Nice to learn of this news, which is on the CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) news online website. From a December 13, 2022 news item provided by Associated Press (Note: the news item was updated to include general description and some Canadian content at about 12 pm PT) ,

…

Researchers at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California for the first time produced more energy in a fusion reaction than was used to ignite it, [emphasis mine] something called net energy gain, the Energy Department said.

…

Peter Behr’s December 13, 2022 article on Politico.com about the US Department of Energy’s big announcement also breaks the news,

The Department of Energy announced Tuesday [December 12, 2022] that its scientists have produced the first ever fusion reaction that yielded more energy than the reaction required, an essential step in the long path toward commercial fusion power, officials said.

The experiment Dec. 5 [2022], at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, took a few billionths of second. But laboratory leaders said today that it demonstrated for the first time that sustained fusion power is possible.

…

Behr explains what nuclear fusion is but first he touches on why scientists are so interested in the process, from his December 13, 2022 article,

…

In theory, nuclear fusion could produce massive amounts of energy without producing lost-lasting radioactive waste, or posing the risk of meltdowns. That’s unlike nuclear fission, which powers today’s reactors.

Fission results when radioactive atoms — most commonly uranium — are split by neutrons in controlled chain reactions, creating lighter atoms and large amounts of radiation and energy to produce electric power.

Fusion is the opposite process. In the most common approach, swirling hydrogen isotopes are forced together under tremendous heat to create helium and energy for power generation. This is the same process that powers the sun and other stars. But scientists have been trying since the mid-20th century to find a way to use it to generate power on Earth.

…

There are two main approaches to making fusion happen and I found a description for them in an October 2022 article about local company, General Fusion, by Nelson Bennett for Business in Vancouver magazine (paper version),

Most fusion companies are pursuing one of two approaches: Magnet [sic] or inertial confinement. General fusion is one of the few that is taking a more hybrid approach ¬ magnetic confinement with pulse compression.

Fusion occurs when smaller nuclei are fused together under tremendous force into larger nuclei, with a release of energy occurring in the form of neutrons. It’s what happens to stars when gravitational force creates extreme heat that turns on the fusion engine.

Replicating that in a machine requires some form of confinement to squeeze plasma ¬ a kind of super-hot fog of unbound positive and negative particles ¬ to the point where nuclei fuse.

One approach is inertial confinement, in which lasers are focused on a small capsule of heavy hydrogen fuel (deuterium and tritium) to create ignition. This takes a tremendous amount of energy, and the challenge for all fusion efforts is to get a sustained ignition that produces more energy than it takes to get ignition ¬ called net energy gain.

