A September 7, 2021 Frontiers news release (also on EurekAlert) describes the company’s latest initiative to engage children in science (Note: I have a bit more about one of the Nobel Laureates, Dan [Daniel] Schechtman at the end of this posting),

Young people everywhere now have access to a free collection of scientific articles written by winners of science’s most coveted honor, the Nobel Prize. The Nobel Collection, published by Frontiers, aims to improve young people’s access to learning material about science’s role in addressing today’s global challenges. The collection will connect young minds with some of today’s most distinguished scientists through engaging learning material steeped in some of the most groundbreaking research from over the last twenty years.

Written for young people aged eight to 15, the collection has been published in the journal Frontiers for Young Minds. With the help of a science mentor, each article in the Nobel Collection has been reviewed by kids themselves to ensure it is understandable, fun, and engaging before publication. By sparking an interest in science from a young age, the Nobel Collection aims to improve young people’s scientific worldview. Its objective is to equip them with a scientific mindset and appreciation of the central role of science in finding solutions to today’s growing catalogue of global challenges.

A keen 13-year-old reviewer from Switzerland shared his experience, “I’m very interested in science and it is fascinating to review papers from the real scientists who know so much about their specialized fields! Many of the papers explain dangerous illnesses to children, and I think such information is so important!”

May-Britt Moser, awarded The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2014, said, “I’m honored to contribute to the journal Frontiers for Young Minds. Children are born curious, with passion for questions and with light in their eyes. As a scientist, I feel privileged to be able to ask questions that I think are important. I hope the papers in this journal may help nurture and reinforce children’s passion and curiosity for science – what a gift to humanity that would be!”

Commenting on the Collection, Aaron Ciechanover who was awarded The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2004, said, “Prizes and recognition are not targets that one should aim for. Breakthrough achievements that expand our knowledge of the world and benefit mankind are. Reading about science was my hobby as a kid and, doubtless, the seed of my curiosity into scientific discovery.”

Currently, the Nobel Collection comprises of contributions including:

How do we find our way? Grid cells in the brain, written by May-Britt Moser, awarded The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2014.

Computer Simulations in Service of Biology, written by Michael Levitt, awarded The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2013.

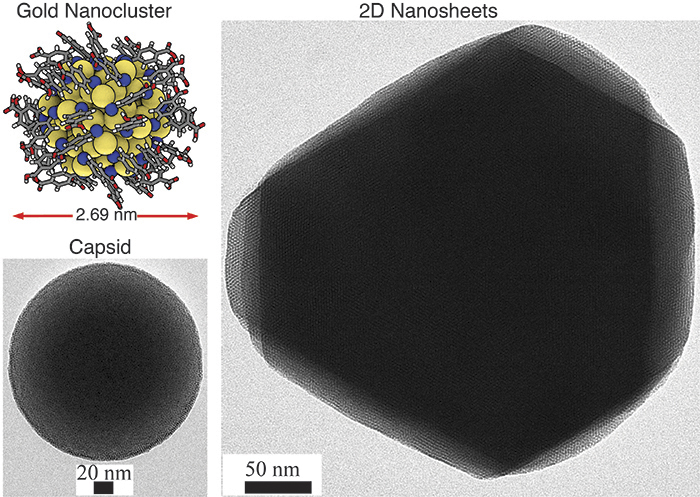

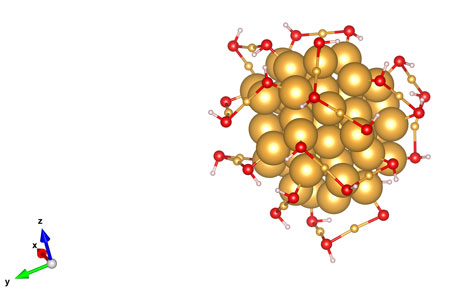

Quasi-Crystal, Not Quasi-Scientist, written by Dan Shechtman, awarded The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2011.

The Transcription of Life: from DNA to RNA, written by Roger D. Kornberg, awarded The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2006.

Targeted Degradation of Proteins – the Ubiquitin System, written by Aaron Ciechanover, The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2004.

The Nobel Collection’s co-editor Idan Segev, professor of computational neuroscience at the Hebrew University, said: “What we want to achieve with this collection, beyond improving kids’ understanding of the scientific process and the particular Nobel recognized breakthroughs, is to acquaint kids with scientific role models – someone for young people to look up to. The beauty of these articles is that the Nobel Laureates share their life experience with kids, their failures and passions, and provide personal advice for the young minds.

