I have a mini roundup of items (3) concerning nanotechnology and environmental applications with a special focus on carbon materials.

Carbon-capturing motors

First up, there’s a Sept. 23, 2015 news item on ScienceDaily which describes work with tiny carbon-capturing motors,

Machines that are much smaller than the width of a human hair could one day help clean up carbon dioxide pollution in the oceans. Nanoengineers at the University of California, San Diego have designed enzyme-functionalized micromotors that rapidly zoom around in water, remove carbon dioxide and convert it into a usable solid form.

The proof of concept study represents a promising route to mitigate the buildup of carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas in the environment, said researchers. …

A Sept 22, 2015 University of California at San Diego (UCSD) news release by Liezel Labios, which originated the news release, provides more details about the scientists’ hopes and the technology,

“We’re excited about the possibility of using these micromotors to combat ocean acidification and global warming,” said Virendra V. Singh, a postdoctoral scientist in Wang’s [nanoengineering professor and chair Joseph Wang] research group and a co-first author of this study.

In their experiments, nanoengineers demonstrated that the micromotors rapidly decarbonated water solutions that were saturated with carbon dioxide. Within five minutes, the micromotors removed 90 percent of the carbon dioxide from a solution of deionized water. The micromotors were just as effective in a sea water solution and removed 88 percent of the carbon dioxide in the same timeframe.

“In the future, we could potentially use these micromotors as part of a water treatment system, like a water decarbonation plant,” said Kevin Kaufmann, an undergraduate researcher in Wang’s lab and a co-author of the study.

