Sometimes it’s hard to keep up with 3D tissue printing news. I have two news bits, one concerning eyes and another concerning brains.

3D printed human corneas

A May 29, 2018 news item on ScienceDaily trumpets the news,

The first human corneas have been 3D printed by scientists at Newcastle University, UK.

It means the technique could be used in the future to ensure an unlimited supply of corneas.

As the outermost layer of the human eye, the cornea has an important role in focusing vision.

Yet there is a significant shortage of corneas available to transplant, with 10 million people worldwide requiring surgery to prevent corneal blindness as a result of diseases such as trachoma, an infectious eye disorder.

In addition, almost 5 million people suffer total blindness due to corneal scarring caused by burns, lacerations, abrasion or disease.

The proof-of-concept research, published today [May 29, 2018] in Experimental Eye Research, reports how stem cells (human corneal stromal cells) from a healthy donor cornea were mixed together with alginate and collagen to create a solution that could be printed, a ‘bio-ink’.

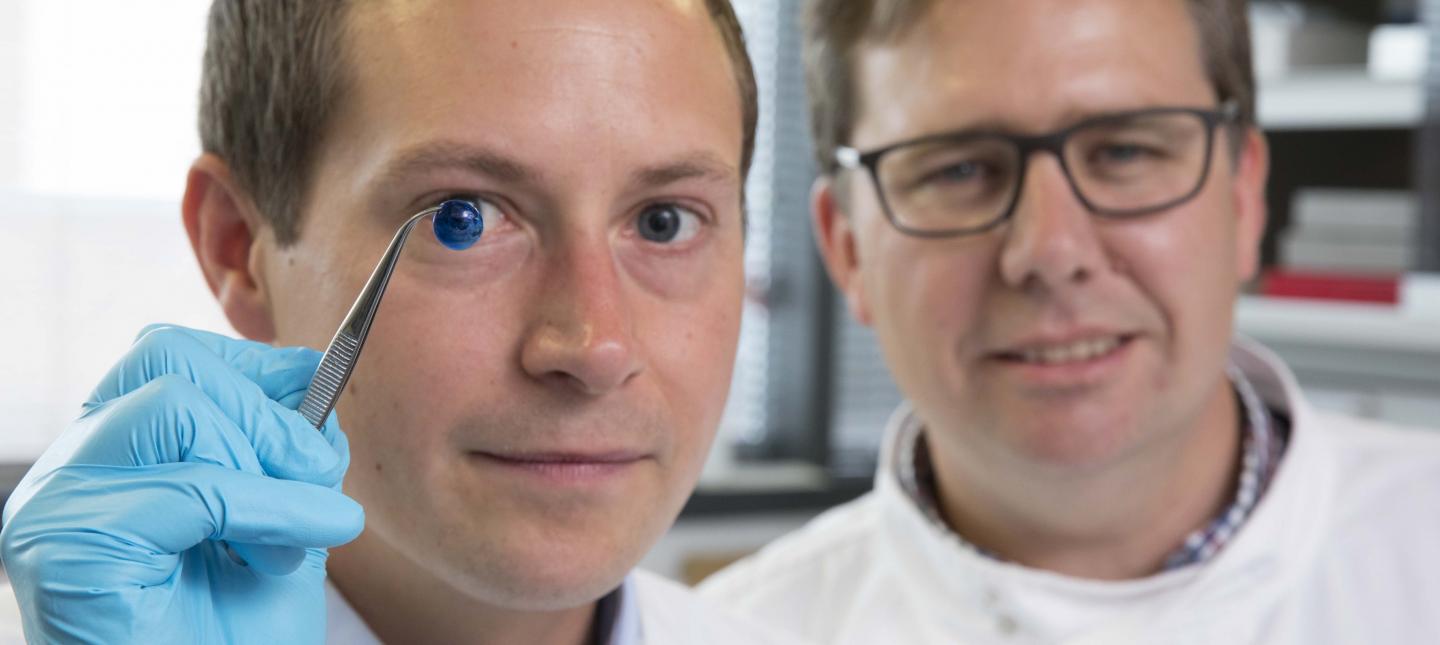

Here are the proud researchers with their cornea,

Caption: Dr. Steve Swioklo and Professor Che Connon with a dyed cornea. Credit: Newcastle University, UK

A May 30,2018 Newcastle University press release (also on EurekAlert but published on May 29, 2018), which originated the news item, adds more details,

Using a simple low-cost 3D bio-printer, the bio-ink was successfully extruded in concentric circles to form the shape of a human cornea. It took less than 10 minutes to print.