“The kids that we worked with to review the articles were amazed by what they were reading and left the classes with a real sense of admiration for the humanistic as well as the scientific facet of Nobel prize winners. It is an incredible learning resource that can be accessed by anyone with an internet connection worldwide, which in context of the disruption created by the COVID-19 pandemic makes it particularly important.”

UN Sustainable Development Goals – Quality Education

The initiative is also part of Frontiers’ commitment to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [SDGs], particularly Goal 4 – Quality Education. Disruption to access to quality education has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially jeopardizing some of the hard-won gains in recent years.

Frontiers, who funds the Frontiers for Young Minds journal as part of its philanthropy program, intends to work with at least five more Nobel Laureates later this year to grow the resource. All the articles are free to read, download, and share. Plans are also in place to translate the Nobel Collection into a portfolio of languages so even more young people from around the world can make use of it.

Dr. Fred Fenter, chief executive editor of Frontiers, said: “From fighting climate change to disease to poverty, science saves lives. What better role models to inspire future generations of scientists than Nobel Prize winners themselves. Our hope is the Nobel Collection will act as a catalyst, both motivating young people and improving their appreciation of the central role science will play in creating a sustainable future for people and planet.”

The Frontiers for Young Minds initiative

The Frontiers for Young Minds journal launched in 2013. Since then, Frontiers has engaged with around 3,500 young reviewers, each of whom has been guided by one of around 600 science mentors. To date, the journal has received more than ten million views and downloads of its 750 articles, which include English, Hebrew, and Arabic versions. The Frontiers for Young Minds editorial board currently consists of scientists and researchers from more than 64 countries.

Topics included in the journal range from astronomy and space science to biodiversity, neuroscience, pollution prevention, and mental health. Although written and edited for a younger audience, all the research published in Frontiers for Young Minds is based on solid evidence-based scientific research.

I found the Schechtman story in my December 24, 2013 posting,

I suggested earlier that this achievement has a fabulous quality and the Daniel Schechtman backstory is the reason. The winner of the 2011 Nobel Prize for Chemistry, Schechtman was reviled for years within his scientific community as Ian Sample notes in his Oct. 5, 2011 article on the announcement of Schechtman’s Nobel win written for the Guardian newspaper (Note: A link has been removed),

“A scientist whose work was so controversial he was ridiculed and asked to leave his research group has won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Daniel Shechtman, 70, a researcher at Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, received the award for discovering seemingly impossible crystal structures in frozen gobbets of metal that resembled the beautiful patterns seen in Islamic mosaics.

Images of the metals showed their atoms were arranged in a way that broke well-establised rules of how crystals formed, a finding that fundamentally altered how chemists view solid matter.

…

On the morning of 8 April 1982, Shechtman saw something quite different while gazing at electron microscope images of a rapidly cooled metal alloy. The atoms were packed in a pattern that could not be repeated. Shechtman said to himself in Hebrew, “Eyn chaya kazo,” which means “There can be no such creature.”

The bizarre structures are now known as “quasicrystals” and have been seen in a wide variety of materials. Their uneven structure means they do not have obvious cleavage planes, making them particularly hard.

…

In an interview this year with the Israeli newspaper, Haaretz, Shechtman said: “People just laughed at me.” He recalled how Linus Pauling, a colossus of science and a double Nobel laureate, mounted a frightening “crusade” against him. After telling Shechtman to go back and read a crystallography textbook, the head of his research group asked him to leave for “bringing disgrace” on the team. “I felt rejected,” Shachtman said.”

It takes a lot to persevere when most, if not all, of your colleagues are mocking and rejecting your work so bravo to Schechtman! And,bravo to the Japan-UK project researchers who have persevered to help solve at least part of a complex problem requiring that our basic notions of matter be rethought.

I encourage you to read Sample’s article in its entirety as it is well written and I’ve excerpted only bits of the story as it relates to a point I’m making in this post, i.e., perseverance in the face of extreme resistance.

Shechtman’s quasi-crystal story for Frontiers provides clear explanations and a little inspiration while not flinching away from the difficulties posed when shaking up established theories.

BTW, I like reading material written for children as there are often useful explanations that aren’t included in material intended for adults.