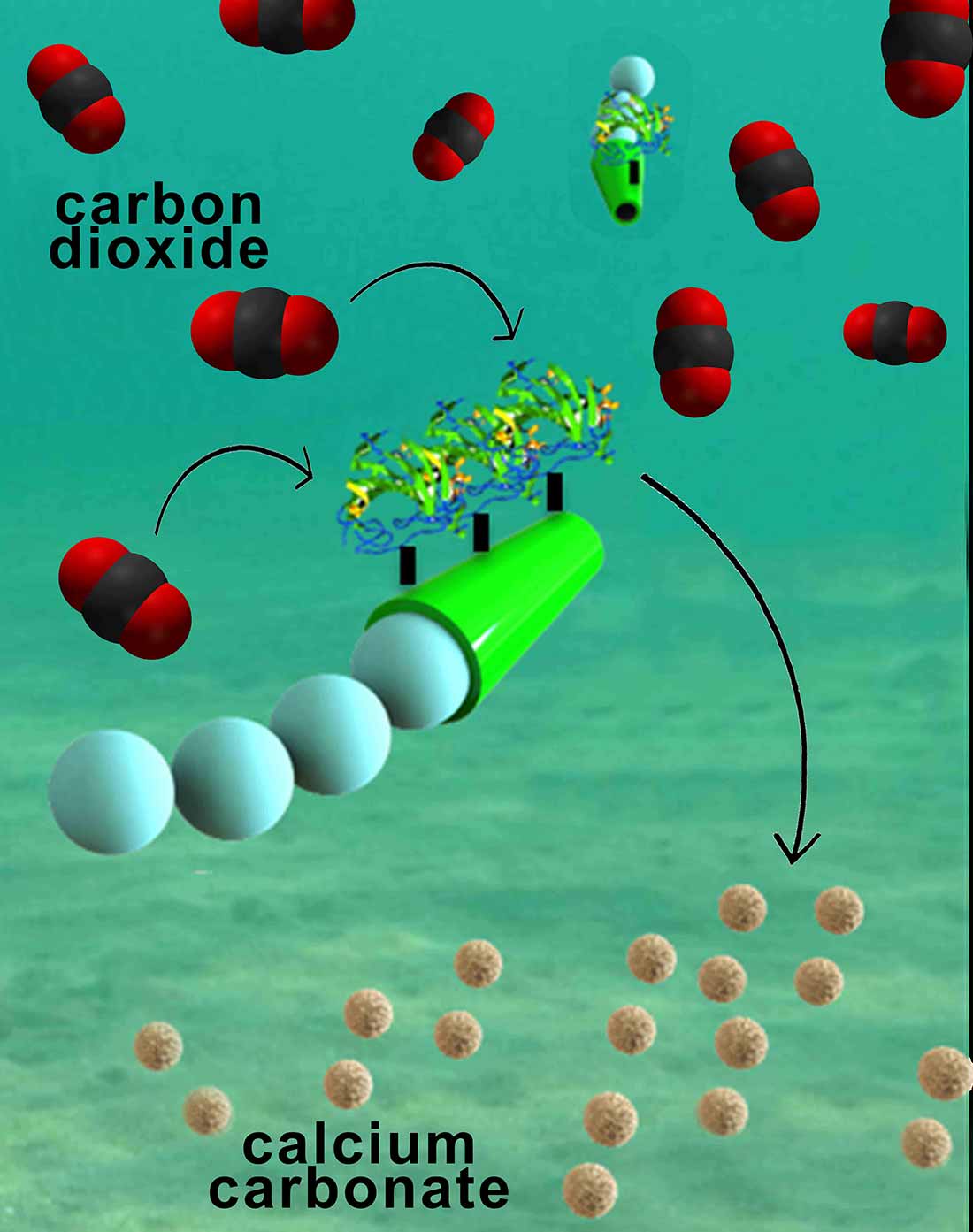

The micromotors are essentially six-micrometer-long tubes that help rapidly convert carbon dioxide into calcium carbonate, a solid mineral found in eggshells, the shells of various marine organisms, calcium supplements and cement. The micromotors have an outer polymer surface that holds the enzyme carbonic anhydrase, which speeds up the reaction between carbon dioxide and water to form bicarbonate. Calcium chloride, which is added to the water solutions, helps convert bicarbonate to calcium carbonate.

The fast and continuous motion of the micromotors in solution makes the micromotors extremely efficient at removing carbon dioxide from water, said researchers. The team explained that the micromotors’ autonomous movement induces efficient solution mixing, leading to faster carbon dioxide conversion. To fuel the micromotors in water, researchers added hydrogen peroxide, which reacts with the inner platinum surface of the micromotors to generate a stream of oxygen gas bubbles that propel the micromotors around. When released in water solutions containing as little as two to four percent hydrogen peroxide, the micromotors reached speeds of more than 100 micrometers per second.

However, the use of hydrogen peroxide as the micromotor fuel is a drawback because it is an extra additive and requires the use of expensive platinum materials to build the micromotors. As a next step, researchers are planning to make carbon-capturing micromotors that can be propelled by water.

“If the micromotors can use the environment as fuel, they will be more scalable, environmentally friendly and less expensive,” said Kaufmann.

