Yes, it’s a ‘Top Gun’ movie quote (1986) or more accurately, a paraphrasing of Tom Cruise’s line “I feel the need for speed.” I understand there’s a sequel, which is due to arrive in movie theatres or elsewhere at sometime in this decade.

Where wireless and WiFi are concerned I think there is a dog/poodle situation. ‘Dog’ is a general description where ‘poodle’ is a specific description. All poodles (specific) are dogs (general) but not all dogs are poodles. So, wireless is a general description and Wi-Fi is a specific type of wireless communication. All WiFi is wireless but not all wireless is Wi-Fi. That said, onto the research.

Given what seems to be an insatiable desire for speed in the wireless world, the quote seems quite à propos in relation to the latest work on quantum tunneling and its impact on Wi-Fi speed from the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (from a February 3, 2021 news item on phys.org,

Scientists from MIPT (Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology), Moscow Pedagogical State University and the University of Manchester have created a highly sensitive terahertz detector based on the effect of quantum-mechanical tunneling in graphene. The sensitivity of the device is already superior to commercially available analogs based on semiconductors and superconductors, which opens up prospects for applications of the graphene detector in wireless communications, security systems, radio astronomy, and medical diagnostics. The research results are published in Nature Communications.

A February 3, 2021 MIPT press release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides more technical detail about the work and its relation WiFi,

Information transfer in wireless networks is based on transformation of a high-frequency continuous electromagnetic wave into a discrete sequence of bits. This technique is known as signal modulation. To transfer the bits faster, one has to increase the modulation frequency. However, this requires synchronous increase in carrier frequency. A common FM-radio transmits at frequencies of hundred megahertz, a Wi-Fi receiver uses signals of roughly five gigahertz frequency, while the 5G mobile networks can transmit up to 20 gigahertz signals. This is far from the limit, and further increase in carrier frequency admits a proportional increase in data transfer rates. Unfortunately, picking up signals with hundred gigahertz frequencies and higher is an increasingly challenging problem.

A typical receiver used in wireless communications consists of a transistor-based amplifier of weak signals and a demodulator that rectifies the sequence of bits from the modulated signal. This scheme originated in the age of radio and television, and becomes inefficient at frequencies of hundreds of gigahertz desirable for mobile systems. The fact is that most of the existing transistors aren’t fast enough to recharge at such a high frequency.

An evolutionary way to solve this problem is just to increase the maximum operation frequency of a transistor. Most specialists in the area of nanoelectronics work hard in this direction. A revolutionary way to solve the problem was theoretically proposed in the beginning of 1990’s by physicists Michael Dyakonov and Michael Shur, and realized, among others, by the group of authors in 2018. It implies abandoning active amplification by transistor, and abandoning a separate demodulator. What’s left in the circuit is a single transistor, but its role is now different. It transforms a modulated signal into bit sequence or voice signal by itself, due to non-linear relation between its current and voltage drop.

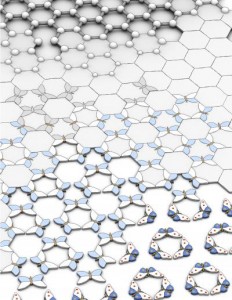

In the present work, the authors have proved that the detection of a terahertz signal is very efficient in the so-called tunneling field-effect transistor. To understand its work, one can just recall the principle of an electromechanical relay, where the passage of current through control contacts leads to a mechanical connection between two conductors and, hence, to the emergence of current. In a tunneling transistor, applying voltage to the control contact (termed as ”gate”) leads to alignment of the energy levels of the source and channel. This also leads to the flow of current. A distinctive feature of a tunneling transistor is its very strong sensitivity to control voltage. Even a small “detuning” of energy levels is enough to interrupt the subtle process of quantum mechanical tunneling. Similarly, a small voltage at the control gate is able to “connect” the levels and initiate the tunneling current

“The idea of ??a strong reaction of a tunneling transistor to low voltages is known for about fifteen years,” says Dr. Dmitry Svintsov, one of the authors of the study, head of the laboratory for optoelectronics of two-dimensional materials at the MIPT center for photonics and 2D materials. “But it’s been known only in the community of low-power electronics. No one realized before us that the same property of a tunneling transistor can be applied in the technology of terahertz detectors. Georgy Alymov (co-author of the study) and I were lucky to work in both areas. We realized then: if the transistor is opened and closed at a low power of the control signal, then it should also be good in picking up weak signals from the ambient surrounding. “

The created device is based on bilayer graphene, a unique material in which the position of energy levels (more strictly, the band structure) can be controlled using an electric voltage. This allowed the authors to switch between classical transport and quantum tunneling transport within a single device, with just a change in the polarities of the voltage at the control contacts. This possibility is of extreme importance for an accurate comparison of the detecting ability of a classical and quantum tunneling transistor.

The experiment showed that the sensitivity of the device in the tunnelling mode is few orders of magnitude higher than that in the classical transport mode. The minimum signal distinguishable by the detector against the noisy background already competes with that of commercially available superconducting and semiconductor bolometers. However, this is not the limit – the sensitivity of the detector can be further increased in “cleaner” devices with a low concentration of residual impurities. The developed detection theory, tested by the experiment, shows that the sensitivity of the “optimal” detector can be a hundred times higher.

“The current characteristics give rise to great hopes for the creation of fast and sensitive detectors for wireless communications,” says the author of the work, Dr. Denis Bandurin. And this area is not limited to graphene and is not limited to tunnel transistors. We expect that, with the same success, a remarkable detector can be created, for example, based on an electrically controlled phase transition. Graphene turned out to be just a good launching pad here, just a door, behind which is a whole world of exciting new research.”

The results presented in this paper are an example of a successful collaboration between several research groups. The authors note that it is this format of work that allows them to obtain world-class scientific results. For example, earlier, the same team of scientists demonstrated how waves in the electron sea of ??graphene can contribute to the development of terahertz technology. “In an era of rapidly evolving technology, it is becoming increasingly difficult to achieve competitive results.” – comments Dr. Georgy Fedorov, deputy head of the nanocarbon materials laboratory, MIPT, – “Only by combining the efforts and expertise of several groups can we successfully realize the most difficult tasks and achieve the most ambitious goals, which we will continue to do.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the latest paper,

Tunnel field-effect transistors for sensitive terahertz detection by I. Gayduchenko, S. G. Xu, G. Alymov, M. Moskotin, I. Tretyakov, T. Taniguchi, K. Watanabe, G. Goltsman, A. K. Geim, G. Fedorov, D. Svintsov & D. A. Bandurin. Nature Communications volume 12, Article number: 543 (2021) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20721-z Published: 22 January 2021

This paper is open access.

One last comment, I’m assuming since the University of Manchester is mentioned that A. K. Geim is Sir Andre K. Geim (you can look him up here is you’re not familiar with his role in the graphene research community).