An August 16, 2021 news item on ScienceDaily describes a new type of neuroprosthetic,

For the more than 5 million people in the world who have undergone an upper-limb amputation, prosthetics have come a long way. Beyond traditional mannequin-like appendages, there is a growing number of commercial neuroprosthetics — highly articulated bionic limbs, engineered to sense a user’s residual muscle signals and robotically mimic their intended motions.

But this high-tech dexterity comes at a price. Neuroprosthetics can cost tens of thousands of dollars and are built around metal skeletons, with electrical motors that can be heavy and rigid.

Now engineers at MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology] and Shanghai Jiao Tong University have designed a soft, lightweight, and potentially low-cost neuroprosthetic hand. Amputees who tested the artificial limb performed daily activities, such as zipping a suitcase, pouring a carton of juice, and petting a cat, just as well as — and in some cases better than — those with more rigid neuroprosthetics.

Here’s a video demonstration,

An August 16, 2021 MIT news news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides more detail,

The researchers found the prosthetic, designed with a system for tactile feedback, restored some primitive sensation in a volunteer’s residual limb. The new design is also surprisingly durable, quickly recovering after being struck with a hammer or run over with a car.

The smart hand is soft and elastic, and weighs about half a pound. Its components total around $500 — a fraction of the weight and material cost associated with more rigid smart limbs.

“This is not a product yet, but the performance is already similar or superior to existing neuroprosthetics, which we’re excited about,” says Xuanhe Zhao, professor of mechanical engineering and of civil and environmental engineering at MIT. “There’s huge potential to make this soft prosthetic very low cost, for low-income families who have suffered from amputation.”

Zhao and his colleagues have published their work today [August 16, 2021] in Nature Biomedical Engineering. Co-authors include MIT postdoc Shaoting Lin, along with Guoying Gu, Xiangyang Zhu, and collaborators at Shanghai Jiao Tong University in China.

Big Hero hand

The team’s pliable new design bears an uncanny resemblance to a certain inflatable robot in the animated film “Big Hero 6.” Like the squishy android, the team’s artificial hand is made from soft, stretchy material — in this case, the commercial elastomer EcoFlex. The prosthetic comprises five balloon-like fingers, each embedded with segments of fiber, similar to articulated bones in actual fingers. The bendy digits are connected to a 3-D-printed “palm,” shaped like a human hand.

Rather than controlling each finger using mounted electrical motors, as most neuroprosthetics do, the researchers used a simple pneumatic system to precisely inflate fingers and bend them in specific positions. This system, including a small pump and valves, can be worn at the waist, significantly reducing the prosthetic’s weight.

Lin developed a computer model to relate a finger’s desired position to the corresponding pressure a pump would have to apply to achieve that position. Using this model, the team developed a controller that directs the pneumatic system to inflate the fingers, in positions that mimic five common grasps, including pinching two and three fingers together, making a balled-up fist, and cupping the palm.

The pneumatic system receives signals from EMG sensors — electromyography sensors that measure electrical signals generated by motor neurons to control muscles. The sensors are fitted at the prosthetic’s opening, where it attaches to a user’s limb. In this arrangement, the sensors can pick up signals from a residual limb, such as when an amputee imagines making a fist.

The team then used an existing algorithm that “decodes” muscle signals and relates them to common grasp types. They used this algorithm to program the controller for their pneumatic system. When an amputee imagines, for instance, holding a wine glass, the sensors pick up the residual muscle signals, which the controller then translates into corresponding pressures. The pump then applies those pressures to inflate each finger and produce the amputee’s intended grasp.

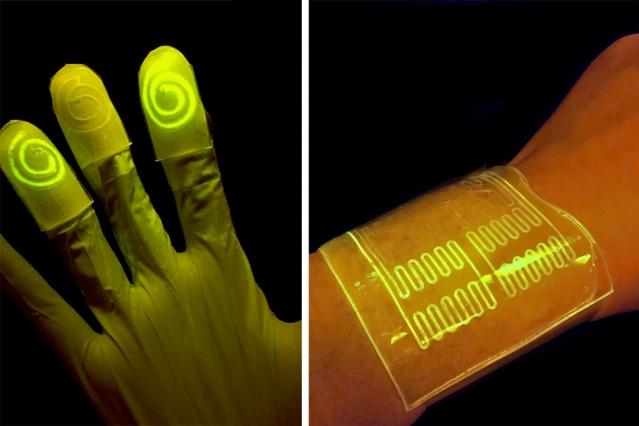

Going a step further in their design, the researchers looked to enable tactile feedback — a feature that is not incorporated in most commercial neuroprosthetics. To do this, they stitched to each fingertip a pressure sensor, which when touched or squeezed produces an electrical signal proportional to the sensed pressure. Each sensor is wired to a specific location on an amputee’s residual limb, so the user can “feel” when the prosthetic’s thumb is pressed, for example, versus the forefinger.

Good grip

To test the inflatable hand, the researchers enlisted two volunteers, each with upper-limb amputations. Once outfitted with the neuroprosthetic, the volunteers learned to use it by repeatedly contracting the muscles in their arm while imagining making five common grasps.

After completing this 15-minute training, the volunteers were asked to perform a number of standardized tests to demonstrate manual strength and dexterity. These tasks included stacking checkers, turning pages, writing with a pen, lifting heavy balls, and picking up fragile objects like strawberries and bread. They repeated the same tests using a more rigid, commercially available bionic hand and found that the inflatable prosthetic was as good, or even better, at most tasks, compared to its rigid counterpart.

One volunteer was also able to intuitively use the soft prosthetic in daily activities, for instance to eat food like crackers, cake, and apples, and to handle objects and tools, such as laptops, bottles, hammers, and pliers. This volunteer could also safely manipulate the squishy prosthetic, for instance to shake someone’s hand, touch a flower, and pet a cat.

In a particularly exciting exercise, the researchers blindfolded the volunteer and found he could discern which prosthetic finger they poked and brushed. He was also able to “feel” bottles of different sizes that were placed in the prosthetic hand, and lifted them in response. The team sees these experiments as a promising sign that amputees can regain a form of sensation and real-time control with the inflatable hand.

The team has filed a patent on the design, through MIT, and is working to improve its sensing and range of motion.

“We now have four grasp types. There can be more,” Zhao says. “This design can be improved, with better decoding technology, higher-density myoelectric arrays, and a more compact pump that could be worn on the wrist. We also want to customize the design for mass production, so we can translate soft robotic technology to benefit society.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

A soft neuroprosthetic hand providing simultaneous myoelectric control and tactile feedback by Guoying Gu, Ningbin Zhang, Haipeng Xu, Shaoting Lin, Yang Yu, Guohong Chai, Lisen Ge, Houle Yang, Qiwen Shao, Xinjun Sheng, Xiangyang Zhu, Xuanhe Zhao. Nature Biomedical Engineering (2021) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-021-00767-0 Published: 16 August 2021

This paper is behind a paywall.