An hypothesis for gold’s origins was first mentioned here in a May 26, 2016 posting,

The link between this research and my side project on gold nanoparticles is a bit tenuous but this work on the origins for gold and other precious metals being found in the stars is so fascinating and I’m determined to find a connection.

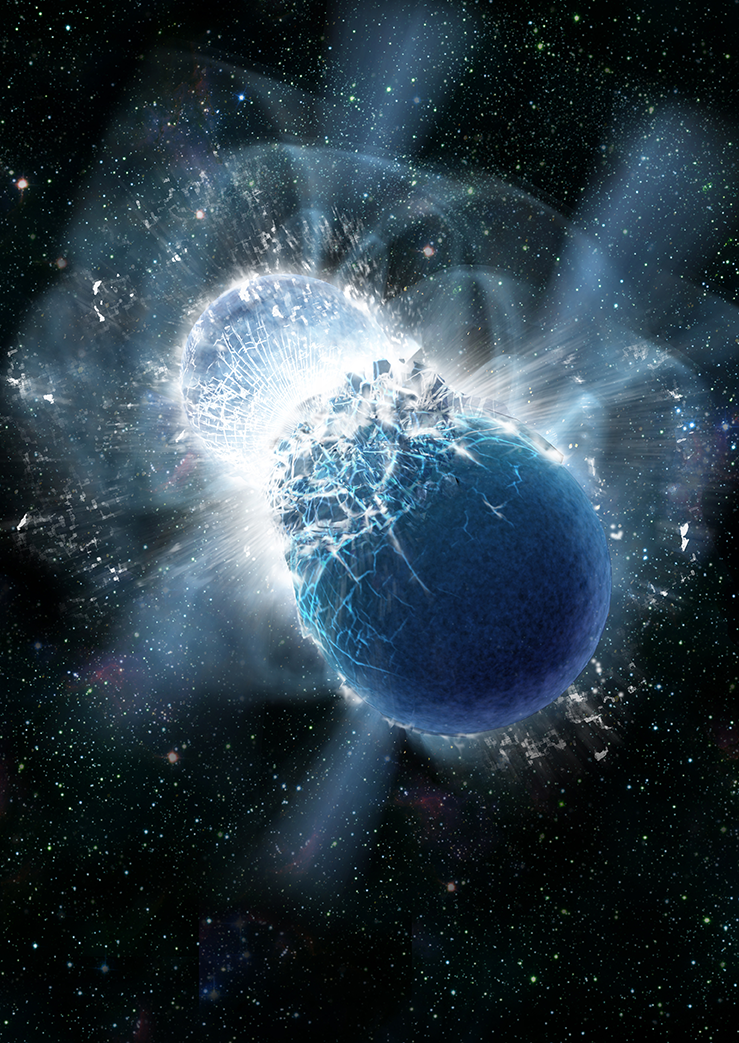

An artist’s impression of two neutron stars colliding. (Credit: Dana Berry / Skyworks Digital, Inc.) Courtesy: Kavli Foundation

From a May 19, 2016 news item on phys.org,

The origin of many of the most precious elements on the periodic table, such as gold, silver and platinum, has perplexed scientists for more than six decades. Now a recent study has an answer, evocatively conveyed in the faint starlight from a distant dwarf galaxy.

In a roundtable discussion, published today [May 19, 2016?], The Kavli Foundation spoke to two of the researchers behind the discovery about why the source of these heavy elements, collectively called “r-process” elements, has been so hard to crack.

From the Spring 2016 Kavli Foundation webpage hosting the “Galactic ‘Gold Mine’ Explains the Origin of Nature’s Heaviest Elements” Roundtable ,

…

Astronomers studying a galaxy called Reticulum II have just discovered that its stars contain whopping amounts of these metals—collectively known as “r-process” elements (See “What is the R-Process?”). Of the 10 dwarf galaxies that have been similarly studied so far, only Reticulum II bears such strong chemical signatures. The finding suggests some unusual event took place billions of years ago that created ample amounts of heavy elements and then strew them throughout the galaxy’s reservoir of gas and dust. This r-process-enriched material then went on to form Reticulum II’s standout stars.

Based on the new study, from a team of researchers at the Kavli Institute at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the unusual event in Reticulum II was likely the collision of two, ultra-dense objects called neutron stars. Scientists have hypothesized for decades that these collisions could serve as a primary source for r-process elements, yet the idea had lacked solid observational evidence. Now armed with this information, scientists can further hope to retrace the histories of galaxies based on the contents of their stars, in effect conducting “stellar archeology.”

