An October 22, 2023 commentary by Rae Hodge for Salon.com introduces the new work with a beautiful lede/lead and more,

A recently published scientific article proposes a sweeping new law of nature, approaching the matter with dry, clinical efficiency that still reads like poetry.

“A pervasive wonder of the natural world is the evolution of varied systems, including stars, minerals, atmospheres, and life,” the scientists write in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. “Evolving systems are asymmetrical with respect to time; they display temporal increases in diversity, distribution, and/or patterned behavior,” they continue, mounting their case from the shoulders of Charles Darwin, extending it toward all things living and not.

To join the known physics laws of thermodynamics, electromagnetism and Newton’s laws of motion and gravity, the nine scientists and philosophers behind the paper propose their “law of increasing functional information.”

In short, a complex and evolving system — whether that’s a flock of gold finches or a nebula or the English language — will produce ever more diverse and intricately detailed states and configurations of itself.

And here, any writer should find their breath caught in their throat. Any writer would have to pause and marvel.

It’s a rare thing to hear the voice of science singing toward its twin in the humanities. The scientists seem to be searching in their paper for the right words to describe the way the nested trills of a flautist rise through a vaulted cathedral to coalesce into notes themselves not played by human breath. And how, in the very same way, the oil-slick sheen of a June Bug wing may reveal its unseen spectra only against the brief-blooming dogwood in just the right season of sun.

Both intricate configurations of art and matter arise and fade according to their shared characteristic, long-known by students of the humanities: each have been graced with enough time to attend to the necessary affairs of their most enduring pleasures.

…

If you have the time, do read this October 22, 2023 commentary as Hodge waxes eloquent.

An October 16, 2023 news item on phys.org announces the work in a more prosaic fashion,

A paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences describes “a missing law of nature,” recognizing for the first time an important norm within the natural world’s workings.

In essence, the new law states that complex natural systems evolve to states of greater patterning, diversity, and complexity. In other words, evolution is not limited to life on Earth, it also occurs in other massively complex systems, from planets and stars to atoms, minerals, and more.

It was authored by a nine-member team— scientists from the Carnegie Institution for Science, the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and Cornell University, and philosophers from the University of Colorado.

…

An October 16, 2023 Carnegie Science Earth and Planets Laboratory news release on EurekAlert (there is also a somewhat shorter October 16, 2023 version on the Carnegie Science [Carnegie Institution of Science] website), which originated the news item, provides a lot more detail,

“Macroscopic” laws of nature describe and explain phenomena experienced daily in the natural world. Natural laws related to forces and motion, gravity, electromagnetism, and energy, for example, were described more than 150 years ago.

The new work presents a modern addition — a macroscopic law recognizing evolution as a common feature of the natural world’s complex systems, which are characterised as follows:

- They are formed from many different components, such as atoms, molecules, or cells, that can be arranged and rearranged repeatedly

- Are subject to natural processes that cause countless different arrangements to be formed

- Only a small fraction of all these configurations survive in a process called “selection for function.”

Regardless of whether the system is living or nonliving, when a novel configuration works well and function improves, evolution occurs.

The authors’ “Law of Increasing Functional Information” states that the system will evolve “if many different configurations of the system undergo selection for one or more functions.”

“An important component of this proposed natural law is the idea of ‘selection for function,’” says Carnegie astrobiologist Dr. Michael L. Wong, first author of the study.

In the case of biology, Darwin equated function primarily with survival—the ability to live long enough to produce fertile offspring.

The new study expands that perspective, noting that at least three kinds of function occur in nature.

The most basic function is stability – stable arrangements of atoms or molecules are selected to continue. Also chosen to persist are dynamic systems with ongoing supplies of energy.

The third and most interesting function is “novelty”—the tendency of evolving systems to explore new configurations that sometimes lead to startling new behaviors or characteristics.

