This story comes from Rice University (Texas, US). From a March 12, 2018 news item on Nanowerk,

Rice University engineers have zeroed in on the optimal architecture for storing hydrogen in “white graphene” nanomaterials — a design like a Lilliputian skyscraper with “floors” of boron nitride sitting one atop another and held precisely 5.2 angstroms apart by boron nitride pillars.

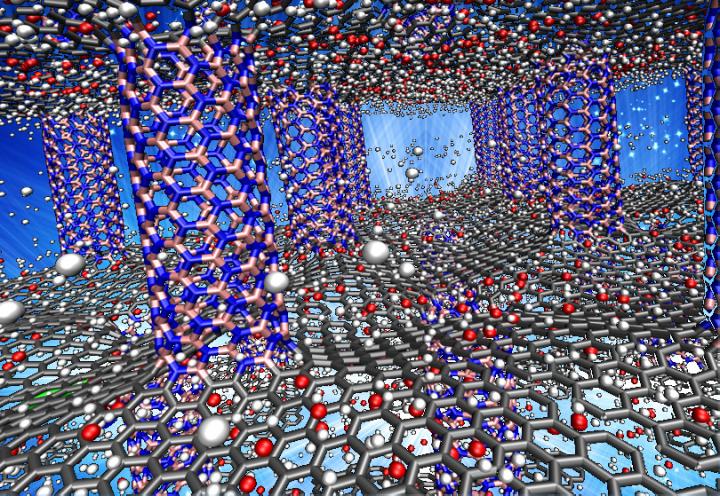

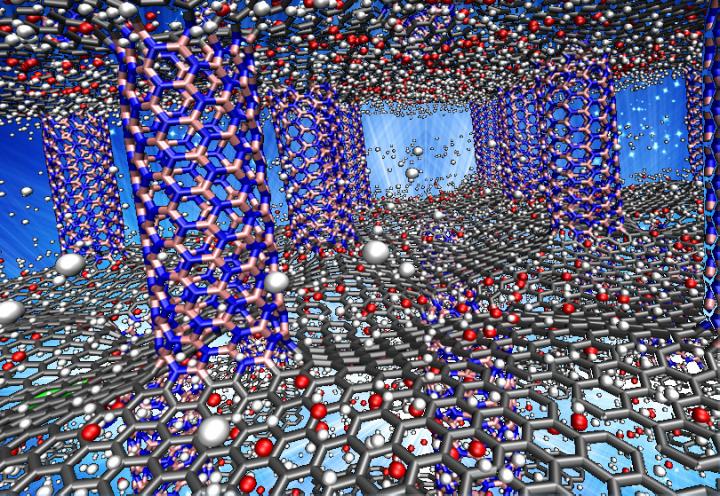

Caption Thousands of hours of calculations on Rice University’s two fastest supercomputers found that the optimal architecture for packing hydrogen into “white graphene” involves making skyscraper-like frameworks of vertical columns and one-dimensional floors that are about 5.2 angstroms apart. In this illustration, hydrogen molecules (white) sit between sheet-like floors of graphene (gray) that are supported by boron-nitride pillars (pink and blue). Researchers found that identical structures made wholly of boron-nitride had unprecedented capacity for storing readily available hydrogen. Credit Lei Tao/Rice University

A March 12, 2018 Rice University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, goes into extensive detail about the work,

“The motivation is to create an efficient material that can take up and hold a lot of hydrogen — both by volume and weight — and that can quickly and easily release that hydrogen when it’s needed,” [emphasis mine] said the study’s lead author, Rouzbeh Shahsavari, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Rice.

Hydrogen is the lightest and most abundant element in the universe, and its energy-to-mass ratio — the amount of available energy per pound of raw material, for example — far exceeds that of fossil fuels. It’s also the cleanest way to generate electricity: The only byproduct is water. A 2017 report by market analysts at BCC Research found that global demand for hydrogen storage materials and technologies will likely reach $5.4 billion annually by 2021.

Hydrogen’s primary drawbacks relate to portability, storage and safety. While large volumes can be stored under high pressure in underground salt domes and specially designed tanks, small-scale portable tanks — the equivalent of an automobile gas tank — have so far eluded engineers.

