(i)) for research and in vitro and in vivo germ line alterations (s. 5(1)(f)). Sanctions range from a fine (up to $500,000) to imprisonment (up to 10 years) (s. 60 AHRA).

In Canada, the criminal ban on gene editing appears clear, the Act states that “No person shall knowingly […] alter the genome of a cell of a human being or in vitro embryo such that the alteration is capable of being transmitted to descendants;” [emphases mine] (s. 5(1)(f) AHRA). This approach is not shared worldwide as other countries such as the United Kingdom, take a more regulatory approach to gene editing research.1 Indeed, as noted by the Law Reform Commission of Canada in 1982, criminal law should be ‘an instrument of last resort’ used solely for “conduct which is culpable, seriously harmful, and generally conceived of as deserving of punishment”.6 A criminal ban is a suboptimal policy tool for science as it is inflexible, stifles public debate, and hinders responsiveness to the evolving nature of science and societal attitudes.7 In contrast, a moratorium such as the self-imposed research moratorium on human germ line editing called for by scientists in December 20158 can at least allow for a time limited pause. But like bans, they may offer the illusion of finality and safety while halting research required to move forward and validate innovation.

On October 1st, 2016, Health Canada issued a Notice of Intent to develop regulations under the AHRA but this effort is limited to safety and payment issues (i.e. gamete donation). Today, there is a need for Canada to revisit the laws and policies that address the ethical, legal and social implications of human gene editing. The goal of such a critical move in Canada’s scientific and legal history would be a discussion of the right of Canadians to benefit from the advancement of science and its applications as promulgated in article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights9 and article 15(b) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights,10 which Canada has signed and ratified. Such an approach would further ensure the freedom of scientific endeavour both as a principle of a liberal democracy and as a social good, while allowing Canada to be engaged with the international scientific community.

…

Even though it’s a bit old, I still recommend reading the open access editorial in full, if you have the time.

One last thing abut the paper, the acknowledgements,

Sponsored by Canada’s Stem Cell Network, the Centre of Genomics and Policy of McGill University convened a ‘think tank’ on the future of human gene editing in Canada with legal and ethics experts as well as representatives and observers from government in Ottawa (August 31, 2016). The experts were Patrick Bedford, Janetta Bijl, Timothy Caulfield, Judy Illes, Rosario Isasi, Jonathan Kimmelman, Erika Kleiderman, Bartha Maria Knoppers, Eric Meslin, Cate Murray, Ubaka Ogbogu, Vardit Ravitsky, Michael Rudnicki, Stephen Strauss, Philip Welford, and Susan Zimmerman. The observers were Geneviève Dubois-Flynn, Danika Goosney, Peter Monette, Kyle Norrie, and Anthony Ridgway.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Both McGill and the Stem Cell Network pop up again. A November 8, 2017 article about the need for new Canadian gene-editing policies by Tom Blackwell for the National Post features some familiar names (Did someone have a budget for public relations and promotion?),

It’s one of the most exciting, and controversial, areas of health science today: new technology that can alter the genetic content of cells, potentially preventing inherited disease — or creating genetically enhanced humans.

But Canada is among the few countries in the world where working with the CRISPR gene-editing system on cells whose DNA can be passed down to future generations is a criminal offence, with penalties of up to 10 years in jail.

This week, one major science group announced it wants that changed, calling on the federal government to lift the prohibition and allow researchers to alter the genome of inheritable “germ” cells and embryos.

The potential of the technology is huge and the theoretical risks like eugenics or cloning are overplayed, argued a panel of the Stem Cell Network.

The step would be a “game-changer,” said Bartha Knoppers, a health-policy expert at McGill University, in a presentation to the annual Till & McCulloch Meetings of stem-cell and regenerative-medicine researchers [These meetings were originally known as the Stem Cell Network’s Annual General Meeting {AGM}]. [emphases mine]

…

“I’m completely against any modification of the human genome,” said the unidentified meeting attendee. “If you open this door, you won’t ever be able to close it again.”

If the ban is kept in place, however, Canadian scientists will fall further behind colleagues in other countries, say the experts behind the statement say; they argue possible abuses can be prevented with good ethical oversight.

