It seems that this new technique for creating wearable electronics will be more like getting a permanent tattoo where the circuits are applied directly to your skin as opposed to being like a temporary tattoo where the circuits are printed onto a substrate and then applied to then, worn on your skin.

An Oct. 14, 2020 American Chemical Society (ACS) news release (also on EurekAlert) announced this latest development in wearable electronics,

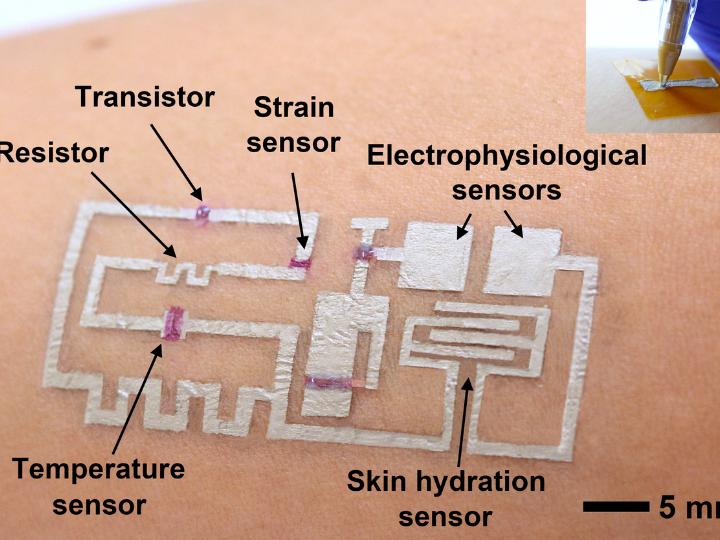

Wearable electronics are getting smaller, more comfortable and increasingly capable of interfacing with the human body. To achieve a truly seamless integration, electronics could someday be printed directly on people’s skin. As a step toward this goal, researchers reporting in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces have safely placed wearable circuits directly onto the surface of human skin to monitor health indicators, such as temperature, blood oxygen, heart rate and blood pressure.

The latest generation of wearable electronics for health monitoring combines soft on-body sensors with flexible printed circuit boards (FPCBs) for signal readout and wireless transmission to health care workers. However, before the sensor is attached to the body, it must be printed or lithographed onto a carrier material, which can involve sophisticated fabrication approaches. To simplify the process and improve the performance of the devices, Peng He, Weiwei Zhao, Huanyu Cheng and colleagues wanted to develop a room-temperature method to sinter metal nanoparticles onto paper or fabric for FPCBs and directly onto human skin for on-body sensors. Sintering — the process of fusing metal or other particles together — usually requires heat, which wouldn’t be suitable for attaching circuits directly to skin.

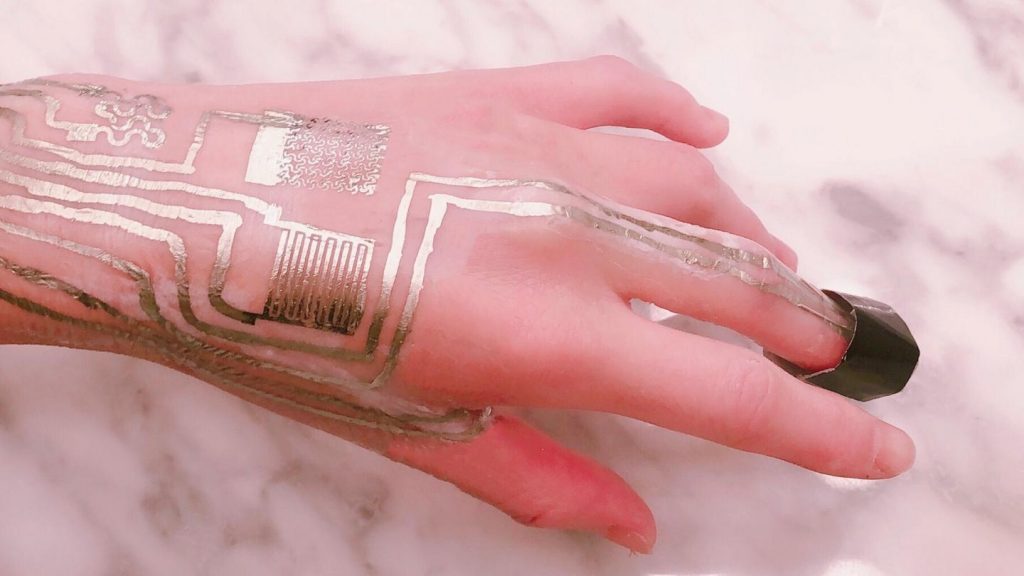

The researchers designed an electronic health monitoring system that consisted of sensor circuits printed directly on the back of a human hand, as well as a paper-based FPCB attached to the inside of a shirt sleeve. To make the FPCB part of the system, the researchers coated a piece of paper with a novel sintering aid and used an inkjet printer with silver nanoparticle ink to print circuits onto the coating. As solvent evaporated from the ink, the silver nanoparticles sintered at room temperature to form circuits. A commercially available chip was added to wirelessly transmit the data, and the resulting FPCB was attached to a volunteer’s sleeve. The team used the same process to sinter circuits on the volunteer’s hand, except printing was done with a polymer stamp. As a proof of concept, the researchers made a full electronic health monitoring system that sensed temperature, humidity, blood oxygen, heart rate, blood pressure and electrophysiological signals and analyzed its performance. The signals obtained by these sensors were comparable to or better than those measured by conventional commercial devices.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Wearable Circuits Sintered at Room Temperature Directly on the Skin Surface for Health Monitoring by Ling Zhang, Hongjun Ji, Houbing Huang, Ning Yi, Xiaoming Shi, Senpei Xie, Yaoyin Li, Ziheng Ye, Pengdong Feng, Tiesong Lin, Xiangli Liu, Xuesong Leng, Mingyu Li, Jiaheng Zhang, Xing Ma, Peng He, Weiwei Zhao, and Huanyu Cheng. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 40, 45504–45515 Publication Date:September 11, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.0c11479 Copyright © 2020 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.