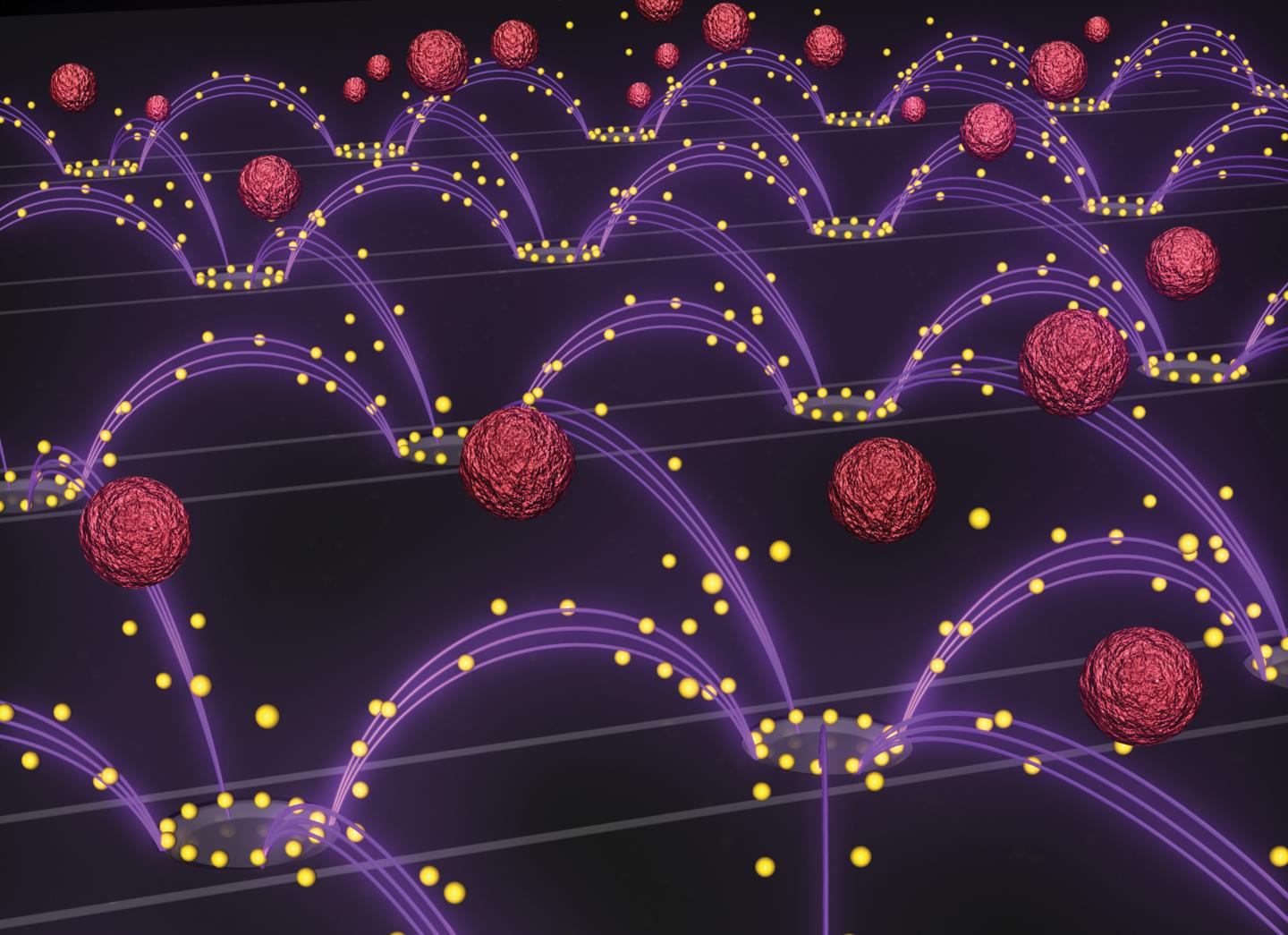

The researchers have provided an image which illustrates the carbon-capturing motors in action,

Nanoengineers have invented tiny tube-shaped micromotors that zoom around in water and efficiently remove carbon dioxide. The surfaces of the micromotors are functionalized with the enzyme carbonic anhydrase, which enables the motors to help rapidly convert carbon dioxide to calcium carbonate. Image credit: Laboratory for Nanobioelectronics, UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Micromotor-Based Biomimetic Carbon Dioxide Sequestration: Towards Mobile Microscrubbers by Murat Uygun, Virendra V. Singh, Kevin Kaufmann, Deniz A. Uygun, Severina D. S. de Oliveira, and oseph Wang. Angewandte Chemie DOI: 10.1002/ange.201505155 Article first published online: 4 SEP 2015

© 2015 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim

This article is behind a paywall.

Carbon nanotubes for carbon dioxide capture (carbon capture)

In a Sept. 22, 2015 posting by Dexter Johnson on his Nanoclast blog (located on the IEEE [Institute for Electrical and Electronics Engineers] website) describes research where carbon nanotubes are being used for carbon capture,