“It’s a human-reproduction law, it was never meant to ban and slow down and restrict research,” said Vardit Ravitsky, a University of Montreal bioethicist who was part of the panel. “It’s a sort of historical accident … and now our hands are tied.”

…

There are fears, as well, that CRISPR could be used to create improved humans who are genetically programmed to have certain facial or other features, or that the editing could have harmful side effects. Regardless, none of it is happening in Canada, good or bad.

…

In fact, the Stem Cell Network panel is arguably skirting around the most contentious applications of the technology. It says it is asking the government merely to legalize research for its own sake on embryos and germ cells — those in eggs and sperm — not genetic editing of embryos used to actually get women pregnant.

The highlighted portions in the last two paragraphs of the excerpt were written one year prior to the claims by a Chinese scientist that he had run a clinical trial resulting in gene-edited twins, Lulu and Nana. (See my my November 28, 2018 posting for a comprehensive overview of the original furor). I have yet to publish a followup posting featuring the news that the CRISPR twins may have been ‘improved’ more extensively than originally realized. The initial reports about the twins focused on an illness-related reason (making them HIV ‘immune’) but made no mention of enhanced cognitive skills a side effect of eliminating the gene that would make them HIV ‘immune’. To date, the researcher has not made the bulk of his data available for an in-depth analysis to support his claim that he successfully gene-edited the twins. As well, there were apparently seven other pregnancies coming to term as part of the researcher’s clinical trial and there has been no news about those births.

Risk analysis innovation

Before moving onto the innovation of risk analysis, I want to focus a little more on at least one of the risks that gene-editing might present. Gierczak noted that CRISPR/Cas9 is “not perfect,” which acknowledges the truth but doesn’t convey all that much information.

While the terms ‘precision’ and ‘scissors’ are used frequently when describing the CRISPR technique, scientists actually mean that the technique is significantly ‘more precise’ than other techniques but they are not referencing an engineering level of precision. As for the ‘scissors’, it’s an analogy scientists like to use but in fact CRISPR is not as efficient and precise as a pair of scissors.

Michael Le Page in a July 16, 2018 article for New Scientist lays out some of the issues (Note: A link has been removed),

A study of CRIPSR suggests we shouldn’t rush into trying out CRISPR genome editing inside people’s bodies just yet. The technique can cause big deletions or rearrangements of DNA [emphasis mine], says Allan Bradley of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in the UK, meaning some therapies based on CRISPR may not be quite as safe as we thought.

The CRISPR genome editing technique is revolutionising biology, enabling us to create new varieties of plants and animals and develop treatments for a wide range of diseases.

The CRISPR Cas9 protein works by cutting the DNA of a cell in a specific place. When the cell repairs the damage, a few DNA letters get changed at this spot – an effect that can be exploited to disable genes.

At least, that’s how it is supposed to work. But in studies of mice and human cells, Bradley’s team has found that in around a fifth of cells, CRISPR causes deletions or rearrangements more than 100 DNA letters long. These surprising changes are sometimes thousands of letters long.

…

“I do believe the findings are robust,” says Gaetan Burgio of the Australian National University, an expert on CRISPR who has debunked previous studies questioning the method’s safety. “This is a well-performed study and fairly significant.”

…

I covered the Bradley paper and the concerns in a July 17, 2018 posting ‘The CRISPR ((clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)-CAS9 gene-editing technique may cause new genetic damage kerfuffle‘. (The ‘kerfufle’ was in reference to a report that the CRISPR market was affected by the publication of Bradley’s paper.)

Despite Health Canada not moving swiftly enough for some researchers, they have nonetheless managed to release an ‘outcome’ report about a consultation/analysis started in October 2016. Before getting to the consultation’s outcome, it’s interesting to look at how the consultation’s call for response was described (from Health Canada’s Toward a strengthened Assisted Human Reproduction Act ; A Consultation with Canadians on Key Policy Proposals webpage),

In October 2016, recognizing the need to strengthen the regulatory framework governing assisted human reproduction in Canada, Health Canada announced its intention to bring into force the dormant sections of the Assisted Human Reproduction Act and to develop the necessary supporting regulations.