The stem cells were then shown to culture – or grow.

Che Connon, Professor of Tissue Engineering at Newcastle University, who led the work, said: “Many teams across the world have been chasing the ideal bio-ink to make this process feasible.

“Our unique gel – a combination of alginate and collagen – keeps the stem cells alive whilst producing a material which is stiff enough to hold its shape but soft enough to be squeezed out the nozzle of a 3D printer.

“This builds upon our previous work in which we kept cells alive for weeks at room temperature within a similar hydrogel. Now we have a ready to use bio-ink containing stem cells allowing users to start printing tissues without having to worry about growing the cells separately.”

The scientists, including first author and PhD student Ms Abigail Isaacson from the Institute of Genetic Medicine, Newcastle University, also demonstrated that they could build a cornea to match a patient’s unique specifications.

The dimensions of the printed tissue were originally taken from an actual cornea. By scanning a patient’s eye, they could use the data to rapidly print a cornea which matched the size and shape.

Professor Connon added: “Our 3D printed corneas will now have to undergo further testing and it will be several years before we could be in the position where we are using them for transplants.

“However, what we have shown is that it is feasible to print corneas using coordinates taken from a patient eye and that this approach has potential to combat the world-wide shortage.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

3D bioprinting of a corneal stroma equivalent by Abigail Isaacson, Stephen Swioklo, Che J. Connon. Experimental Eye Research Volume 173, August 2018, Pages 188–193 and 2018 May 14 pii: S0014-4835(18)30212-4. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2018.05.010. [Epub ahead of print]

This paper is behind a paywall.

A 3D printed copy of your brain

I love the title for this May 30, 2018 Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering news release: Creating piece of mind by Lindsay Brownell (also on EurekAlert),

What if you could hold a physical model of your own brain in your hands, accurate down to its every unique fold? That’s just a normal part of life for Steven Keating, Ph.D., who had a baseball-sized tumor removed from his brain at age 26 while he was a graduate student in the MIT Media Lab’s Mediated Matter group. Curious to see what his brain actually looked like before the tumor was removed, and with the goal of better understanding his diagnosis and treatment options, Keating collected his medical data and began 3D printing his MRI [magnetic resonance imaging] and CT [computed tomography] scans, but was frustrated that existing methods were prohibitively time-intensive, cumbersome, and failed to accurately reveal important features of interest. Keating reached out to some of his group’s collaborators, including members of the Wyss Institute at Harvard University, who were exploring a new method for 3D printing biological samples.

“It never occurred to us to use this approach for human anatomy until Steve came to us and said, ‘Guys, here’s my data, what can we do?” says Ahmed Hosny, who was a Research Fellow with at the Wyss Institute at the time and is now a machine learning engineer at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. The result of that impromptu collaboration – which grew to involve James Weaver, Ph.D., Senior Research Scientist at the Wyss Institute; Neri Oxman, [emphasis mine] Ph.D., Director of the MIT Media Lab’s Mediated Matter group and Associate Professor of Media Arts and Sciences; and a team of researchers and physicians at several other academic and medical centers in the US and Germany – is a new technique that allows images from MRI, CT, and other medical scans to be easily and quickly converted into physical models with unprecedented detail. The research is reported in 3D Printing and Additive Manufacturing.

“I nearly jumped out of my chair when I saw what this technology is able to do,” says Beth Ripley, M.D. Ph.D., an Assistant Professor of Radiology at the University of Washington and clinical radiologist at the Seattle VA, and co-author of the paper. “It creates exquisitely detailed 3D-printed medical models with a fraction of the manual labor currently required, making 3D printing more accessible to the medical field as a tool for research and diagnosis.”

Imaging technologies like MRI and CT scans produce high-resolution images as a series of “slices” that reveal the details of structures inside the human body, making them an invaluable resource for evaluating and diagnosing medical conditions. Most 3D printers build physical models in a layer-by-layer process, so feeding them layers of medical images to create a solid structure is an obvious synergy between the two technologies.