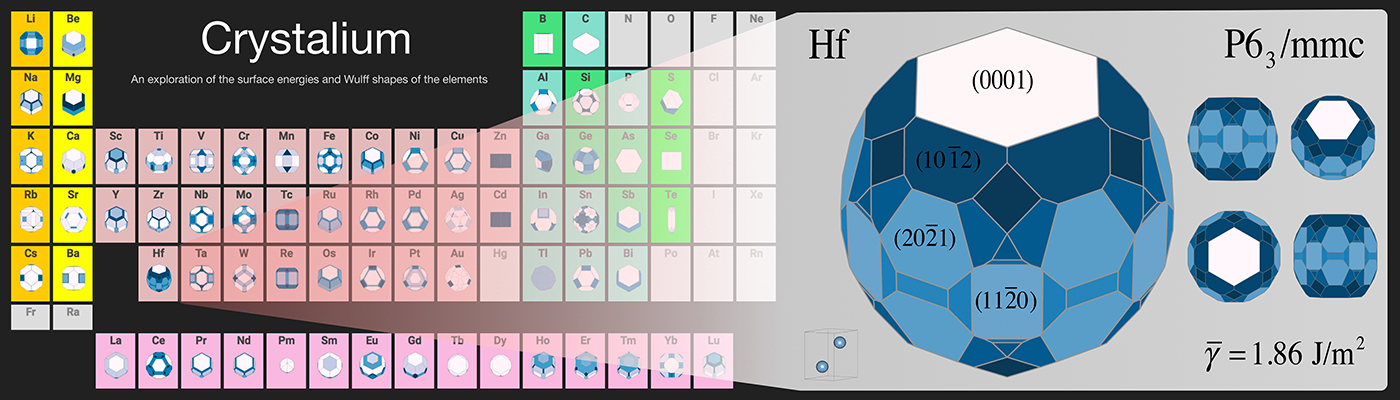

Now researchers at Technische Universität Darmstadt in Germany and the Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur have found that they can tailor the gas adsorption properties of vertically aligned carbon nanotubes (VACNTs) by altering their thickness, height, and the distance between them.

“These parameters are fundamental for ‘tuning’ the hierarchical pore structure of the VACNTs,” explained Mahshid Rahimi and Deepu Babu, doctoral students at the Technische Universität Darmstadt who were the paper’s lead authors, in a press release. “This hierarchy effect is a crucial factor for getting high-adsorption capacities as well as mass transport into the nanostructure. Surprisingly, from theory and by experiment, we found that the distance between nanotubes plays a much larger role in gas adsorption than the tube diameter does.”

Dexter provides a good and brief summary of the research.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Double-walled carbon nanotube array for CO2 and SO2 adsorption by Mahshid Rahimi, Deepu J. Babu, Jayant K. Singh, Yong-Biao Yang, Jörg J. Schneider, and Florian Müller-Plathe. J. Chem. Phys. 143, 124701 (2015); http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4929609

This paper is open access.

The market for nanotechnology-enabled environmental applications

Coincident with stumbling across these two possible capture solutions, I found this Sept. 23, 2015 BCC Research news release,

A groundswell of global support for developing nanotechnology as a pollution remediation technique will continue for the foreseeable future. BCC Research reveals in its new report that this key driver, along with increasing worldwide concerns over removing pollutants and developing alternative energy sources, will drive growth in the nanotechnology environmental applications market.

The global nanotechnology market in environmental applications is expected to reach $25.7 billion by 2015 and $41.8 billion by 2020, conforming to a five-year (2015-2020) compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.2%. Air remediation as a segment will reach $10.2 billion and $16.7 billion in 2015 and 2020, respectively, reflecting a five-year CAGR of 10.3%. Water remediation as a segment will grow at a five-year CAGR of 12.4% to reach $10.6 billion in 2020.

…

As nanoparticles push the limits and capabilities of technology, new and better techniques for pollution control are emerging. Presently, nanotechnology’s greatest potential lies in air pollution remediation.

“Nano filters could be applied to automobile tailpipes and factory smokestacks to separate out contaminants and prevent them from entering the atmosphere. In addition, nano sensors have been developed to sense toxic gas leaks at extremely low concentrations,” says BCC research analyst Aneesh Kumar. “Overall, there is a multitude of promising environmental applications for nanotechnology, with the main focus area on energy and water technologies.”

You can find links to the report, TOC (table of contents), and report overview on the BCC Research Nanotechnology in Environmental Applications: The Global Market report webpage.

![Cobalt Blue Tarantula [downloaded from http://www.tarantulaguide.com/tarantula-pictures/cobalt-blue-tarantula-4/]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/CobaltBlueTarantula.jpg)