This consultation document provides an overview of the key policy proposals that will help inform the development of regulations to support bringing into force Section 10, Section 12 and Sections 45-58 of the Act. Specifically, the policy proposals describe the Department’s position on the following:

Section 10: Safety of Donor Sperm and Ova

- Scope and application

- Regulated parties and their regulatory obligations

- Processing requirements, including donor suitability assessment

- Record-keeping and traceability

Section 12: Reimbursement

- Expenditures that may be reimbursed

- Process for reimbursement

- Creation and maintenance of records

Sections 45-58: Administration and Enforcement

- Scope of the administration and enforcement framework

- Role of inspectors designated under the Act

The purpose of the document is to provide Canadians with an opportunity to review the policy proposals and to provide feedback [emphasis mine] prior to the Department finalizing policy decisions and developing the regulations. In addition to requesting stakeholders’ general feedback on the policy proposals, the Department is also seeking input on specific questions, which are included throughout the document.

It took me a while to find the relevant section (in particular, take note of ‘Federal Regulatory Oversight’),

3.2. AHR in Canada Today

Today, an increasing number of Canadians are turning to AHR technologies to grow or build their families. A 2012 Canadian studyFootnote 1 found that infertility is on the rise in Canada, with roughly 16% of heterosexual couples experiencing infertility. In addition to rising infertility, the trend of delaying marriage and parenthood, scientific advances in cryopreserving ova, and the increasing use of AHR by LGBTQ2 couples and single parents to build a family are all contributing to an increase in the use of AHR technologies.

The growing use of reproductive technologies by Canadians to help build their families underscores the need to strengthen the AHR Act. While the approach to regulating AHR varies from country to country, Health Canada has considered international best practices and the need for regulatory alignment when developing the proposed policies set out in this document. …

3.2.1 Federal Regulatory Oversight

Although the scope of the AHR Act was significantly reduced in 2012 and some of the remaining sections have not yet been brought into force, there are many important sections of the Act that are currently administered and enforced by Health Canada, as summarized generally below:

…

Section 5: Prohibited Scientific and Research Procedures

Section 5 prohibits certain types of scientific research and clinical procedures that are deemed unacceptable, including: human cloning, the creation of an embryo for non-reproductive purposes, maintaining an embryo outside the human body beyond the fourteenth day, sex selection for non-medical reasons, altering the genome in a way that could be transmitted to descendants, and creating a chimera or a hybrid. [emphasis mine]

….

It almost seems as if the they were hiding the section that broached the human gene-editing question. It doesn’t seem to have worked as it appears, there are some very motivated parties determined to reframe the discussion. Health Canada’s ‘outocme’ report, published March 2019, What we heard: A summary of scanning and consultations on what’s next for health product regulation reflects the success of those efforts,

1.0 Introduction and Context

Scientific and technological advances are accelerating the pace of innovation. These advances are increasingly leading to the development of health products that are better able to predict, define, treat, and even cure human diseases. Globally, many factors are driving regulators to think about how to enable health innovation. To this end, Health Canada has been expanding beyond existing partnerships and engaging both domestically and internationally. This expanding landscape of products and services comes with a range of new challenges and opportunities.

In keeping up to date with emerging technologies and working collaboratively through strategic partnerships, Health Canada seeks to position itself as a regulator at the forefront of health innovation. Following the targeted sectoral review of the Health and Biosciences Sector Regulatory Review consultation by the Treasury Board Secretariat, Health Canada held a number of targeted meetings with a broad range of stakeholders.

This report outlines the methodologies used to look ahead at the emerging health technology environment, [emphasis mine] the potential areas of focus that resulted, and the key findings from consultations.

…

… the Department identified the following key drivers that are expected to shape the future of health innovation:

- The use of “big data” to inform decision-making: Health systems are generating more data, and becoming reliant on this data. The increasing accuracy, types, and volume of data available in real time enable automation and machine learning that can forecast activity, behaviour, or trends to support decision-making.

- Greater demand for citizen agency: Canadians increasingly want and have access to more information, resources, options, and platforms to manage their own health (e.g., mobile apps, direct-to-consumer services, decentralization of care).

