I have not seen aluminum called aluminium in quite some time. (I’ve always had a fondness for that extra syllable.) I first saw notice of this work from Austria in an October 11, 2021 news item on Nanowerk,

A novel electronic component from TU Wien (Vienna) could be an important key to the era of quantum information technology: Using a special manufacturing process, pure germanium is bonded with aluminium in a way that atomically sharp interfaces are created. This results in a so-called monolithic metal-semiconductor-metal heterostructure.

This structure shows unique effects that are particularly evident at low temperatures. The aluminium becomes superconducting – but not only that, this property is also transferred to the adjacent germanium semiconductor and can be specifically controlled with electric fields. This makes it excellently suited for complex applications in quantum technology, such as processing quantum bits.

A particular advantage is that using this approach, it is not necessary to develop completely new technologies. Instead, mature and well established semiconductor fabrication techniqueses can be used to enable germanium-based quantum electronics.

An October 6, 2021 Technical University of Vienna (TU Wien) press release (also on EurekAlert but published October 12, 2021), which originated the news item, delves into the technical details and the importance of temperature,

Germanium: difficult to form high-quality contacts

“Germanium is a material which will definitely play an important role in semiconductor technology for the development of faster and more energy-efficient components,” says Dr. Masiar Sistani from the Institute for Solid State Electronics at TU Wien. However, if it is used to produce components on a nanometre scale, major problems arise: the material makes it extremely difficult to produce high-quality electrical contacts. This is related to the high impact of even smallest impurities at the contact points that significantly alter the electrical properties. “We have therefore set ourselves the task of developing a new manufacturing method that enables reliable and reproducible contact properties”, says Masiar Sistani.

Diffusing atoms

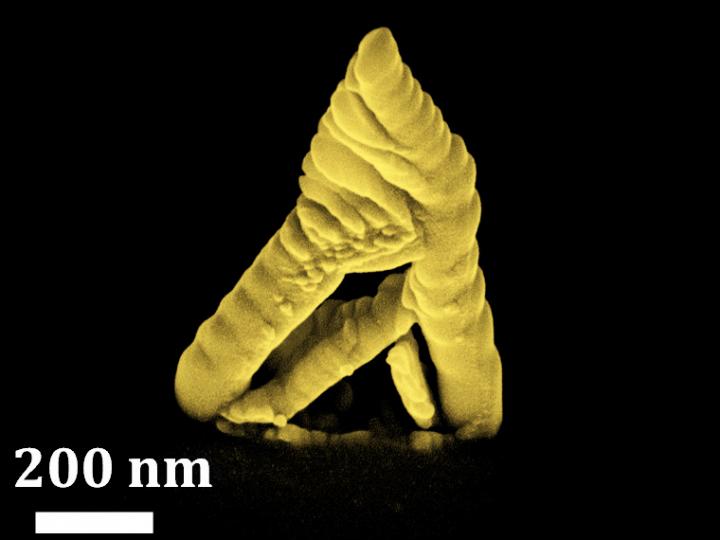

The key is temperature: when nanometre-structured germanium and aluminium are brought into contact and heated, the atoms of both materials begin to diffuse into the neighbouring material – but to very different extents: the germanium atoms move rapidly into the aluminium, whereas aluminium hardly diffuses into the germanium at all. “Thus, if you connect two aluminium contacts to a thin germanium nanowire and raise the temperature to 350 degrees Celsius, the germanium atoms diffuse off the edge of the nanowire. This creates empty spaces into which the aluminium can then easily penetrate,” explains Masiar Sistani. “In the end, only a few nanometre area in the middle of the nanowire consists of germanium, the rest has been filled up by aluminium.”

Normally, aluminium is made up of tiny crystal grains, but this novel fabrication method forms a perfect single crystal in which the aluminium atoms are arranged in a uniform pattern. As can be seen under the transmission electron microscope, a perfectly clean and atomically sharp transition is formed between germanium and aluminium, with no disordered region in between. In contrast to conventional methods where electrical contacts are applied to a semiconductor, for example by evaporating a metal, no oxides can form at the boundary layer.

Quantum transport in Grenoble

In order to take a closer look at the properties of this monolithic metal-semiconductor heterostructure of germanium and aluminium at low temperature, we collaborated with Dr. Olivier Buisson and Dr. Cécile Naud from the quantum electronics circuits group at Néel Institute – CNRS-UGA [Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique; Université Grenoble Alpes] in Grenoble. It turned out that the novel structure indeed has quite remarkable properties: “Not only were we able to demonstrate superconductivity in pure, undoped germanium for the first time, we were also able to show that this structure can be switched between quite different operating states using electric fields. Such a germanium quantum dot device can not only be superconducting but also completely insulating, or it can behave like a Josephson transistor, an important basic element of quantum electronic circuits,” explains Masiar Sistani.

This new heterostructure combines a whole range of advantages: The structure has excellent physical properties needed for quantum technologies, such as high carrier mobility and excellent manipulability with electric fields, and it has the additional advantage of fitting well with already established microelectronics technologies: Germanium is already used in current chip architectures and the temperatures required for heterostructure formation are compatible with well-established semiconductor processing schemes. The novel structures not only have theoretically interesting quantum properties, but also opens up a technologically very realistic possibility of enabling further novel and energy-saving devices.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Al–Ge–Al Nanowire Heterostructure: From Single-Hole Quantum Dot to Josephson Effect by Jovian Delaforce, Masiar Sistani, Roman B. G. Kramer, Minh A. Luong, Nicolas Roch, Walter M. Weber, Martien I. den Hertog, Eric Robin, Cecile Naud, Alois Lugstein, Olivier Buisson. Advanced Materials Volume 33, Issue 39 October 1, 2021 2101989 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202101989 First published [online]: 08 August 2021

This paper is behind a paywall.