…

Researchers have confirmed the hypothesis according to an Oct. 16, 2017 news item on phys.org,

Gold’s origin in the Universe has finally been confirmed, after a gravitational wave source was seen and heard for the first time ever by an international collaboration of researchers, with astronomers at the University of Warwick playing a leading role.

Members of Warwick’s Astronomy and Astrophysics Group, Professor Andrew Levan, Dr Joe Lyman, Dr Sam Oates and Dr Danny Steeghs, led observations which captured the light of two colliding neutron stars, shortly after being detected through gravitational waves – perhaps the most eagerly anticipated phenomenon in modern astronomy.

…

Marina Koren’s Oct. 16, 2017 article for The Atlantic presents a richly evocative view (Note: Links have been removed),

Some 130 million years ago, in another galaxy, two neutron stars spiraled closer and closer together until they smashed into each other in spectacular fashion. The violent collision produced gravitational waves, cosmic ripples powerful enough to stretch and squeeze the fabric of the universe. There was a brief flash of light a million trillion times as bright as the sun, and then a hot cloud of radioactive debris. The afterglow hung for several days, shifting from bright blue to dull red as the ejected material cooled in the emptiness of space.

Astronomers detected the aftermath of the merger on Earth on August 17. For the first time, they could see the source of universe-warping forces Albert Einstein predicted a century ago. Unlike with black-hole collisions, they had visible proof, and it looked like a bright jewel in the night sky.

But the merger of two neutron stars is more than fireworks. It’s a factory.

Using infrared telescopes, astronomers studied the spectra—the chemical composition of cosmic objects—of the collision and found that the plume ejected by the merger contained a host of newly formed heavy chemical elements, including gold, silver, platinum, and others. Scientists estimate the amount of cosmic bling totals about 10,000 Earth-masses of heavy elements.