Following months of calculations on two of Rice’s fastest supercomputers, Shahsavari and Rice graduate student Shuo Zhao found the optimal architecture for storing hydrogen in boron nitride. One form of the material, hexagonal boron nitride (hBN), consists of atom-thick sheets of boron and nitrogen and is sometimes called white graphene because the atoms are spaced exactly like carbon atoms in flat sheets of graphene.

Previous work in Shahsavari’s Multiscale Materials Lab found that hybrid materials of graphene and boron nitride could hold enough hydrogen to meet the Department of Energy’s storage targets for light-duty fuel cell vehicles.

“The choice of material is important,” he said. “Boron nitride has been shown to be better in terms of hydrogen absorption than pure graphene, carbon nanotubes or hybrids of graphene and boron nitride.

“But the spacing and arrangement of hBN sheets and pillars is also critical,” he said. “So we decided to perform an exhaustive search of all the possible geometries of hBN to see which worked best. We also expanded the calculations to include various temperatures, pressures and dopants, trace elements that can be added to the boron nitride to enhance its hydrogen storage capacity.”

Zhao and Shahsavari set up numerous “ab initio” tests, computer simulations that used first principles of physics. Shahsavari said the approach was computationally intense but worth the extra effort because it offered the most precision.

“We conducted nearly 4,000 ab initio calculations to try and find that sweet spot where the material and geometry go hand in hand and really work together to optimize hydrogen storage,” he said.

Unlike materials that store hydrogen through chemical bonding, Shahsavari said boron nitride is a sorbent that holds hydrogen through physical bonds, which are weaker than chemical bonds. That’s an advantage when it comes to getting hydrogen out of storage because sorbent materials tend to discharge more easily than their chemical cousins, Shahsavari said.

He said the choice of boron nitride sheets or tubes and the corresponding spacing between them in the superstructure were the key to maximizing capacity.

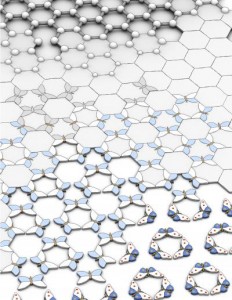

“Without pillars, the sheets sit naturally one atop the other about 3 angstroms apart, and very few hydrogen atoms can penetrate that space,” he said. “When the distance grew to 6 angstroms or more, the capacity also fell off. At 5.2 angstroms, there is a cooperative attraction from both the ceiling and floor, and the hydrogen tends to clump in the middle. Conversely, models made of purely BN tubes — not sheets — had less storage capacity.”

Shahsavari said models showed that the pure hBN tube-sheet structures could hold 8 weight percent of hydrogen. (Weight percent is a measure of concentration, similar to parts per million.) Physical experiments are needed to verify that capacity, but that the DOE’s ultimate target is 7.5 weight percent, and Shahsavari’s models suggests even more hydrogen can be stored in his structure if trace amounts of lithium are added to the hBN.

Finally, Shahsavari said, irregularities in the flat, floor-like sheets of the structure could also prove useful for engineers.

“Wrinkles form naturally in the sheets of pillared boron nitride because of the nature of the junctions between the columns and floors,” he said. “In fact, this could also be advantageous because the wrinkles can provide toughness. If the material is placed under load or impact, that buckled shape can unbuckle easily without breaking. This could add to the material’s safety, which is a big concern in hydrogen storage devices.

“Furthermore, the high thermal conductivity and flexibility of BN may provide additional opportunities to control the adsorption and release kinetics on-demand,” Shahsavari said. “For example, it may be possible to control release kinetics by applying an external voltage, heat or an electric field.”

I may be wrong but this “The motivation is to create an efficient material that can take up and hold a lot of hydrogen — both by volume and weight — and that can quickly and easily release that hydrogen when it’s needed, …” sounds like a supercapacitor. One other comment, this research appears to be ‘in silico’, i.e., all the testing has been done as computer simulations and the proposed materials themselves have yet to be tested.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Merger of Energetic Affinity and Optimal Geometry Provides New Class of Boron Nitride Based Sorbents with Unprecedented Hydrogen Storage Capacity by Rouzbeh Shahsavari and Shuo Zhao. Small Vol. 14 Issue 10 DOI: 10.1002/smll.201702863 Version of Record online: 8 MAR 2018

© 2018 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim

This paper is behind a paywall.