Who can resist Etta James? Getting to the point of the post, I’ve been reading about nanobots for years but this is the first time I’ve seen something that resembles what lived in my imagination—at last. From a Sept. 20 , 2017 news item on phys.org (Note: Links have been removed),

Scientists at The University of Manchester have created the world’s first ‘molecular robot’ that is capable of performing basic tasks including building other molecules.

The tiny robots, which are a millionth of a millimetre in size, can be programmed to move and build molecular cargo, using a tiny robotic arm.

Each individual robot is capable of manipulating a single molecule and is made up of just 150 carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen atoms. To put that size into context, a billion billion of these robots piled on top of each other would still only be the same size as a single grain of salt.

The robots operate by carrying out chemical reactions in special solutions which can then be controlled and programmed by scientists to perform the basic tasks.

In the future such robots could be used for medical purposes, advanced manufacturing processes and even building molecular factories and assembly lines. …

A Sept. 20, 2017 University of Manchester press release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides (perhaps) a little more explanation than is absolutely necessary,

Professor David Leigh, who led the research at University’s School of Chemistry, explains: ‘All matter is made up of atoms and these are the basic building blocks that form molecules. [emphasis mine] Our robot is literally a molecular robot constructed of atoms just like you can build a very simple robot out of Lego bricks. The robot then responds to a series of simple commands that are programmed with chemical inputs by a scientist.

‘It is similar to the way robots are used on a car assembly line. Those robots pick up a panel and position it so that it can be riveted in the correct way to build the bodywork of a car. So, just like the robot in the factory, our molecular version can be programmed to position and rivet components in different ways to build different products, just on a much smaller scale at a molecular level.’

The benefit of having machinery that is so small is it massively reduces demand for materials, can accelerate and improve drug discovery, dramatically reduce power requirements and rapidly increase the miniaturisation of other products. Therefore, the potential applications for molecular robots are extremely varied and exciting.

Prof Leigh says: ‘Molecular robotics represents the ultimate in the miniaturisation of machinery. Our aim is to design and make the smallest machines possible. This is just the start but we anticipate that within 10 to 20 years molecular robots will begin to be used to build molecules and materials on assembly lines in molecular factories.’

Whilst building and operating such tiny machine is extremely complex, the techniques used by the team are based on simple chemical processes.

Prof Leigh added: ‘The robots are assembled and operated using chemistry. This is the science of how atoms and molecules react with each other and how larger molecules are constructed from smaller ones.

‘It is the same sort of process scientists use to make medicines and plastics from simple chemical building blocks. Then, once the nano-robots have been constructed, they are operated by scientists by adding chemical inputs which tell the robots what to do and when, just like a computer program.’

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Stereodivergent synthesis with a programmable molecular machine by Salma Kassem, Alan T. L. Lee, David A. Leigh, Vanesa Marcos, Leoni I. Palmer, & Simone Pisano. Nature 549,

374–378 (21 September 2017) doi:10.1038/nature23677 Published online 20 September 2017

This paper is behind a paywall.

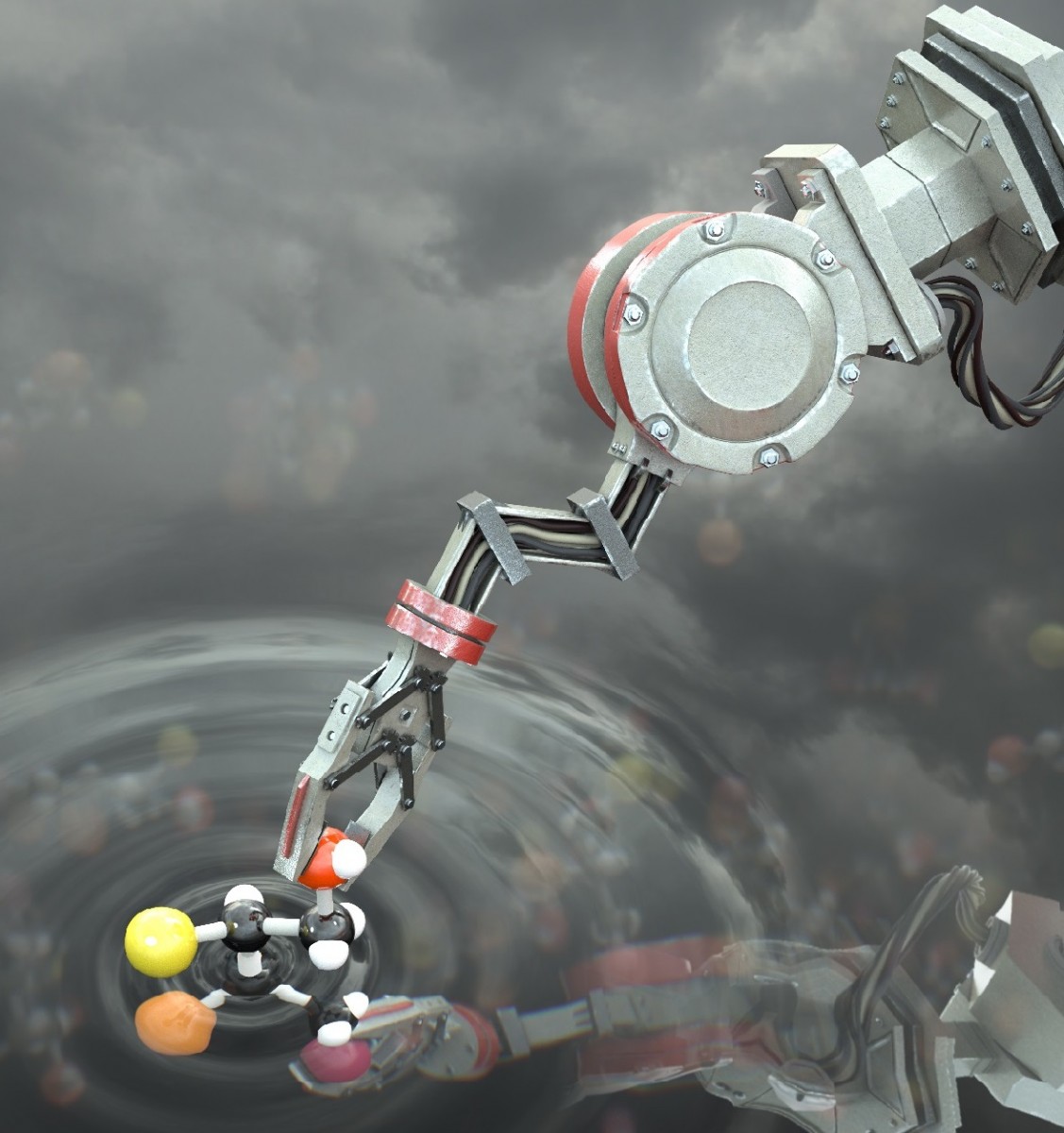

There’s a rather attractive image accompanying the news release which manages to be both quite informative and wholly unrealistic,

Courtesy: University of Manchester

Nanobots first made their way into popular science with K. Eric Drexler’s book 1986, Engines of Creation, which also provoked a spirited academic debate. See Drexler’s Wikipedia entry for more. One final comment, this would seem to be a promising start to the long-held dream of bottom-up engineering of materials.

![[downloaded from http://www.nisenet.org/blogs/observations_insights/periodic_table_nanoparticles]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/NanoparticleTableOfElements2010-300x198.png)