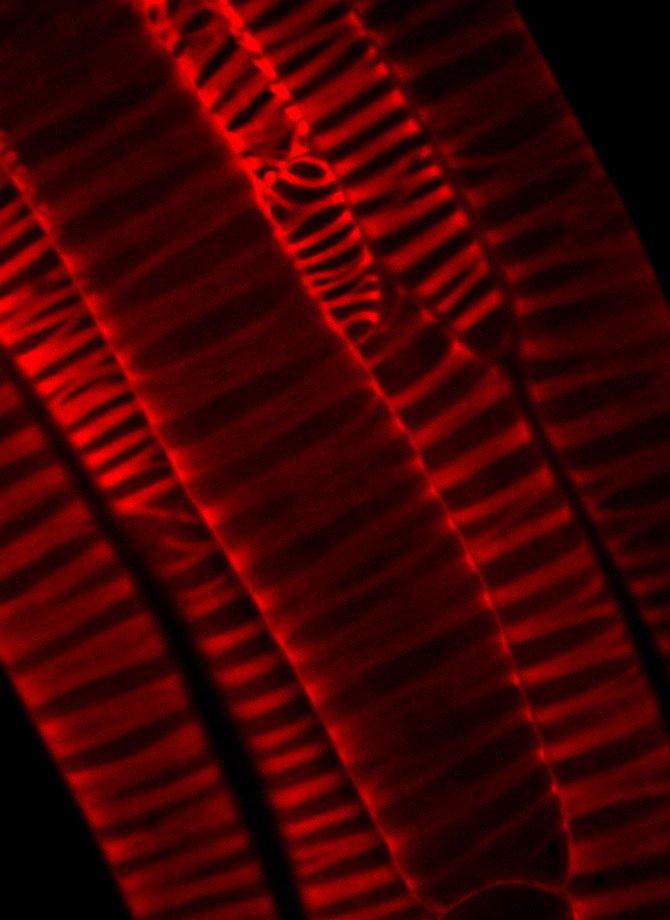

Life’s evolutionary history is rich with novelties—photosynthesis evolved when single cells learned to harness light energy, multicellular life evolved when cells learned to cooperate, and species evolved thanks to advantageous new behaviors such as swimming, walking, flying, and thinking.

The same sort of evolution happens in the mineral kingdom. The earliest minerals represent particularly stable arrangements of atoms. Those primordial minerals provided foundations for the next generations of minerals, which participated in life’s origins. The evolution of life and minerals are intertwined, as life uses minerals for shells, teeth, and bones.

Indeed, Earth’s minerals, which began with about 20 at the dawn of our Solar System, now number almost 6,000 known today thanks to ever more complex physical, chemical, and ultimately biological processes over 4.5 billion years.

In the case of stars, the paper notes that just two major elements – hydrogen and helium – formed the first stars shortly after the big bang. Those earliest stars used hydrogen and helium to make about 20 heavier chemical elements. And the next generation of stars built on that diversity to produce almost 100 more elements.

“Charles Darwin eloquently articulated the way plants and animals evolve by natural selection, with many variations and traits of individuals and many different configurations,” says co-author Robert M. Hazen of Carnegie Science, a leader of the research.

“We contend that Darwinian theory is just a very special, very important case within a far larger natural phenomenon. The notion that selection for function drives evolution applies equally to stars, atoms, minerals, and many other conceptually equivalent situations where many configurations are subjected to selective pressure.”

The co-authors themselves represent a unique multi-disciplinary configuration: three philosophers of science, two astrobiologists, a data scientist, a mineralogist, and a theoretical physicist.

Says Dr. Wong: “In this new paper, we consider evolution in the broadest sense—change over time—which subsumes Darwinian evolution based upon the particulars of ‘descent with modification.’”

“The universe generates novel combinations of atoms, molecules, cells, etc. Those combinations that are stable and can go on to engender even more novelty will continue to evolve. This is what makes life the most striking example of evolution, but evolution is everywhere.”

Among many implications, the paper offers:

- Understanding into how differing systems possess varying degrees to which they can continue to evolve. “Potential complexity” or “future complexity” have been proposed as metrics of how much more complex an evolving system might become

- Insights into how the rate of evolution of some systems can be influenced artificially. The notion of functional information suggests that the rate of evolution in a system might be increased in at least three ways: (1) by increasing the number and/or diversity of interacting agents, (2) by increasing the number of different configurations of the system; and/or 3) by enhancing the selective pressure on the system (for example, in chemical systems by more frequent cycles of heating/cooling or wetting/drying).

- A deeper understanding of generative forces behind the creation and existence of complex phenomena in the universe, and the role of information in describing them

- An understanding of life in the context of other complex evolving systems. Life shares certain conceptual equivalencies with other complex evolving systems, but the authors point to a future research direction, asking if there is something distinct about how life processes information on functionality (see also https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsif.2022.0810).

