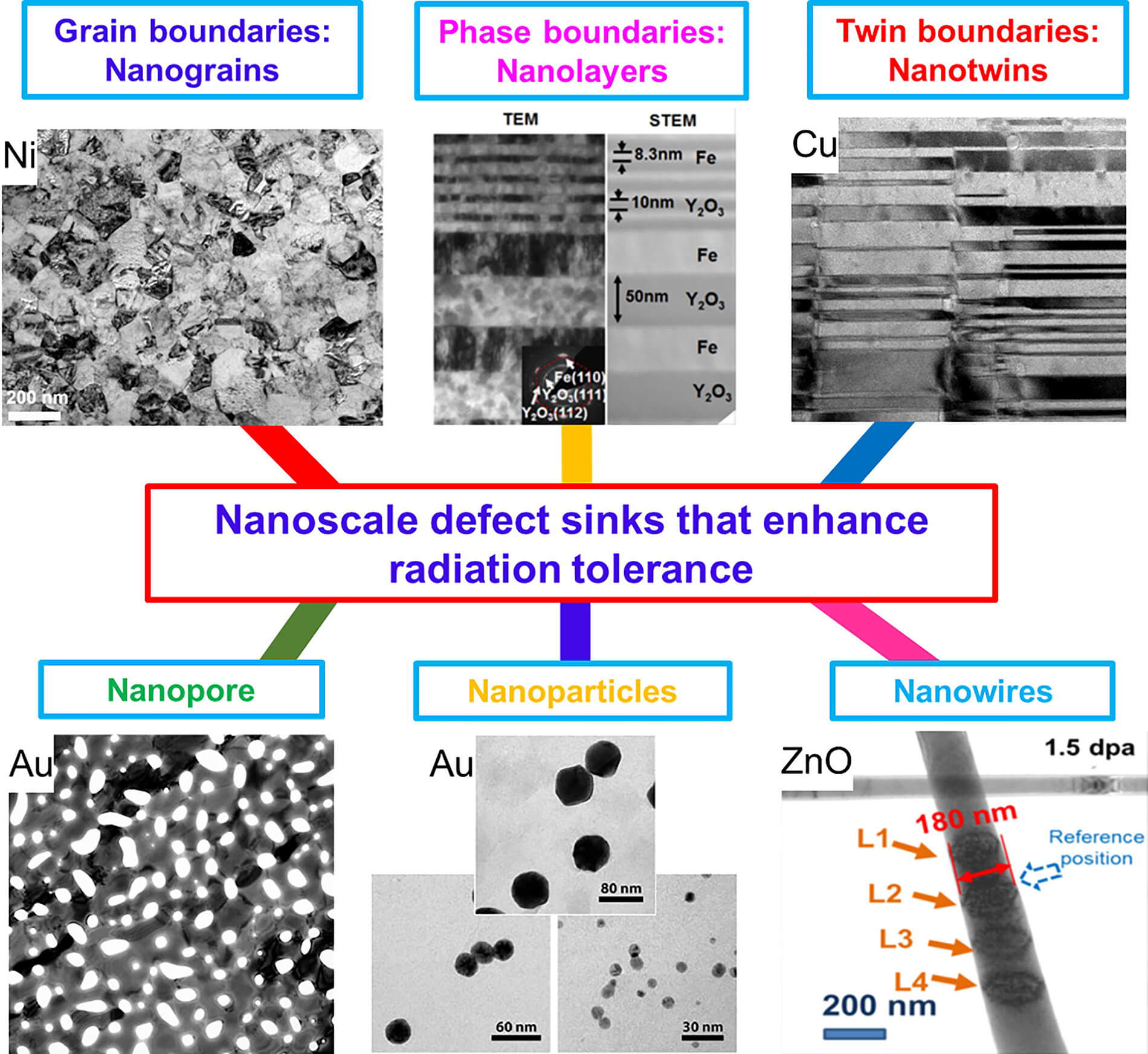

This high-resolution transmission electron micrograph of particles made by the research team shows the particles’ highly uniform size and shape. These are iron oxide particles just 3 nanometers across, coated with a zwitterion layer. Their small size means they can easily be cleared through the kidneys after injection. Courtesy of the researchers

A Feb. 14, 2017 news item on ScienceDaily announces a new MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) contrast agent,

A new, specially coated iron oxide nanoparticle developed by a team at MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology] and elsewhere could provide an alternative to conventional gadolinium-based contrast agents used for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) procedures. In rare cases, the currently used gadolinium agents have been found to produce adverse effects in patients with impaired kidney function.