…

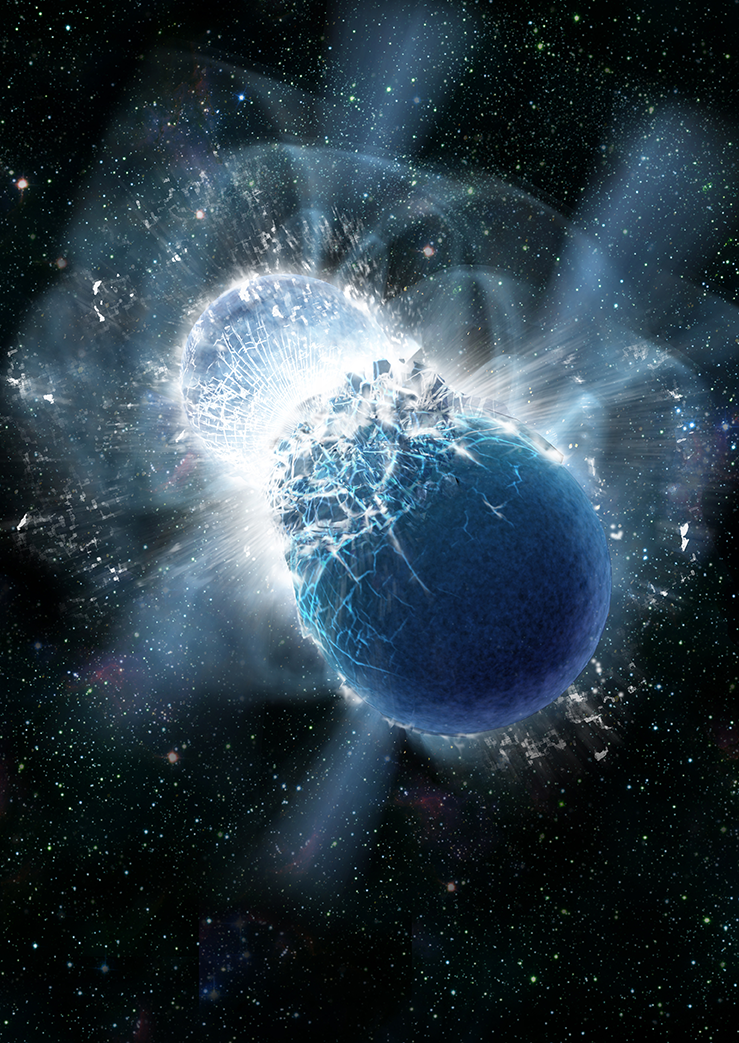

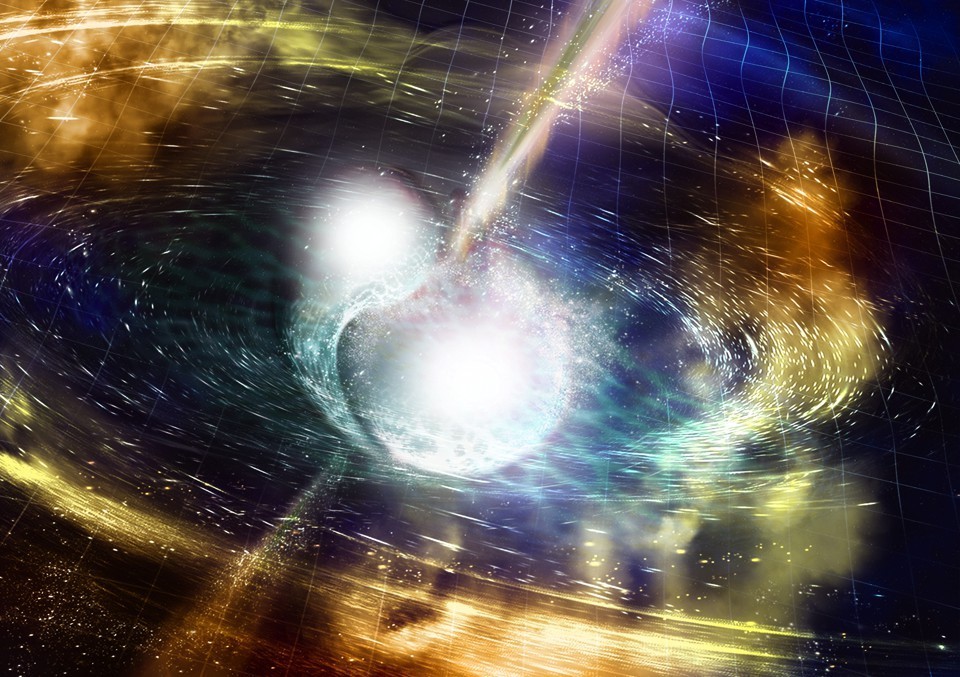

I’m not sure exactly what this image signifies but it did accompany Koren’s article so presumably it’s a representation of colliding neutron stars,

NSF / LIGO / Sonoma State University /A. Simonnet. Downloaded from: https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/10/the-making-of-cosmic-bling/543030/

An Oct. 16, 2017 University of Warwick press release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item on phys.org, provides more detail,

Huge amounts of gold, platinum, uranium and other heavy elements were created in the collision of these compact stellar remnants, and were pumped out into the universe – unlocking the mystery of how gold on wedding rings and jewellery is originally formed.

The collision produced as much gold as the mass of the Earth. [emphasis mine]

This discovery has also confirmed conclusively that short gamma-ray bursts are directly caused by the merging of two neutron stars.

The neutron stars were very dense – as heavy as our Sun yet only 10 kilometres across – and they collided with each other 130 million years ago, when dinosaurs roamed the Earth, in a relatively old galaxy that was no longer forming many stars.

They drew towards each other over millions of light years, and revolved around each other increasingly quickly as they got closer – eventually spinning around each other five hundred times per second.

Their merging sent ripples through the fabric of space and time – and these ripples are the elusive gravitational waves spotted by the astronomers.

The gravitational waves were detected by the Advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (Adv-LIGO) on 17 August this year [2017], with a short duration gamma-ray burst detected by the Fermi satellite just two seconds later.

This led to a flurry of observations as night fell in Chile, with a first report of a new source from the Swope 1m telescope.

Longstanding collaborators Professor Levan and Professor Nial Tanvir (from the University of Leicester) used the facilities of the European Southern Observatory to pinpoint the source in infrared light.

Professor Levan’s team was the first one to get observations of this new source with the Hubble Space Telescope. It comes from a galaxy called NGC 4993, 130 million light years away.

Andrew Levan, Professor in the Astronomy & Astrophysics group at the University of Warwick, commented: “Once we saw the data, we realised we had caught a new kind of astrophysical object. This ushers in the era of multi-messenger astronomy, it is like being able to see and hear for the first time.”

Dr Joe Lyman, who was observing at the European Southern Observatory at the time was the first to alert the community that the source was unlike any seen before.

He commented: “The exquisite observations obtained in a few days showed we were observing a kilonova, an object whose light is powered by extreme nuclear reactions. This tells us that the heavy elements, like the gold or platinum in jewellery are the cinders, forged in the billion degree remnants of a merging neutron star.”

Dr Samantha Oates added: “This discovery has answered three questions that astronomers have been puzzling for decades: what happens when neutron stars merge? What causes the short duration gamma-ray bursts? Where are the heavy elements, like gold, made? In the space of about a week all three of these mysteries were solved.”

