This device could help people with disabilities to regain control of their limbs or provide advance warnings of seizures to people with epilepsy and it’s all based on technology that is a century old.

A January 19, 2022 Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology (Skoltech) press release (also on EurekAlert) provides details about the device (Note: A link has been removed),

Scientists from Skoltech, South Ural State University, and elsewhere have developed a device for recording brain activity that is more compact and affordable than the solutions currently on the market. With its high signal quality and customizable configuration, the device could help people with restricted mobility regain control of their limbs or provide advance warnings of an impending seizure to patients with epilepsy. The article presenting the device and testing results came out in Experimental Brain Research.

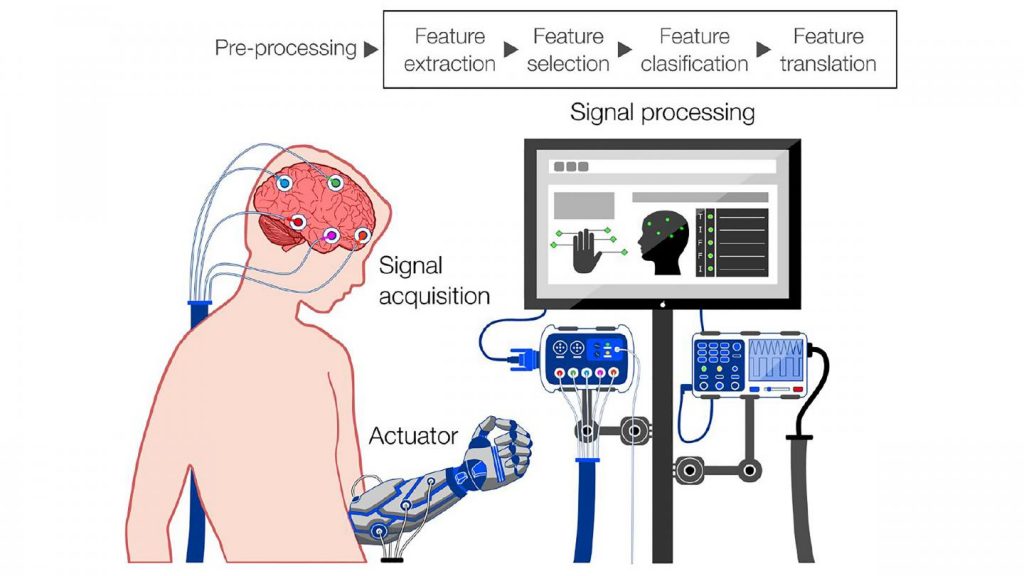

Researchers and medics, as well as engineers working on futuristic gadgets, need tools that measure brain activity. Among their scientific applications are research on sleep, decision-making, memory, and attention. In a clinical setting, these tools allow doctors to assess the extent of damage to an injured brain and monitor coma patients. Further down cyberpunk lane, brain signals can be translated into commands and sent to an external or implanted device, either to make up for lost functions in the body or for plain fun. The commands could range from moving the arm of an exoskeleton worn by a paralyzed person to turning on the TV.

Invented about a century ago, electroencephalographers are devices that read the electrical activity of the brain via small electrodes placed on the scalp. The recorded signals are then used for research, diagnostics, or gadgetry. The problem with the existing systems used in labs and hospitals is they are bulky and/or expensive. And even then, the number of electrodes is limited, resulting in moderate signal quality. Amateur devices tend to be more affordable, but with even poorer sensitivity.

To fill that gap, researchers from South Ural State University, North Carolina State University, and Brainflow — led by electronic research engineer Ildar Rakhmatulin and Skoltech neuroscientist Professor Mikhail Lebedev — created a device you can build for just $350, compared with the $1,000 or more you would need for currently available analogs. Besides being less expensive, the new electroencephalographer has as many as 24 electrodes or more. Importantly, it also provides research-grade signal quality. At half a centimeter in diameter (about 1/5 inches), the processing unit is compact enough to be worn throughout the day or during the night. The entire device weighs about 150 grams (about 5 ounces).

The researchers have made the instructions for building the device and the accompanying documentation and software openly available on GitHub. The team hopes this will attract more enthusiasts involved in brain-computer interface development, giving an impetus to support and rehabilitation system development, cognitive research, and pushing the geek community to come up with new futuristic gizmos.

“The more convenient and affordable such devices become, the more chances there are this would drive the home lab movement, with some of the research on brain-computer interfaces migrating from large science centers to small-scale amateur projects,” Lebedev said.

“Or we could see people with limited mobility using do-it-yourself interfaces to train, say, a smartphone-based system that would electrically stimulate a biceps to flex the arm at the elbow,” the researcher went on. “That works on someone who has lost control over their arm due to spinal cord trauma or a stroke, where the commands are still generated in the brain — they just don’t reach the limb, and that’s where our little brain-computer interfacing comes in.”

According to the team, such interfaces could also help patients with epilepsy by detecting tell-tale brain activity patterns that indicate when a seizure is imminent, so they can prepare by lying down comfortably in a safe space or attempting to suppress the seizure via electrical stimulation.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Low-cost brain computer interface for everyday use by Ildar Rakhmatulin, Andrey Parfenov, Zachary Traylor, Chang S. Nam & Mikhail Lebedev. Experimental Brain Research volume 239,Issue Date: December 2021, pages 3573–3583 (2021) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-021-06231-4 Published online: 29 September 2021

This paper is behind a paywall.

You can find Brainflow here and this description on its homepage: “BrainFlow is a library intended to obtain, parse and analyze EEG, EMG, ECG and other kinds of data from biosensors.”