Turning water into fuel may seem like an almost biblical project (e.g., Jesus turning water to wine in the New Testament) but scientists at Indiana University are hopeful they are halfway to their goal. From a Jan. 4, 2016 news item on ScienceDaily,

Scientists at Indiana University have created a highly efficient biomaterial that catalyzes the formation of hydrogen — one half of the “holy grail” of splitting H2O to make hydrogen and oxygen for fueling cheap and efficient cars that run on water.

A Jan. 4, 2016 Indiana University (IU) news release (also on EurekAlert*), which originated the news item, explains further (Note: Links have been removed),

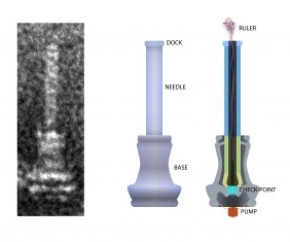

A modified enzyme that gains strength from being protected within the protein shell — or “capsid” — of a bacterial virus, this new material is 150 times more efficient than the unaltered form of the enzyme.

…

“Essentially, we’ve taken a virus’s ability to self-assemble myriad genetic building blocks and incorporated a very fragile and sensitive enzyme with the remarkable property of taking in protons and spitting out hydrogen gas,” said Trevor Douglas, the Earl Blough Professor of Chemistry in the IU Bloomington College of Arts and Sciences’ Department of Chemistry, who led the study. “The end result is a virus-like particle that behaves the same as a highly sophisticated material that catalyzes the production of hydrogen.”

…

The genetic material used to create the enzyme, hydrogenase, is produced by two genes from the common bacteria Escherichia coli, inserted inside the protective capsid using methods previously developed by these IU scientists. The genes, hyaA and hyaB, are two genes in E. coli that encode key subunits of the hydrogenase enzyme. The capsid comes from the bacterial virus known as bacteriophage P22.

The resulting biomaterial, called “P22-Hyd,” is not only more efficient than the unaltered enzyme but also is produced through a simple fermentation process at room temperature.

The material is potentially far less expensive and more environmentally friendly to produce than other materials currently used to create fuel cells. The costly and rare metal platinum, for example, is commonly used to catalyze hydrogen as fuel in products such as high-end concept cars.

“This material is comparable to platinum, except it’s truly renewable,” Douglas said. “You don’t need to mine it; you can create it at room temperature on a massive scale using fermentation technology; it’s biodegradable. It’s a very green process to make a very high-end sustainable material.”

In addition, P22-Hyd both breaks the chemical bonds of water to create hydrogen and also works in reverse to recombine hydrogen and oxygen to generate power. “The reaction runs both ways — it can be used either as a hydrogen production catalyst or as a fuel cell catalyst,” Douglas said.

The form of hydrogenase is one of three occurring in nature: di-iron (FeFe)-, iron-only (Fe-only)- and nitrogen-iron (NiFe)-hydrogenase. The third form was selected for the new material due to its ability to easily integrate into biomaterials and tolerate exposure to oxygen.

NiFe-hydrogenase also gains significantly greater resistance upon encapsulation to breakdown from chemicals in the environment, and it retains the ability to catalyze at room temperature. Unaltered NiFe-hydrogenase, by contrast, is highly susceptible to destruction from chemicals in the environment and breaks down at temperatures above room temperature — both of which make the unprotected enzyme a poor choice for use in manufacturing and commercial products such as cars.

These sensitivities are “some of the key reasons enzymes haven’t previously lived up to their promise in technology,” Douglas said. Another is their difficulty to produce.

“No one’s ever had a way to create a large enough amount of this hydrogenase despite its incredible potential for biofuel production. But now we’ve got a method to stabilize and produce high quantities of the material — and enormous increases in efficiency,” he said.

The development is highly significant according to Seung-Wuk Lee, professor of bioengineering at the University of California-Berkeley, who was not a part of the study.

“Douglas’ group has been leading protein- or virus-based nanomaterial development for the last two decades. This is a new pioneering work to produce green and clean fuels to tackle the real-world energy problem that we face today and make an immediate impact in our life in the near future,” said Lee, whose work has been cited in a U.S. Congressional report on the use of viruses in manufacturing.

Beyond the new study, Douglas and his colleagues continue to craft P22-Hyd into an ideal ingredient for hydrogen power by investigating ways to activate a catalytic reaction with sunlight, as opposed to introducing elections using laboratory methods.

“Incorporating this material into a solar-powered system is the next step,” Douglas said.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Self-assembling biomolecular catalysts for hydrogen production by Paul C. Jordan, Dustin P. Patterson, Kendall N. Saboda, Ethan J. Edwards, Heini M. Miettinen, Gautam Basu, Megan C. Thielges, & Trevor Douglas. Nature Chemistry (2015) doi:10.1038/nchem.2416 Published online 21 December 2015

This paper is behind a paywall.

*(also on EurekAlert) added on Jan. 5, 2016 at 1550 PST.