I have two news items concerning ribonucleic acid interference (RNAi). The first item features Tekmira Pharmaceuticals Corporation (a Canadian company located in the Vancouver area) and a licencing deal with Dicerna Pharmaceuticals (Massachusetts, US), according to a Nov. 18, 2014 news item on Azonano,

Tekmira Pharmaceuticals Corporation a leading developer of RNA interference (RNAi) therapeutics, today announces a licensing and collaboration agreement with Dicerna Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Tekmira has licensed its proprietary lipid nanoparticle (LNP) delivery technology for exclusive use in Dicerna’s primary hyperoxaluria type 1 (PH1) development program.

Under the agreement, Dicerna will pay Tekmira $2.5 million upfront and payments of $22 million in aggregate development milestones, plus a mid-single-digit royalty on future PH1 sales. This new partnership also includes a supply agreement with Tekmira providing clinical drug supply and regulatory support in the rapid advancement of the product candidate.

The agreement announced today follows the successful testing and demonstration of positive results combining Tekmira’s LNP technology with DCR-PH1 in pre-clinical animal models.

I don’t entirely understand what they mean by “pre-clinical animal models” as I’ve not noticed the term “pre-clinical” applied to animal testing before this. It’s possible they mean they’ve run tests on animals (in vivo) and are now proceeding to human clinical trials or it could mean they’ve run in silico (computer modeling) or in vitro (test tube/test slide) tests and are now proceeding to animal tests. If anyone should have some insights, please do share them with me in the comments section.

A Nov. 17, 2014 Tekmira news release, which originated the news item, describes the deal in more detail,

Dicerna will use Tekmira’s third generation LNP technology for delivery of DCR-PH1, Dicerna’s Dicer substrate RNA (DsiRNA) molecule, for the treatment of PH1, a rare, inherited liver disorder that often results in kidney failure and for which there are no approved therapies.

“This new agreement validates our leadership position in RNAi delivery with LNP technology, and it underscores the significant value we can bring to partners who leverage our technology. Our LNP technology is enabling the most advanced applications of RNAi therapeutics in the clinic, and it continues to do so. We are excited to be working with Dicerna to be able to advance a needed therapeutic for the treatment of PH1,” said Dr. Mark J. Murray, Tekmira’s President and CEO.

“As a core pillar of our business strategy, we continue to engage in partnerships where our technology improves the risk profile and accelerates the development programs of our collaborators and provides meaningful non-dilutive financing to TKMR,” added Dr. Murray.

“Dicerna is focused on realizing the full clinical potential of our proprietary pipeline of highly targeted RNAi therapies by applying proven technologies,” said Douglas Fambrough, Ph.D., Chief Executive Officer of Dicerna. “By drawing on Tekmira’s extensive and deep experience with lipid nanoparticle delivery to the liver, the agreement will streamline the development path for DCR-PH1. We look forward to initiating Phase 1 trials of DCR-PH1 in 2015, aiming to fill a high unmet medical need for patients with PH1.”

The news release also provides a high level description of the various technologies being researched and brought to market and a bit more information about the liver disorder being addressed by this research,

About RNAi

RNAi therapeutics have the potential to treat a number of human diseases by “silencing” disease-causing genes. The discoverers of RNAi, a gene silencing mechanism used by all cells, were awarded the 2006 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. RNAi trigger molecules often require delivery technology to be effective as therapeutics.

AboutTekmira’s LNP Technology

Tekmira believes its LNP technology represents the most widely adopted delivery technology for the systemic delivery of RNAi triggers. Tekmira’s LNP platform is being utilized in multiple clinical trials by Tekmira and its partners. Tekmira’s LNP technology (formerly referred to as stable nucleic acid-lipid particles, or SNALP) encapsulates RNAi triggers with high efficiency in uniform lipid nanoparticles that are effective in delivering these therapeutic compounds to disease sites. Tekmira’s LNP formulations are manufactured by a proprietary method which is robust, scalable and highly reproducible, and LNP-based products have been reviewed by multiple regulatory agencies for use in clinical trials. LNP formulations comprise several lipid components that can be adjusted to suit the specific application.

About Primary Hyperoxaluria Type 1 ( PH1)

PH1 is a rare, inherited liver disorder that often results in severe damage to the kidneys. The disease can be fatal unless the patient undergoes a liver-kidney transplant, a major surgical procedure that is often difficult to perform due to the lack of donors and the threat of organ rejection. In the event of a successful transplant, the patient must live the rest of his or her life on immunosuppressant drugs, which have substantial associated risks. Currently, there are no FDA approved treatments for PH1.