However, there is a problem: MRI and CT scans produce images with so much detail that the object(s) of interest need to be isolated from surrounding tissue and converted into surface meshes in order to be printed. This is achieved via either a very time-intensive process called “segmentation” where a radiologist manually traces the desired object on every single image slice (sometimes hundreds of images for a single sample), or an automatic “thresholding” process in which a computer program quickly converts areas that contain grayscale pixels into either solid black or solid white pixels, based on a shade of gray that is chosen to be the threshold between black and white. However, medical imaging data sets often contain objects that are irregularly shaped and lack clear, well-defined borders; as a result, auto-thresholding (or even manual segmentation) often over- or under-exaggerates the size of a feature of interest and washes out critical detail.

The new method described by the paper’s authors gives medical professionals the best of both worlds, offering a fast and highly accurate method for converting complex images into a format that can be easily 3D printed. The key lies in printing with dithered bitmaps, a digital file format in which each pixel of a grayscale image is converted into a series of black and white pixels, and the density of the black pixels is what defines the different shades of gray rather than the pixels themselves varying in color.

Similar to the way images in black-and-white newsprint use varying sizes of black ink dots to convey shading, the more black pixels that are present in a given area, the darker it appears. By simplifying all pixels from various shades of gray into a mixture of black or white pixels, dithered bitmaps allow a 3D printer to print complex medical images using two different materials that preserve all the subtle variations of the original data with much greater accuracy and speed.

The team of researchers used bitmap-based 3D printing to create models of Keating’s brain and tumor that faithfully preserved all of the gradations of detail present in the raw MRI data down to a resolution that is on par with what the human eye can distinguish from about 9-10 inches away. Using this same approach, they were also able to print a variable stiffness model of a human heart valve using different materials for the valve tissue versus the mineral plaques that had formed within the valve, resulting in a model that exhibited mechanical property gradients and provided new insights into the actual effects of the plaques on valve function.

“Our approach not only allows for high levels of detail to be preserved and printed into medical models, but it also saves a tremendous amount of time and money,” says Weaver, who is the corresponding author of the paper. “Manually segmenting a CT scan of a healthy human foot, with all its internal bone structure, bone marrow, tendons, muscles, soft tissue, and skin, for example, can take more than 30 hours, even by a trained professional – we were able to do it in less than an hour.”

The researchers hope that their method will help make 3D printing a more viable tool for routine exams and diagnoses, patient education, and understanding the human body. “Right now, it’s just too expensive for hospitals to employ a team of specialists to go in and hand-segment image data sets for 3D printing, except in extremely high-risk or high-profile cases. We’re hoping to change that,” says Hosny.

In order for that to happen, some entrenched elements of the medical field need to change as well. Most patients’ data are compressed to save space on hospital servers, so it’s often difficult to get the raw MRI or CT scan files needed for high-resolution 3D printing. Additionally, the team’s research was facilitated through a joint collaboration with leading 3D printer manufacturer Stratasys, which allowed access to their 3D printer’s intrinsic bitmap printing capabilities. New software packages also still need to be developed to better leverage these capabilities and make them more accessible to medical professionals.

Despite these hurdles, the researchers are confident that their achievements present a significant value to the medical community. “I imagine that sometime within the next 5 years, the day could come when any patient that goes into a doctor’s office for a routine or non-routine CT or MRI scan will be able to get a 3D-printed model of their patient-specific data within a few days,” says Weaver.

Keating, who has become a passionate advocate of efforts to enable patients to access their own medical data, still 3D prints his MRI scans to see how his skull is healing post-surgery and check on his brain to make sure his tumor isn’t coming back. “The ability to understand what’s happening inside of you, to actually hold it in your hands and see the effects of treatment, is incredibly empowering,” he says.

“Curiosity is one of the biggest drivers of innovation and change for the greater good, especially when it involves exploring questions across disciplines and institutions. The Wyss Institute is proud to be a space where this kind of cross-field innovation can flourish,” says Wyss Institute Founding Director Donald Ingber, M.D., Ph.D., who is also the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at Harvard Medical School (HMS) and the Vascular Biology Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, as well as Professor of Bioengineering at Harvard’s John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS).