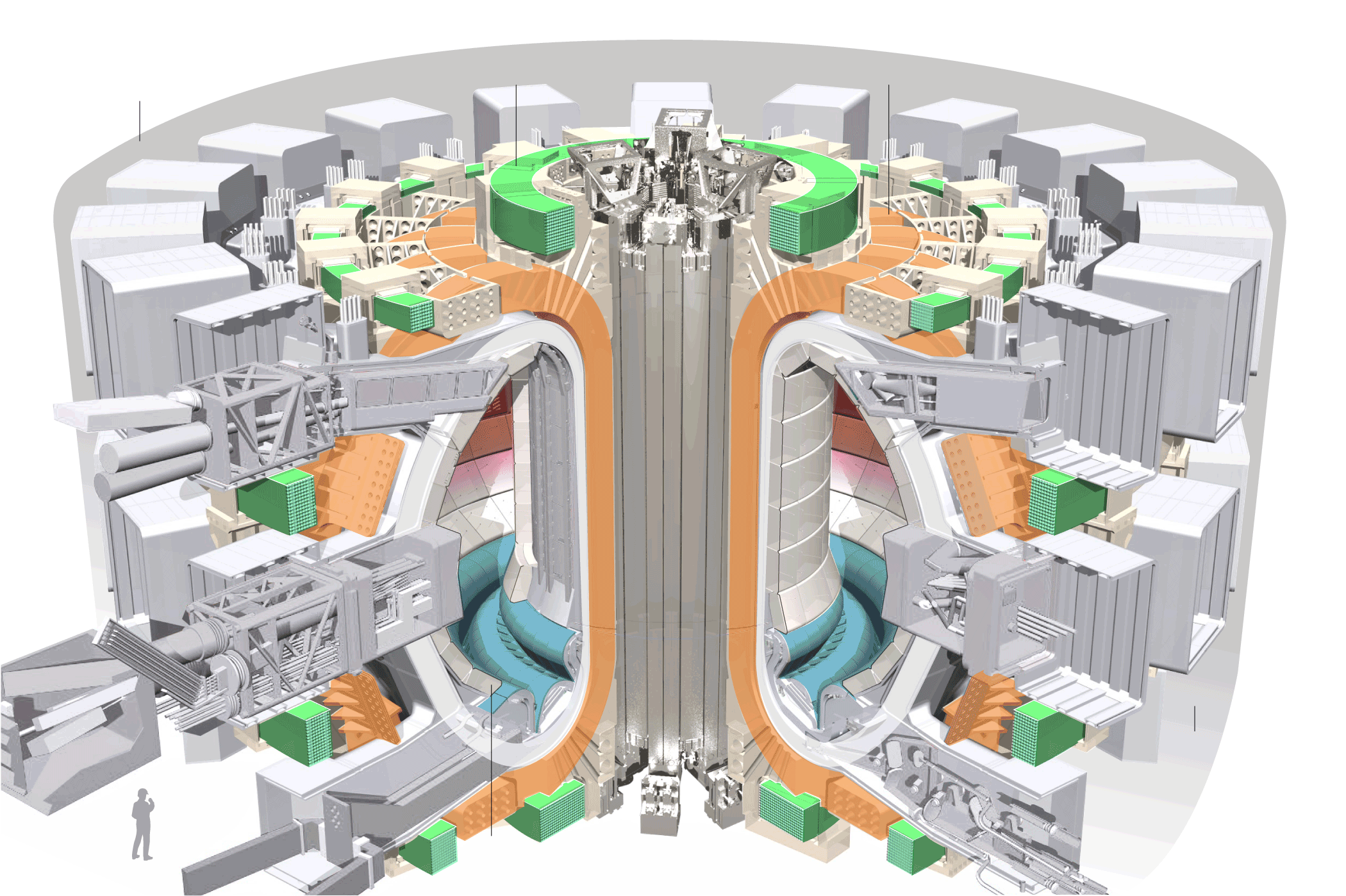

The other main approach is magnetic confinement, using powerful magnets in a machine called a tokomak to contain and squeeze plasma into a donut-shaped form called a torus.

General Fusion uses magnets to confine the plasma, but to get ignition it uses pistons arrayed around a spherical chamber to fire synchronously to essentially collapse the plasma on itself and spark ignition.

General Fusion’s machine uses liquid metal spinning inside a chamber that acts as a protective barrier between the hot plasma and the machine ¬ basically a sphere of plasma contained within a sphere of liquid metal. This protects the machine from damage.

The temperatures generated in fusion ¬ up to to 150 million degrees Celsius ¬ are five to six times hotter than the core of the sun, and can destroy machines that produce them. This makes durability a big challenge in any machine.

…

The Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) issued a December 13, 2022 news release, which provides more detail about their pioneering work, Note: I have changed the order of the paragraphs but all of this is from the news release,

…

Fusion is the process by which two light nuclei combine to form a single heavier nucleus, releasing a large amount of energy. In the 1960s, a group of pioneering scientists at LLNL hypothesized that lasers could be used to induce fusion in a laboratory setting. Led by physicist John Nuckolls, who later served as LLNL director from 1988 to 1994, this revolutionary idea became inertial confinement fusion, kicking off more than 60 years of research and development in lasers, optics, diagnostics, target fabrication, computer modeling and simulation and experimental design.

To pursue this concept, LLNL built a series of increasingly powerful laser systems, leading to the creation of NIF [National Ignition Facility], the world’s largest and most energetic laser system. NIF — located at LLNL in Livermore, California — is the size of a sports stadium and uses powerful laser beams to create temperatures and pressures like those in the cores of stars and giant planets, and inside exploding nuclear weapons.

…

LLNL’s experiment surpassed the fusion threshold by delivering 2.05 megajoules (MJ) of energy to the target, resulting in 3.15 MJ of fusion energy output, demonstrating for the first time a most fundamental science basis for inertial fusion energy (IFE). Many advanced science and technology developments are still needed to achieve simple, affordable IFE to power homes and businesses, and DOE is currently restarting a broad-based, coordinated IFE program in the United States. Combined with private-sector investment, there is a lot of momentum to drive rapid progress toward fusion commercialization.

If you want to see some really excited comments from scientists just read the LLNL’s December 13, 2022 news release. Even the news release’s banner is exuberant,

Behr peers into the future of fusion energy, from his December 13, 2022 article,

Fearful that China might wind up dominating fusion energy in the second half of this century, Congress in 2020 told DOE [Department of Energy] to begin funding development of a utility-scale fusion pilot plant that could deliver at least 50 megawatts of power to the U.S. grid.

…

In September [2022], DOE invited private companies to apply for an initial $50 million in research grants to help fund development of detailed pilot plant plans.

“We’re seeking strong partnerships between DOE and the private sector,” a senior DOE official told POLITICO’s E&E News recently. The official was not willing to speak on the record, saying the grant process is ongoing and confidential.

As the competition proceeds, DOE will set technical milestones or requirements, challenging the teams to show how critical engineering challenges will be overcome. DOE’s goal is “hopefully to enable a fusion pilot to operate in the early 2030s,” the official added.

At least 15 U.S. and foreign fusion companies have submitted requests for an initial total of $50 million in pilot plant grants, and some of them are pursuing the laser-ignition fusion process that Lawrence Livermore has pioneered, said Holland. He did not name the companies because the competition is confidential.

…

I wonder if General Fusion whose CEO (Chief Executive Officer) Greg Twinney declared, “Commercializing fusion energy is within reach, and General Fusion is ready to deliver it to the grid by the 2030s …” (in a December 12, 2022 company press release) is part of the US competition.

I noticed that General Fusion lists this at the end of the press release,

… Founded in 2002, we are headquartered in Vancouver, Canada, with additional centers co-located with internationally recognized fusion research laboratories near London, U.K., and Oak Ridge, Tennessee, U.S.A.

The Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), like the LLNL, is a US Department of Energy research facility.

As for General Fusion’s London connection, I have more about that in my October 28, 2022 posting “Overview of fusion energy scene,” which includes General Fusion’s then latest news about a commercialization agreement with the UKAEA (UK Atomic Energy Authority) and a ‘fusion’ video by rapper Baba Brinkman along with the overview.