- Increased precision and personalization in health care delivery: Diagnostic tools and therapies are increasingly able to target individual patients with customized therapies (e.g., individual gene therapy).

- Increased product complexity: Increasingly complex products do not fit well within conventional product classifications and standards (e.g., 3D printing).

- Evolving methods for production and distribution: In some cases, manufacturers and supply chains are becoming more distributed, challenging the current framework governing production and distribution of health products.

- The ways in which evidence is collected and used are changing: The processes around new drug innovation, research and development, and designing clinical trials are evolving in ways that are more flexible and adaptive.

With these key drivers in mind, the Department selected the following six emerging technologies for further investigation to better understand how the health product space is evolving:

- Artificial intelligence, including activities such as machine learning, neural networks, natural language processing, and robotics.

- Advanced cell therapies, such as individualized cell therapies tailor-made to address specific patient needs.

- Big data, from sources such as sensors, genetic information, and social media that are increasingly used to inform patient and health care practitioner decisions.

- 3D printing of health products (e.g., implants, prosthetics, cells, tissues).

- New ways of delivering drugs that bring together different product lines and methods (e.g., nano-carriers, implantable devices).

- Gene editing, including individualized gene therapies that can assist in preventing and treating certain diseases.

Next, to test the drivers identified and further investigate emerging technologies, the Department consulted key organizations and thought leaders across the country with expertise in health innovation. To this end, Health Canada held seven workshops with over 140 representatives from industry associations, small-to-medium sized enterprises and start-ups, larger multinational companies, investors, researchers, and clinicians in Ottawa, Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver. [emphases mine]

…

The ‘outocme’ report, ‘What we heard …’, is well worth reading in its entirety; it’s about 9 pp.

I have one comment, ‘stakeholders’ don’t seem to include anyone who isn’t “from industry associations, small-to-medium sized enterprises and start-ups, larger multinational companies, investors, researchers, and clinician” or from “Ottawa, Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver.” Aren’t the rest of us stakeholders?

Innovating risk analysis

This line in the report caught my eye (from Health Canada’s Toward a strengthened Assisted Human Reproduction Act ; A Consultation with Canadians on Key Policy Proposals webpage),

There is increasing need to enable innovation in a flexible, risk-based way, with appropriate oversight to ensure safety, quality, and efficacy. [emphases mine]

It reminded me of the 2019 federal budget (from my March 22, 2019 posting). One comment before proceeding, regulation and risk are tightly linked and, so, by innovating regulation they are by exttension alos innovating risk analysis,

… Budget 2019 introduces the first three “Regulatory Roadmaps” to specifically address stakeholder issues and irritants in these sectors, informed by over 140 responses [emphasis mine] from businesses and Canadians across the country, as well as recommendations from the Economic Strategy Tables.

Introducing Regulatory Roadmaps

These Roadmaps lay out the Government’s plans to modernize regulatory frameworks, without compromising our strong health, safety, and environmental protections. They contain proposals for legislative and regulatory amendments as well as novel regulatory approaches to accommodate emerging technologies, including the use of regulatory sandboxes and pilot projects—better aligning our regulatory frameworks with industry realities.

Budget 2019 proposes the necessary funding and legislative revisions so that regulatory departments and agencies can move forward on the Roadmaps, including providing the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Health Canada and Transport Canada with up to $219.1 million over five years, starting in 2019–20, (with $0.5 million in remaining amortization), and $3.1 million per year on an ongoing basis.

In the coming weeks, the Government will be releasing the full Regulatory Roadmaps for each of the reviews, as well as timelines for enacting specific initiatives, which can be grouped in the following three main areas:

What Is a Regulatory Sandbox? Regulatory sandboxes are controlled “safe spaces” in which innovative products, services, business models and delivery mechanisms can be tested without immediately being subject to all of the regulatory requirements.

