Unfortunately I couldn’t find a credit for the artist for the graphic (I really like it) which accompanies the news about a new physics and graphene,

From an Aug. 22, 2017 news item on phys.org (Note: A link has been removed),

A new understanding of the physics of conductive materials has been uncovered by scientists observing the unusual movement of electrons in graphene.

Graphene is many times more conductive than copper thanks, in part, to its two-dimensional structure. In most metals, conductivity is limited by crystal imperfections which cause electrons to frequently scatter like billiard balls when they move through the material.

Now, observations in experiments at the National Graphene Institute have provided essential understanding as to the peculiar behaviour of electron flows in graphene, which need to be considered in the design of future Nano-electronic circuits.

An Aug. 22, 2017 University of Manchester press release, which originated the news item, delves further into the research (Note: Links have been removed),

Appearing today in Nature Physics, researchers at The University of Manchester, in collaboration with theoretical physicists led by Professor Marco Polini and Professor Leonid Levitov, show that Landauer’s fundamental limit can be breached in graphene. Even more fascinating is the mechanism responsible for this.

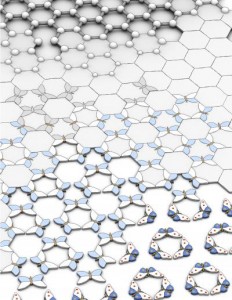

Last year, a new field in solid-state physics termed ‘electron hydrodynamics’ generated huge scientific interest. Three different experiments, including one performed by The University of Manchester, demonstrated that at certain temperatures, electrons collide with each other so frequently they start to flow collectively like a viscous fluid.

The new research demonstrates that this viscous fluid is even more conductive than ballistic electrons. The result is rather counter-intuitive, since typically scattering events act to lower the conductivity of a material, because they inhibit movement within the crystal. However, when electrons collide with each other, they start working together and ease current flow.

This happens because some electrons remain near the crystal edges, where momentum dissipation is highest, and move rather slowly. At the same time, they protect neighbouring electrons from colliding with those regions. Consequently, some electrons become super-ballistic as they are guided through the channel by their friends.

Sir Andre Geim said: “We know from school that additional disorder always creates extra electrical resistance. In our case, disorder induced by electron scattering actually reduces rather than increase resistance. This is unique and quite counterintuitive: Electrons when make up a liquid start propagating faster than if they were free, like in vacuum”.

The researchers measured the resistance of graphene constrictions, and found it decreases upon increasing temperature, in contrast to the usual metallic behaviour expected for doped graphene.

By studying how the resistance across the constrictions changes with temperature, the scientists revealed a new physical quantity which they called the viscous conductance. The measurements allowed them to determine electron viscosity to such a high precision that the extracted values showed remarkable quantitative agreement with theory.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Superballistic flow of viscous electron fluid through graphene constrictions by R. Krishna Kumar, D. A. Bandurin, F. M. D. Pellegrino, Y. Cao, A. Principi, H. Guo, G. H. Auton, M. Ben Shalom, L. A. Ponomarenko, G. Falkovich, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, I. V. Grigorieva, L. S. Levitov, M. Polini, & A. K. Geim. Nature Physics (2017) doi:10.1038/nphys4240 Published online 21 August 2017

This paper is behind a paywall.