- Aiding the search for life elsewhere: if there is a demarcation between life and non-life that has to do with selection for function, can we identify the “rules of life” that allow us to discriminate that biotic dividing line in astrobiological investigations? (See also https://conta.cc/3LwLRYS, “Did Life Exist on Mars? Other Planets? With AI’s Help, We May Know Soon”)

- At a time when evolving AI systems are an increasing concern, a predictive law of information that characterizes how both natural and symbolic systems evolve is especially welcome

Laws of nature – motion, gravity, electromagnetism, thermodynamics – etc. codify the general behavior of various macroscopic natural systems across space and time.

The “law of increasing functional information” published today complements the 2nd law of thermodynamics, which states that the entropy (disorder) of an isolated system increases over time (and heat always flows from hotter to colder objects).

* * * * *

Comments

“This is a superb, bold, broad, and transformational article. … The authors are approaching the fundamental issue of the increase in complexity of the evolving universe. The purpose is a search for a ‘missing law’ that is consistent with the known laws.

“At this stage of the development of these ideas, rather like the early concepts in the mid-19th century of coming to understand ‘energy’ and ‘entropy,’ open broad discussion is now essential.”

Stuart Kauffman

Institute for Systems Biology, Seattle WA“The study of Wong et al. is like a breeze of fresh air blowing over the difficult terrain at the trijunction of astrobiology, systems science and evolutionary theory. It follows in the steps of giants such as Erwin Schrödinger, Ilya Prigogine, Freeman Dyson and James Lovelock. In particular, it was Schrödinger who formulated the perennial puzzle: how can complexity increase — and drastically so! — in living systems, while they remain bound by the Second Law of thermodynamics? In the pile of attempts to resolve this conundrum in the course of the last 80 years, Wong et al. offer perhaps the best shot so far.”

“Their central idea, the formulation of the law of increasing functional information, is simple but subtle: a system will manifest an increase in functional information if its various configurations generated in time are selected for one or more functions. This, the authors claim, is the controversial ‘missing law’ of complexity, and they provide a bunch of excellent examples. From my admittedly quite subjective point of view, the most interesting ones pertain to life in radically different habitats like Titan or to evolutionary trajectories characterized by multiple exaptations of traits resulting in a dramatic increase in complexity. Does the correct answer to Schrödinger’s question lie in this direction? Only time will tell, but both my head and my gut are curiously positive on that one. Finally, another great merit of this study is worth pointing out: in this day and age of rabid Counter-Enlightenment on the loose, as well as relentless attacks on the freedom of thought and speech, we certainly need more unabashedly multidisciplinary and multicultural projects like this one.”

Milan Cirkovic

Astronomical Observatory of Belgrade, Serbia; The Future of Humanity Institute, Oxford University [University of Oxford]The natural laws we recognize today cannot yet account for one astounding characteristic of our universe—the propensity of natural systems to “evolve.” As the authors of this study attest, the tendency to increase in complexity and function through time is not specific to biology, but is a fundamental property observed throughout the universe. Wong and colleagues have distilled a set of principles which provide a foundation for cross-disciplinary discourse on evolving systems. In so doing, their work will facilitate the study of self-organization and emergent complexity in the natural world.

Corday Selden

Department of Marine and Coastal Sciences, Rutgers UniversityThe paper “On the roles of function and selection in evolving systems” provides an innovative, compelling, and sound theoretical framework for the evolution of complex systems, encompassing both living and non-living systems. Pivotal in this new law is functional information, which quantitatively captures the possibilities a system has to perform a function. As some functions are indeed crucial for the survival of a living organism, this theory addresses the core of evolution and is open to quantitative assessment. I believe this contribution has also the merit of speaking to different scientific communities that might find a common ground for open and fruitful discussions on complexity and evolution.

Andrea Roli

Assistant Professor, Università di Bologna.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

On the roles of function and selection in evolving systems by Michael L. Wong, Carol E. Cleland, Daniel Arends Jr., Stuart Bartlett, H. James Cleaves, Heather Demarest, Anirudh Prabhu, Jonathan I. Lunine, and Robert M. Hazen. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) 120 (43) e2310223120 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2310223120 Published: October 16, 2023

This paper is open access.