The molds for the framework were knitted and filled with ‘mycocrete’ according to a July 14, 2023 Frontiers (Pub.) press release by Angharad Brewer Gillham (also on EurekAlert and published July 17, 2023 on the Newcastle University website),

Scientists hoping to reduce the environmental impact of the construction industry have developed a way to grow building materials using knitted molds and the root network of fungi. Although researchers have experimented with similar composites before, the shape and growth constraints of the organic material have made it hard to develop diverse applications that fulfil its potential. Using the knitted molds as a flexible framework or ‘formwork’, the scientists created a composite called ‘mycocrete’ which is stronger and more versatile in terms of shape and form, allowing the scientists to grow lightweight and relatively eco-friendly construction materials.

“Our ambition is to transform the look, feel and wellbeing of architectural spaces using mycelium in combination with biobased materials such as wool, sawdust and cellulose,” said Dr Jane Scott of Newcastle University [UK], corresponding author of the paper in Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. The research was carried out by a team of designers, engineers, and scientists in the Living Textiles Research Group, part of the Hub for Biotechnology in the Built Environment at Newcastle University, which is funded by Research England.

Root networks

To make composites using mycelium, part of the root network of fungi, scientists mix mycelium spores with grains they can feed on and material that they can grow on. This mixture is packed into a mold and placed in a dark, humid, and warm environment so that the mycelium can grow, binding the substrate tightly together. Once it’s reached the right density, but before it starts to produce the fruiting bodies we call mushrooms, it is dried out. This process could provide a cheap, sustainable replacement for foam, timber, and plastic. But mycelium needs oxygen to grow, which constrains the size and shape of conventional rigid molds and limits current applications.

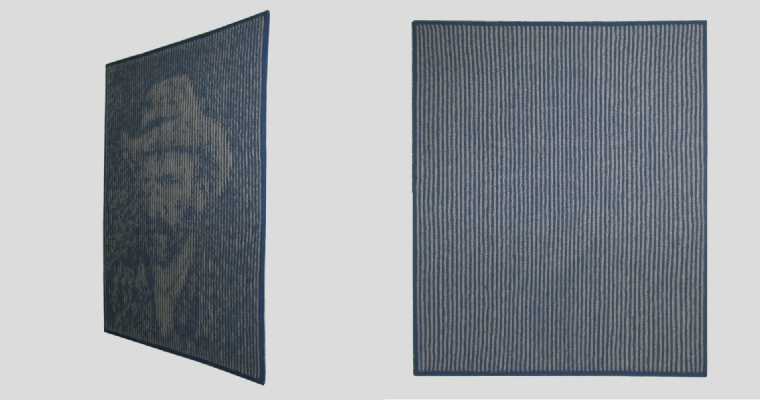

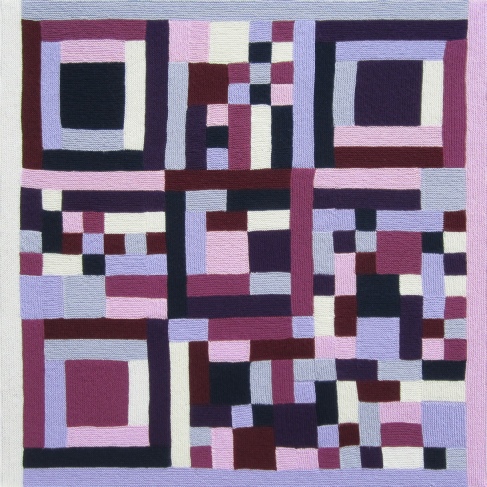

Knitted textiles offer a possible solution: oxygen-permeable molds that could change from flexible to stiff with the growth of the mycelium. But textiles can be too yielding, and it is difficult to pack the molds consistently. Scott and her colleagues set out to design a mycelium mixture and a production system that could exploit the potential of knitted forms.

“Knitting is an incredibly versatile 3D manufacturing system,” said Scott. “It is lightweight, flexible, and formable. The major advantage of knitting technology compared to other textile processes is the ability to knit 3D structures and forms with no seams and no waste.”

Samples of conventional mycelium composite were prepared by the scientists as controls, and grown alongside samples of mycocrete, which also contained paper powder, paper fiber clumps, water, glycerin, and xanthan gum. This paste was designed to be delivered into the knitted formwork with an injection gun to improve packing consistency: the paste needed to be liquid enough for the delivery system, but not so liquid that it failed to hold its shape.

Tubes for their planned test structure were knitted from merino yarn, sterilized, and fixed to a rigid structure while they were filled with the paste, so that changes in tension of the fabric would not affect the performance of the mycocrete.

Building the future

Once dried, samples were subjected to strength tests in tension, compression and flexion. The mycocrete samples proved to be stronger than the conventional mycelium composite samples and outperformed mycelium composites grown without knitted formwork. In addition, the porous knitted fabric of the formwork provided better oxygen availability, and the samples grown in it shrank less than most mycelium composite materials do when they are dried, suggesting more predictable and consistent manufacturing results could be achieved.

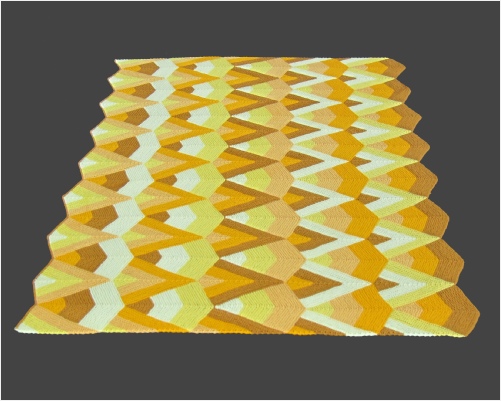

The team were also able to build a larger proof-of-concept prototype structure called BioKnit – a complex freestanding dome constructed in a single piece without joins that could prove to be weak points, thanks to the flexible knitted form.

“The mechanical performance of the mycocrete used in combination with permanent knitted formwork is a significant result, and a step towards the use of mycelium and textile biohybrids within construction,” said Scott. “In this paper we have specified particular yarns, substrates, and mycelium necessary to achieve a specific goal. However, there is extensive opportunity to adapt this formulation for different applications. Biofabricated architecture may require new machine technology to move textiles into the construction sector.”

The mycelium vault (also pictured above) is a freestanding structure,

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

BioKnit: development of mycellium paste for use with permanent textile formwork by Romy Kaiser, Ben Bridgens, Elise Elsacker, Jane Scott. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol., 14 July 2023 Volume 11 – 2023 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2023.1229693

This paper appears to be open access.