A Feb. 14, 2017 MIT news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides more technical detail,

The advent of MRI technology, which is used to observe details of specific organs or blood vessels, has been an enormous boon to medical diagnostics over the last few decades. About a third of the 60 million MRI procedures done annually worldwide use contrast-enhancing agents, mostly containing the element gadolinium. While these contrast agents have mostly proven safe over many years of use, some rare but significant side effects have shown up in a very small subset of patients. There may soon be a safer substitute thanks to this new research.

In place of gadolinium-based contrast agents, the researchers have found that they can produce similar MRI contrast with tiny nanoparticles of iron oxide that have been treated with a zwitterion coating. (Zwitterions are molecules that have areas of both positive and negative electrical charges, which cancel out to make them neutral overall.) The findings are being published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, in a paper by Moungi Bawendi, the Lester Wolfe Professor of Chemistry at MIT; He Wei, an MIT postdoc; Oliver Bruns, an MIT research scientist; Michael Kaul at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf in Germany; and 15 others.

Contrast agents, injected into the patient during an MRI procedure and designed to be quickly cleared from the body by the kidneys afterwards, are needed to make fine details of organ structures, blood vessels, and other specific tissues clearly visible in the images. Some agents produce dark areas in the resulting image, while others produce light areas. The primary agents for producing light areas contain gadolinium.

Iron oxide particles have been largely used as negative (dark) contrast agents, but radiologists vastly prefer positive (light) contrast agents such as gadolinium-based agents, as negative contrast can sometimes be difficult to distinguish from certain imaging artifacts and internal bleeding. But while the gadolinium-based agents have become the standard, evidence shows that in some very rare cases they can lead to an untreatable condition called nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, which can be fatal. In addition, evidence now shows that the gadolinium can build up in the brain, and although no effects of this buildup have yet been demonstrated, the FDA is investigating it for potential harm.

“Over the last decade, more and more side effects have come to light” from the gadolinium agents, Bruns says, so that led the research team to search for alternatives. “None of these issues exist for iron oxide,” at least none that have yet been detected, he says.

The key new finding by this team was to combine two existing techniques: making very tiny particles of iron oxide, and attaching certain molecules (called surface ligands) to the outsides of these particles to optimize their characteristics. The iron oxide inorganic core is small enough to produce a pronounced positive contrast in MRI, and the zwitterionic surface ligand, which was recently developed by Wei and coworkers in the Bawendi research group, makes the iron oxide particles water-soluble, compact, and biocompatible.

The combination of a very tiny iron oxide core and an ultrathin ligand shell leads to a total hydrodynamic diameter of 4.7 nanometers, below the 5.5-nanometer renal clearance threshold. This means that the coated iron oxide should quickly clear through the kidneys and not accumulate. This renal clearance property is an important feature where the particles perform comparably to gadolinium-based contrast agents.

Now that initial tests have demonstrated the particles’ effectiveness as contrast agents, Wei and Bruns say the next step will be to do further toxicology testing to show the particles’ safety, and to continue to improve the characteristics of the material. “It’s not perfect. We have more work to do,” Bruns says. But because iron oxide has been used for so long and in so many ways, even as an iron supplement, any negative effects could likely be treated by well-established protocols, the researchers say. If all goes well, the team is considering setting up a startup company to bring the material to production.

For some patients who are currently excluded from getting MRIs because of potential side effects of gadolinium, the new agents “could allow those patients to be eligible again” for the procedure, Bruns says. And, if it does turn out that the accumulation of gadolinium in the brain has negative effects, an overall phase-out of gadolinium for such uses could be needed. “If that turned out to be the case, this could potentially be a complete replacement,” he says.

Ralph Weissleder, a physician at Massachusetts General Hospital who was not involved in this work, says, “The work is of high interest, given the limitations of gadolinium-based contrast agents, which typically have short vascular half-lives and may be contraindicated in renally compromised patients.”

The research team included researchers in MIT’s chemistry, biological engineering, nuclear science and engineering, brain and cognitive sciences, and materials science and engineering departments and its program in Health Sciences and Technology; and at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf; Brown University; and the Massachusetts General Hospital. It was supported by the MIT-Harvard NIH Center for Cancer Nanotechnology, the Army Research Office through MIT’s Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies, the NIH-funded Laser Biomedical Research Center, the MIT Deshpande Center, and the European Union Seventh Framework Program.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Exceedingly small iron oxide nanoparticles as positive MRI contrast agents by He Wei, Oliver T. Bruns, Michael G. Kaul, Eric C. Hansen, Mariya Barch, Agata Wiśniowsk, Ou Chen, Yue Chen, Nan Li, Satoshi Okada, Jose M. Cordero, Markus Heine, Christian T. Farrar, Daniel M. Montana, Gerhard Adam, Harald Ittrich, Alan Jasanoff, Peter Nielsen, and Moungi G. Bawendi. PNAS February 13, 2017 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620145114 Published online before print February 13, 2017

This paper is behind a paywall.