– European Banking Authority, 2017

…

Establishing a regulatory sandbox for new and innovative medical products

The regulatory approval system has not kept up with new medical technologies and processes. Health Canada proposes to modernize regulations to put in place a regulatory sandbox for new and innovative products, such as tissues developed through 3D printing, artificial intelligence, and gene therapies targeted to specific individuals. [emphasis mine]

Modernizing the regulation of clinical trials

Industry and academics have expressed concerns that regulations related to clinical trials are overly prescriptive and inconsistent. Health Canada proposes to implement a risk-based approach [emphasis mine] to clinical trials to reduce costs to industry and academics by removing unnecessary requirements for low-risk drugs and trials. The regulations will also provide the agri-food industry with the ability to carry out clinical trials within Canada on products such as food for special dietary use and novel foods.

Does the government always get 140 responses from a consultation process? Moving on, I agree with finding new approaches to regulatory processes and oversight and, by extension, new approaches to risk analysis.

Earlier in this post, I asked if someone had a budget for public relations/promotion. I wasn’t joking. My March 22, 2019 posting also included these line items in the proposed 2019 budget,

Budget 2019 proposes to make additional investments in support of the following organizations:

Stem Cell Network: Stem cell research—pioneered by two Canadians in the 1960s [James Till and Ernest McCulloch]—holds great promise for new therapies and medical treatments for respiratory and heart diseases, spinal cord injury, cancer, and many other diseases and disorders. The Stem Cell Network is a national not-for-profit organization that helps translate stem cell research into clinical applications and commercial products. To support this important work and foster Canada’s leadership in stem cell research, Budget 2019 proposes to provide the Stem Cell Network with renewed funding of $18 million over three years, starting in 2019–20.

…

Genome Canada: The insights derived from genomics—the study of the entire genetic information of living things encoded in their DNA and related molecules and proteins—hold the potential for breakthroughs that can improve the lives of Canadians and drive innovation and economic growth. Genome Canada is a not-for-profit organization dedicated to advancing genomics science and technology in order to create economic and social benefits for Canadians. To support Genome Canada’s operations, Budget 2019 proposes to provide Genome Canada with $100.5 million over five years, starting in 2020–21. This investment will also enable Genome Canada to launch new large-scale research competitions and projects, in collaboration with external partners, ensuring that Canada’s research community continues to have access to the resources needed to make transformative scientific breakthroughs and translate these discoveries into real-world applications.

…

Years ago, I managed to find a webpage with all of the proposals various organizations were submitting to a government budget committee. It was eye-opening. You can tell which organizations were able to hire someone who knew the current government buzzwords and the things that a government bureaucrat would want to hear and the organizations that didn’t.

Of course, if the government of the day is adamantly against or uninterested, no amount of persusasion will work to get your organization more money in the budget.

Finally

Reluctantly, I am inclined to explore the topic of emerging technologies such as gene-editing not only in the field of agriculture (for gene-editing of plants, fish, and animals see my November 28, 2018 posting) but also with humans. At the very least, it needs to be discussed whether we choose to participate or not.

If you are interested in the arguments against changing Canada’s prohibition against gene-editing of humans, there’s an Ocotber 2, 2017 posting on Impact Ethics by Françoise Baylis, Professor and Canada Research Chair in Bioethics and Philosophy at Dalhousie University, and Alana Cattapan, Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy at the University of Saskatchewan, which makes some compelling arguments. Of course, it was written before the CRISPR twins (my November 28, 2018 posting).

Recaliing CRISPR Therapeutics (mentioned by Gierczak), the company received permission to run clinical trials in the US in October 2018 after the FDA (US Food and Drug Administration) lifted an earlier ban on their trials according to an Oct. 10, 2018 article by Frank Vinhuan for exome,

…

The partners also noted that their therapy is making progress outside of the U.S. They announced that they have received regulatory clearance in “multiple countries” to begin tests of the experimental treatment in both sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia, …

It seems to me that the quotes around “multiple countries” are meant to suggest doubt of some kind. Generally speaking, company representatives make those kinds of generalizations when they’re trying to pump up their copy. E.g., 50% increase in attendance but no whole numbers to tell you what that means. It could mean two people attended the first year and then brought a friend the next year or 100 people attended and the next year there were 150.

Despite attempts to declare personalized medicine as having arrived, I think everything is still in flux with no preordained outcome. The future has yet to be determined but it will be and I , for one, would like to have some say in the matter.