Once you get past the technical language (there’s a lot of it), you’ll find that they make the link between biomimicry and memristors explicit. Admittedly I’m not an expert but if I understand the research correctly, the scientists are suggesting that the algorithms used in machine learning today cannot allow memristors to be properly integrated for use in true neuromorphic computing and this work from Russia and Greece points to a new paradigm. If you understand it differently, please do let me know in the comments.

A July 12, 2019 news item on Nanowerk kicks things off (Note: A link has been removed),

Lobachevsky University scientists together with their colleagues from the National Research Center “Kurchatov Institute” (Moscow) and the National Research Center “Demokritos” (Athens) are working on the hardware implementation of a spiking neural network based on memristors.

The key elements of such a network, along with pulsed neurons, are artificial synaptic connections that can change the strength (weight) of connection between neurons during the learning (Microelectronic Engineering, “Yttria-stabilized zirconia cross-point memristive devices for neuromorphic applications”).

For this purpose, memristive devices based on metal-oxide-metal nanostructures developed at the UNN Physics and Technology Research Institute (PTRI) are suitable, but their use in specific spiking neural network architectures developed at the Kurchatov Institute requires demonstration of biologically plausible learning principles.

…

A July 12, 2019 (?) Lobachevsky University press release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, delves further into the work,

The biological mechanism of learning of neural systems is described by Hebb’s rule, according to which learning occurs as a result of an increase in the strength of connection (synaptic weight) between simultaneously active neurons, which indicates the presence of a causal relationship in their excitation. One of the clarifying forms of this fundamental rule is plasticity, which depends on the time of arrival of pulses (Spike-Timing Dependent Plasticity – STDP).

In accordance with STDP, synaptic weight increases if the postsynaptic neuron generates a pulse (spike) immediately after the presynaptic one, and vice versa, the synaptic weight decreases if the postsynaptic neuron generates a spike right before the presynaptic one. Moreover, the smaller the time difference Δt between the pre- and postsynaptic spikes, the more pronounced the weight change will be.

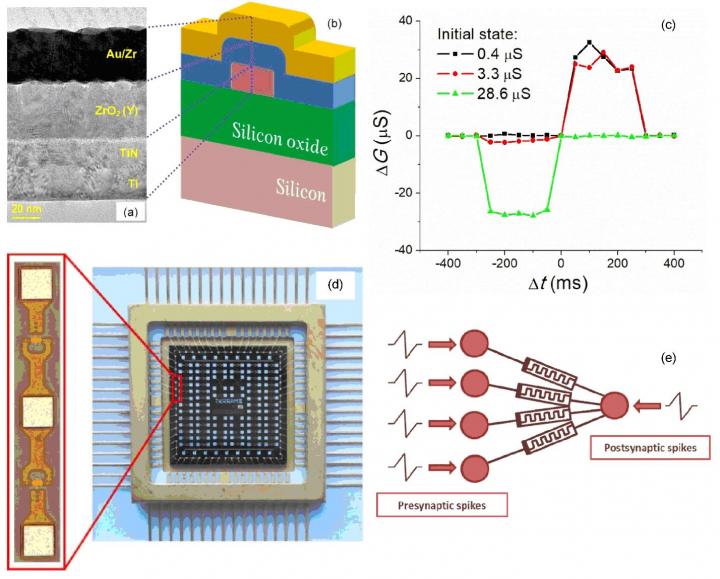

According to one of the researchers, Head of the UNN PTRI laboratory Alexei Mikhailov, in order to demonstrate the STDP principle, memristive nanostructures based on yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) thin films were used. YSZ is a well-known solid-state electrolyte with high oxygen ion mobility.

“Due to a specified concentration of oxygen vacancies, which is determined by the controlled concentration of yttrium impurities, and the heterogeneous structure of the films obtained by magnetron sputtering, such memristive structures demonstrate controlled bipolar switching between different resistive states in a wide resistance range. The switching is associated with the formation and destruction of conductive channels along grain boundaries in the polycrystalline ZrO2 (Y) film,” notes Alexei Mikhailov.

An array of memristive devices for research was implemented in the form of a microchip mounted in a standard cermet casing, which facilitates the integration of the array into a neural network’s analog circuit. The full technological cycle for creating memristive microchips is currently implemented at the UNN PTRI. In the future, it is possible to scale the devices down to the minimum size of about 50 nm, as was established by Greek partners.

Our studies of the dynamic plasticity of the memoristive devices, continues Alexey Mikhailov, have shown that the form of the conductance change depending on Δt is in good agreement with the STDP learning rules. It should be also noted that if the initial value of the memristor conductance is close to the maximum, it is easy to reduce the corresponding weight while it is difficult to enhance it, and in the case of a memristor with a minimum conductance in the initial state, it is difficult to reduce its weight, but it is easy to enhance it.According to Vyacheslav Demin, director-coordinator in the area of nature-like technologies of the Kurchatov Institute, who is one of the ideologues of this work, the established pattern of change in the memristor conductance clearly demonstrates the possibility of hardware implementation of the so-called local learning rules. Such rules for changing the strength of synaptic connections depend only on the values of variables that are present locally at each time point (neuron activities and current weights).

“This essentially distinguishes such principle from the traditional learning algorithm, which is based on global rules for changing weights, using information on the error values at the current time point for each neuron of the output neural network layer (in a widely popular group of error back propagation methods). The traditional principle is not biosimilar, it requires “external” (expert) knowledge of the correct answers for each example presented to the network (that is, they do not have the property of self-learning). This principle is difficult to implement on the basis of memristors, since it requires controlled precise changes of memristor conductances, as opposed to local rules. Such precise control is not always possible due to the natural variability (a wide range of parameters) of memristors as analog elements,” says Vyacheslav Demin.

Local learning rules of the STDP type implemented in hardware on memristors provide the basis for autonomous (“unsupervised”) learning of a spiking neural network. In this case, the final state of the network does not depend on its initial state, but depends only on the learning conditions (a specific sequence of pulses). According to Vyacheslav Demin, this opens up prospects for the application of local learning rules based on memristors when solving artificial intelligence problems with the use of complex spiking neural network architectures.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Yttria-stabilized zirconia cross-point memristive devices for neuromorphic applications by A. V. Emelyanov, K. E. Nikiruy, A. Demin, V. V. Rylkov, A. I. Belov, D. S. Korolev, E. G. Gryaznov, D. A. Pavlov, O. N. Gorshkov, A. N. Mikhaylov, P. Dimitrakis. Microelectronic Engineering Volume 215, 15 July 2019, 110988 First available online 16 May 2019

This paper is behind a paywall.