“Feeling no pain” can be a euphemism for being drunk. However, there are some people for whom it’s not a euphemism and they literally feel no pain for one reason or another. One group of people who feel no pain are amputees and a researcher at Johns Hopkins University (Maryland, US) has found a way so they can feel pain again.

A June 20, 2018 news item on ScienceDaily provides an introduction to the research and to the reason for it,

Amputees often experience the sensation of a “phantom limb” — a feeling that a missing body part is still there.

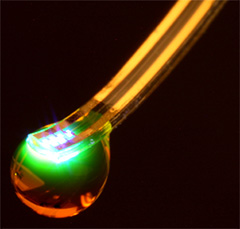

That sensory illusion is closer to becoming a reality thanks to a team of engineers at the Johns Hopkins University that has created an electronic skin. When layered on top of prosthetic hands, this e-dermis brings back a real sense of touch through the fingertips.

“After many years, I felt my hand, as if a hollow shell got filled with life again,” says the anonymous amputee who served as the team’s principal volunteer tester.

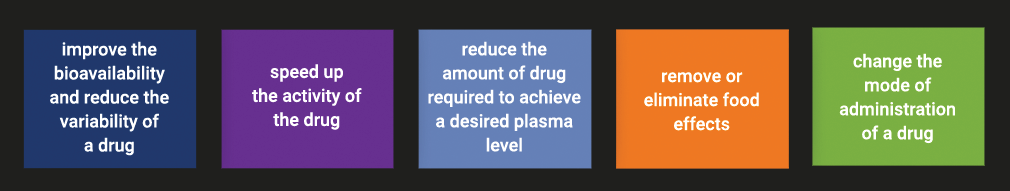

Made of fabric and rubber laced with sensors to mimic nerve endings, e-dermis recreates a sense of touch as well as pain by sensing stimuli and relaying the impulses back to the peripheral nerves.

A June 20, 2018 Johns Hopkins University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, explores the research in more depth,

“We’ve made a sensor that goes over the fingertips of a prosthetic hand and acts like your own skin would,” says Luke Osborn, a graduate student in biomedical engineering. “It’s inspired by what is happening in human biology, with receptors for both touch and pain.

“This is interesting and new,” Osborn said, “because now we can have a prosthetic hand that is already on the market and fit it with an e-dermis that can tell the wearer whether he or she is picking up something that is round or whether it has sharp points.”

The work – published June 20 in the journal Science Robotics – shows it is possible to restore a range of natural, touch-based feelings to amputees who use prosthetic limbs. The ability to detect pain could be useful, for instance, not only in prosthetic hands but also in lower limb prostheses, alerting the user to potential damage to the device.

Human skin contains a complex network of receptors that relay a variety of sensations to the brain. This network provided a biological template for the research team, which includes members from the Johns Hopkins departments of Biomedical Engineering, Electrical and Computer Engineering, and Neurology, and from the Singapore Institute of Neurotechnology.

Bringing a more human touch to modern prosthetic designs is critical, especially when it comes to incorporating the ability to feel pain, Osborn says.

“Pain is, of course, unpleasant, but it’s also an essential, protective sense of touch that is lacking in the prostheses that are currently available to amputees,” he says. “Advances in prosthesis designs and control mechanisms can aid an amputee’s ability to regain lost function, but they often lack meaningful, tactile feedback or perception.”

That is where the e-dermis comes in, conveying information to the amputee by stimulating peripheral nerves in the arm, making the so-called phantom limb come to life. The e-dermis device does this by electrically stimulating the amputee’s nerves in a non-invasive way, through the skin, says the paper’s senior author, Nitish Thakor, a professor of biomedical engineering and director of the Biomedical Instrumentation and Neuroengineering Laboratory at Johns Hopkins.

“For the first time, a prosthesis can provide a range of perceptions, from fine touch to noxious to an amputee, making it more like a human hand,” says Thakor, co-founder of Infinite Biomedical Technologies, the Baltimore-based company that provided the prosthetic hardware used in the study.

Inspired by human biology, the e-dermis enables its user to sense a continuous spectrum of tactile perceptions, from light touch to noxious or painful stimulus. The team created a “neuromorphic model” mimicking the touch and pain receptors of the human nervous system, allowing the e-dermis to electronically encode sensations just as the receptors in the skin would. Tracking brain activity via electroencephalography, or EEG, the team determined that the test subject was able to perceive these sensations in his phantom hand.

The researchers then connected the e-dermis output to the volunteer by using a noninvasive method known as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, or TENS. In a pain-detection task, the team determined that the test subject and the prosthesis were able to experience a natural, reflexive reaction to both pain while touching a pointed object and non-pain when touching a round object.

The e-dermis is not sensitive to temperature–for this study, the team focused on detecting object curvature (for touch and shape perception) and sharpness (for pain perception). The e-dermis technology could be used to make robotic systems more human, and it could also be used to expand or extend to astronaut gloves and space suits, Osborn says.

The researchers plan to further develop the technology and better understand how to provide meaningful sensory information to amputees in the hopes of making the system ready for widespread patient use.

Johns Hopkins is a pioneer in the field of upper limb dexterous prostheses. More than a decade ago, the university’s Applied Physics Laboratory led the development of the advanced Modular Prosthetic Limb, which an amputee patient controls with the muscles and nerves that once controlled his or her real arm or hand.

In addition to the funding from Space@Hopkins, which fosters space-related collaboration across the university’s divisions, the team also received grants from the Applied Physics Laboratory Graduate Fellowship Program and the Neuroengineering Training Initiative through the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering through the National Institutes of Health under grant T32EB003383.

The e-dermis was tested over the course of one year on an amputee who volunteered in the Neuroengineering Laboratory at Johns Hopkins. The subject frequently repeated the testing to demonstrate consistent sensory perceptions via the e-dermis. The team has worked with four other amputee volunteers in other experiments to provide sensory feedback.

Here’s a video about this work,

Sarah Zhang’s June 20, 2018 article for The Atlantic reveals a few more details while covering some of the material in the news release,

Osborn and his team added one more feature to make the prosthetic hand, as he puts it, “more lifelike, more self-aware”: When it grasps something too sharp, it’ll open its fingers and immediately drop it—no human control necessary. The fingers react in just 100 milliseconds, the speed of a human reflex. Existing prosthetic hands have a similar degree of theoretically helpful autonomy: If an object starts slipping, the hand will grasp more tightly. Ideally, users would have a way to override a prosthesis’s reflex, like how you can hold your hand on a stove if you really, really want to. After all, the whole point of having a hand is being able to tell it what to do.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Prosthesis with neuromorphic multilayered e-dermis perceives touch and pain by Luke E. Osborn, Andrei Dragomir, Joseph L. Betthauser, Christopher L. Hunt, Harrison H. Nguyen, Rahul R. Kaliki, and Nitish V. Thakor. Science Robotics 20 Jun 2018: Vol. 3, Issue 19, eaat3818 DOI: 10.1126/scirobotics.aat3818

This paper is behind a paywall.