Dr Danny Steeghs said: “This is a new chapter in astrophysics. We hope that in the next few years we will detect many more events like this. Indeed, in Warwick we have just finished building a telescope designed to do just this job, and we expect it to pinpoint these sources in this new era of multi-messenger astronomy”.

Congratulations to all of the researchers involved in this work!

Many, many research teams were involved. Here’s a sampling of their news releases which focus on their areas of research,

University of the Witwatersrand (South Africa)

https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2017-10/uotw-wti101717.php

Weizmann Institute of Science (Israel)

https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2017-10/wios-cns101717.php

Carnegie Institution for Science (US)

https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2017-10/cifs-dns101217.php

Northwestern University (US)

https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2017-10/nu-adc101617.php

National Radio Astronomy Observatory (US)

https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2017-10/nrao-ru101317.php

Max-Planck-Gesellschaft (Germany)

https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2017-10/m-gwf101817.php

Penn State (Pennsylvania State University; US)

https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2017-10/ps-stl101617.php

University of California – Davis

https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2017-10/uoc–cns101717.php

The American Association for the Advancement of Science’s (AAAS) magazine, Science, has published seven papers on this research. Here’s an Oct. 16, 2017 AAAS news release with an overview of the papers,

https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2017-10/aaft-btf101617.php

I’m sure there are more news releases out there and that there will be many more papers published in many journals, so if this interests, I encourage you to keep looking.

Two final pieces I’d like to draw your attention to: one answers basic questions and another focuses on how artists knew what to draw when neutron stars collide.

Keith A Spencer’s Oct. 18, 2017 piece on salon.com answers a lot of basic questions for those of us who don’t have a background in astronomy. Here are a couple of examples,

…

What is a neutron star?

Okay, you know how atoms have protons, neutrons, and electrons in them? And you know how protons are positively charged, and electrons are negatively charged, and neutrons are neutral?

Yeah, I remember that from watching Bill Nye as a kid.

Totally. Anyway, have you ever wondered why the negatively-charged electrons and the positively-charged protons don’t just merge into each other and form a neutral neutron? I mean, they’re sitting there in the atom’s nucleus pretty close to each other. Like, if you had two magnets that close, they’d stick together immediately.

I guess now that you mention it, yeah, it is weird.

Well, it’s because there’s another force deep in the atom that’s preventing them from merging.

It’s really really strong.

The only way to overcome this force is to have a huge amount of matter in a really hot, dense space — basically shove them into each other until they give up and stick together and become a neutron. This happens in very large stars that have been around for a while — the core collapses, and in the aftermath, the electrons in the star are so close to the protons, and under so much pressure, that they suddenly merge. There’s a big explosion and the outer material of the star is sloughed off.

Okay, so you’re saying under a lot of pressure and in certain conditions, some stars collapse and become big balls of neutrons?

Pretty much, yeah.

So why do the neutrons just stick around in a huge ball? Aren’t they neutral? What’s keeping them together?

Gravity, mostly. But also the strong nuclear force, that aforementioned weird strong force. This isn’t something you’d encounter on a macroscopic scale — the strong force only really works at the type of distances typified by particles in atomic nuclei. And it’s different, fundamentally, than the electromagnetic force, which is what makes magnets attract and repel and what makes your hair stick up when you rub a balloon on it.

So these neutrons in a big ball are bound by gravity, but also sticking together by virtue of the strong nuclear force.

So basically, the new ball of neutrons is really small, at least, compared to how heavy it is. That’s because the neutrons are all clumped together as if this neutron star is one giant atomic nucleus — which it kinda is. It’s like a giant atom made only of neutrons. If our sun were a neutron star, it would be less than 20 miles wide. It would also not be something you would ever want to get near.

Got it. That means two giant balls of neutrons that weighed like, more than our sun and were only ten-ish miles wide, suddenly smashed into each other, and in the aftermath created a black hole, and we are just now detecting it on Earth?

Exactly. Pretty weird, no?

…

Spencer does a good job of gradually taking you through increasingly complex explanations.