Here’s an image illustrating the work,

Caption: This 3D-printed model of Steven Keating’s skull and brain clearly shows his brain tumor and other fine details thanks to the new data processing method pioneered by the study’s authors. Credit: Wyss Institute at Harvard University

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

From Improved Diagnostics to Presurgical Planning: High-Resolution Functionally Graded Multimaterial 3D Printing of Biomedical Tomographic Data Sets by Ahmed Hosny , Steven J. Keating, Joshua D. Dilley, Beth Ripley, Tatiana Kelil, Steve Pieper, Dominik Kolb, Christoph Bader, Anne-Marie Pobloth, Molly Griffin, Reza Nezafat, Georg Duda, Ennio A. Chiocca, James R.. Stone, James S. Michaelson, Mason N. Dean, Neri Oxman, and James C. Weaver. 3D Printing and Additive Manufacturing http://doi.org/10.1089/3dp.2017.0140 Online Ahead of Print:May 29, 2018

This paper appears to be open access.

A tangential Brad Pitt connection

It’s a bit of Hollywood gossip. There was some speculation in April 2018 that Brad Pitt was dating Dr. Neri Oxman highlighted in the Wyss Institute news release. Here’s a sample of an April 13, 2018 posting on Laineygossip (Note: A link has been removed),

It took him a long time to date, but he is now,” the insider tells PEOPLE. “He likes women who challenge him in every way, especially in the intellect department. Brad has seen how happy and different Amal has made his friend (George Clooney). It has given him something to think about.”

While a Pitt source has maintained he and Oxman are “just friends,” they’ve met up a few times since the fall and the insider notes Pitt has been flying frequently to the East Coast. He dropped by one of Oxman’s classes last fall and was spotted at MIT again a few weeks ago.

Pitt and Oxman got to know each other through an architecture project at MIT, where she works as a professor of media arts and sciences at the school’s Media Lab. Pitt has always been interested in architecture and founded the Make It Right Foundation, which builds affordable and environmentally friendly homes in New Orleans for people in need.

“One of the things Brad has said all along is that he wants to do more architecture and design work,” another source says. “He loves this, has found the furniture design and New Orleans developing work fulfilling, and knows he has a talent for it.”

It’s only been a week since Page Six first broke the news that Brad and Dr Oxman have been spending time together.

I’m fascinated by Oxman’s (and her colleagues’) furniture. Rose Brook writes about one particular Oxman piece in her March 27, 2014 posting for TCT magazine (Note: Links have been removed),

Neri Oxman in her Gemini chaise

Professor Neri Oxman reclining in her Gemini acoustic chaise featuring traditional and Stratasys additive manufacturing techniques.

2 of 3

Neri Oxman’s Gemini chaise

Chaise inner lining of Gemini Acoustic Chaise designed by Professors Neri Oxman and W. Craig Carter composed of Stratasys 3D printed PolyJet digital materials including colour with varying elastic and acoustical properties.

3 of 3

Neri Oxman’s Gemini chaise

Gemini Acoustic Chaise designed by Professors Neri Oxman and W. Craig Carter, inner lining produced on Objet500 Connex3 Colour Multi-material 3D Printer by Stratasys.

MIT Professor and 3D printing forerunner Neri Oxman has unveiled her striking acoustic chaise longue, which was made using Stratasys 3D printing technology.

Oxman collaborated with Professor W Craig Carter and Composer and fellow MIT Professor Tod Machover to explore material properties and their spatial arrangement to form the acoustic piece.

Christened Gemini, the two-part chaise was produced using a Stratasys Objet500 Connex3 multi-colour, multi-material 3D printer as well as traditional furniture-making techniques and it will be on display at the Vocal Vibrations exhibition at Le Laboratoire in Paris from March 28th 2014.

An Architect, Designer and Professor of Media, Arts and Science at MIT, Oxman’s creation aims to convey the relationship of twins in the womb through material properties and their arrangement. It was made using both subtractive and additive manufacturing and is part of Oxman’s ongoing exploration of what Stratasys’ ground-breaking multi-colour, multi-material 3D printer can do.

…

Brook goes on to explain how the chaise was made and the inspiration that led to it. Finally, it’s interesting to note that Oxman was working with Stratasys in 2014 and that this 2018 brain project is being developed in a joint collaboration with Statasys.

That’s it for 3D printing today.