In this one week, I’m publishing my first stories (see also June 13, 2023 posting “ChatGPT and a neuromorphic [brainlike] synapse“) where artificial intelligence (AI) software is combined with a memristor (hardware component) for brainlike (neuromorphic) computing.

Here’s more about some of the latest research from a March 30, 2023 news item on ScienceDaily,

Everyone is talking about the newest AI and the power of neural networks, forgetting that software is limited by the hardware on which it runs. But it is hardware, says USC [University of Southern California] Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering Joshua Yang, that has become “the bottleneck.” Now, Yang’s new research with collaborators might change that. They believe that they have developed a new type of chip with the best memory of any chip thus far for edge AI (AI in portable devices).

…

A March 29, 2023 University of Southern California (USC) news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, contextualizes the research and delves further into the topic of neuromorphic hardware,

For approximately the past 30 years, while the size of the neural networks needed for AI and data science applications doubled every 3.5 months, the hardware capability needed to process them doubled only every 3.5 years. According to Yang, hardware presents a more and more severe problem for which few have patience.

Governments, industry, and academia are trying to address this hardware challenge worldwide. Some continue to work on hardware solutions with silicon chips, while others are experimenting with new types of materials and devices. Yang’s work falls into the middle—focusing on exploiting and combining the advantages of the new materials and traditional silicon technology that could support heavy AI and data science computation.

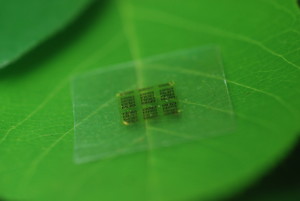

Their new paper in Nature focuses on the understanding of fundamental physics that leads to a drastic increase in memory capacity needed for AI hardware. The team led by Yang, with researchers from USC (including Han Wang’s group), MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology], and the University of Massachusetts, developed a protocol for devices to reduce “noise” and demonstrated the practicality of using this protocol in integrated chips. This demonstration was made at TetraMem, a startup company co-founded by Yang and his co-authors (Miao Hu, Qiangfei Xia, and Glenn Ge), to commercialize AI acceleration technology. According to Yang, this new memory chip has the highest information density per device (11 bits) among all types of known memory technologies thus far. Such small but powerful devices could play a critical role in bringing incredible power to the devices in our pockets. The chips are not just for memory but also for the processor. And millions of them in a small chip, working in parallel to rapidly run your AI tasks, could only require a small battery to power it.

The chips that Yang and his colleagues are creating combine silicon with metal oxide memristors in order to create powerful but low-energy intensive chips. The technique focuses on using the positions of atoms to represent information rather than the number of electrons (which is the current technique involved in computations on chips). The positions of the atoms offer a compact and stable way to store more information in an analog, instead of digital fashion. Moreover, the information can be processed where it is stored instead of being sent to one of the few dedicated ‘processors,’ eliminating the so-called ‘von Neumann bottleneck’ existing in current computing systems. In this way, says Yang, computing for AI is “more energy efficient with a higher throughput.”

How it works:

Yang explains that electrons which are manipulated in traditional chips, are “light.” And this lightness, makes them prone to moving around and being more volatile. Instead of storing memory through electrons, Yang and collaborators are storing memory in full atoms. Here is why this memory matters. Normally, says Yang, when one turns off a computer, the information memory is gone—but if you need that memory to run a new computation and your computer needs the information all over again, you have lost both time and energy. This new method, focusing on activating atoms rather than electrons, does not require battery power to maintain stored information. Similar scenarios happen in AI computations, where a stable memory capable of high information density is crucial. Yang imagines this new tech that may enable powerful AI capability in edge devices, such as Google Glasses, which he says previously suffered from a frequent recharging issue.

Further, by converting chips to rely on atoms as opposed to electrons, chips become smaller. Yang adds that with this new method, there is more computing capacity at a smaller scale. And this method, he says, could offer “many more levels of memory to help increase information density.”

To put it in context, right now, ChatGPT is running on a cloud. The new innovation, followed by some further development, could put the power of a mini version of ChatGPT in everyone’s personal device. It could make such high-powered tech more affordable and accessible for all sorts of applications.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Thousands of conductance levels in memristors integrated on CMOS by Mingyi Rao, Hao Tang, Jiangbin Wu, Wenhao Song, Max Zhang, Wenbo Yin, Ye Zhuo, Fatemeh Kiani, Benjamin Chen, Xiangqi Jiang, Hefei Liu, Hung-Yu Chen, Rivu Midya, Fan Ye, Hao Jiang, Zhongrui Wang, Mingche Wu, Miao Hu, Han Wang, Qiangfei Xia, Ning Ge, Ju Li & J. Joshua Yang. Nature volume 615, pages 823–829 (2023) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05759-5 Issue Date: 30 March 2023 Published: 29 March 2023

This paper is behind a paywall.