For those with artistic interests, Neel V. Patel tries to answer a question about how artists knew what draw when neutron stars collided in his Oct. 18, 2017 piece for Slate.com,

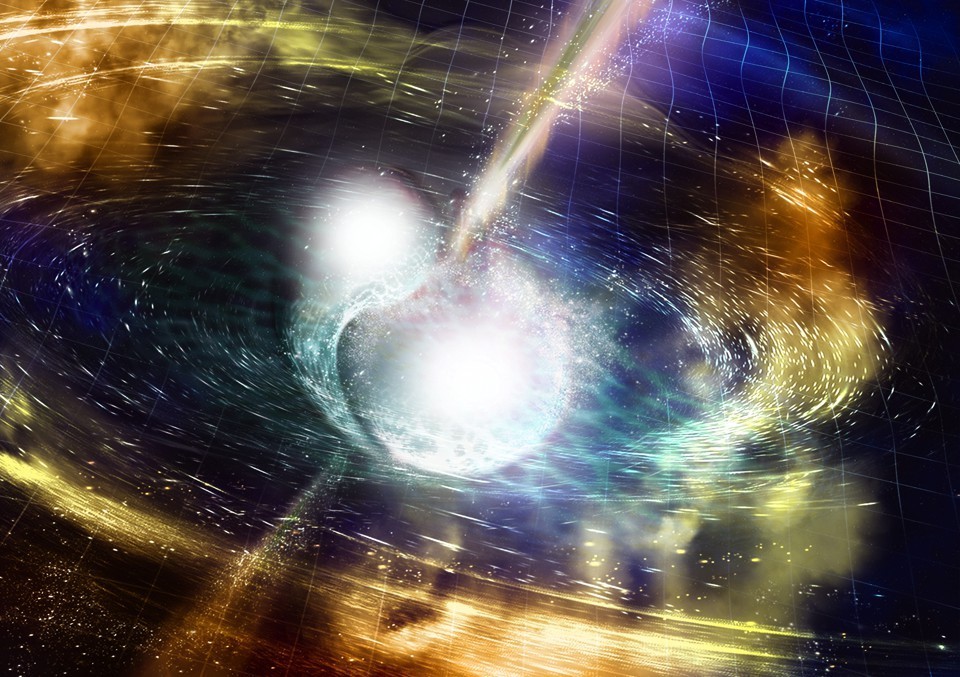

All of these things make this discovery easy to marvel at and somewhat impossible to picture. Luckily, artists have taken up the task of imagining it for us, which you’ve likely seen if you’ve already stumbled on coverage of the discovery. Two bright, furious spheres of light and gas spiraling quickly into one another, resulting in a massive swell of lit-up matter along with light and gravitational waves rippling off speedily in all directions, towards parts unknown. These illustrations aren’t just alluring interpretations of a rare phenomenon; they are, to some extent, the translation of raw data and numbers into a tangible visual that gives scientists and nonscientists alike some way of grasping what just happened. But are these visualizations realistic? Is this what it actually looked like? No one has any idea. Which is what makes the scientific illustrators’ work all the more fascinating.

“My goal is to represent what the scientists found,” says Aurore Simmonet, a scientific illustrator based at Sonoma State University in Rohnert Park, California. Even though she said she doesn’t have a rigorous science background (she certainly didn’t know what a kilonova was before being tasked to illustrate one), she also doesn’t believe that type of experience is an absolute necessity. More critical, she says, is for the artist to have an interest in the subject matter and in learning new things, as well as a capacity to speak directly to scientists about their work.

Illustrators like Simmonet usually start off work on an illustration by asking the scientist what’s the biggest takeaway a viewer should grasp when looking at a visual. Unfortunately, this latest discovery yielded a multitude of papers emphasizing different conclusions and highlights. With so many scientific angles, there’s a stark challenge in trying to cram every important thing into a single drawing.

Clearly, however, the illustrations needed to center around the kilonova. Simmonet loves colors, so she began by discussing with the researchers what kind of color scheme would work best. The smash of two neutron stars lends itself well to deep, vibrant hues. Simmonet and Robin Dienel at the Carnegie Institution for Science elected to use a wide array of colors and drew bright cracking to show pressure forming at the merging. Others, like Luis Calcada at the European Southern Observatory, limited the color scheme in favor of emphasizing the bright moment of collision and the signal waves created by the kilonova.

Animators have even more freedom to show the event, since they have much more than a single frame to play with. The Conceptual Image Lab at NASA’s [US National Aeronautics and Space Administration] Goddard Space Flight Center created a short video about the new findings, and lead animator Brian Monroe says the video he and his colleagues designed shows off the evolution of the entire process: the rising action, climax, and resolution of the kilonova event.

The illustrators try to adhere to what the likely physics of the event entailed, soliciting feedback from the scientists to make sure they’re getting it right. The swirling of gas, the direction of ejected matter upon impact, the reflection of light, the proportions of the objects—all of these things are deliberately framed such that they make scientific sense. …

Do take a look at Patel’s piece, if for no other reason than to see all of the images he has embedded there. You may recognize Aurore Simmonet’s name from the credit line in the second image I have embedded here.