PH1 is characterized by a genetic deficiency of the liver enzyme alanine:glyoxalate-aminotransferase (AGT), which is encoded by the AGXT gene. AGT deficiency induces overproduction of oxalate by the liver, resulting in the formation of crystals of calcium oxalate in the kidneys. Oxalate crystal formation often leads to chronic and painful cases of kidney stones and subsequent fibrosis (scarring), which is known as nephrocalcinosis. Many patients progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and require dialysis or transplant. Aside from having to endure frequent dialysis, PH1 patients with ESRD may experience a build-up of oxalate in the bone, skin, heart and retina, with concomitant debilitating complications. While the true prevalence of primary hyperoxaluria is unknown, it is estimated to be one to three cases per one million people.1 Fifty percent of patients with PH1 reach ESRD by their mid-30s.2

About DCR-PH1

Dicerna is developing DCR-PH1, which is in preclinical development, for the treatment of PH1. DCR-PH1 is engineered to address the pathology of PH1 by targeting and destroying the messenger RNA (mRNA) produced by HAO1, a gene implicated in the pathogenesis of PH1. HAO1 encodes glycolate oxidase, a protein involved in producing oxalate. By reducing oxalate production, this approach is designed to prevent the complications of PH1. In preclinical studies, DCR-PH1 has been shown to induce potent and long-term inhibition of HAO1 and to significantly reduce levels of urinary oxalate, while demonstrating long-term efficacy and tolerability in animal models of PH1.

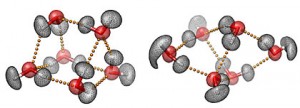

About Dicerna’s Dicer Substrate Technology

Dicerna’s proprietary RNAi molecules are known as Dicer substrates, or DsiRNAs, so called because they are processed by the Dicer enzyme, which is the initiation point for RNAi in the human cell cytoplasm. Dicerna’s discovery approach is believed to maximize RNAi potency because the DsiRNAs are structured to be ideal for processing by Dicer. Dicer processing enables the preferential use of the correct RNA strand of the DsiRNA, which may increase the efficacy of the RNAi mechanism, as well as the potency of the DsiRNA molecules relative to other molecules used to induce RNAi.

You can find more information about Tekmira here and about Dicerna here. I mentioned Tekmira previously in a Sept. 28, 2014 post about Ebola and treatments.

Further south at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD), researcher and founder of Solstice Biologics, Dr Steven Dowdy has developed and patented a new technique for delivering RNAi drugs into cells according to a Nov. 18, 2014 news item on Azonano,

Small pieces of synthetic RNA trigger a RNA interference (RNAi) response that holds great therapeutic potential to treat a number of diseases, especially cancer and pandemic viruses. The problem is delivery — it is extremely difficult to get RNAi drugs inside the cells in which they are needed. To overcome this hurdle, researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have developed a way to chemically disguise RNAi drugs so that they are able to enter cells. Once inside, cellular machinery converts these disguised drug precursors — called siRNNs — into active RNAi drugs. …

A Nov. 17, 2014 UCSD news release (also on EurekAlert) by Heather Buschman, which originated the news item, describes the issues with delivering RNAi drugs to cells and the new technique,

“Many current approaches use nanoparticles to deliver RNAi drugs into cells,” said Steven F. Dowdy, PhD, professor in the Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine and the study’s principal investigator. “While nanotechnology protects the RNAi drug, from a molecular perspective nanoparticles are huge, some 5,000 times larger than the RNAi drug itself. Think of delivering a package into your house by having an 18-wheeler truck drive it through your living room wall — that’s nanoparticles carrying standard RNAi drugs. Now think of a package being slipped through the mail slot — that’s siRNNs.”

The beauty of RNAi is that it selectively blocks production of target proteins in a cell, a finding that garnered a Nobel Prize in 2006. While this is a normal process that all cells use, researchers have taken advantage of RNAi to inhibit specific proteins that cause disease when overproduced or mutated, such as in cancer. First, researchers generate RNAi drugs with a sequence that corresponds to the gene blueprint for the disease protein and then delivers them into cells. Once inside the cell, the RNAi drug is loaded into an enzyme that specifically slices the messenger RNA encoding the target protein in half. This way, no protein is produced.

As cancer and viral genes mutate, RNAi drugs can be easily evolved to target them. This allows RNAi therapy to keep pace with the genetics of the disease — something that no other type of therapy can do. Unfortunately, due to their size and negatively charged chemical groups (phosphates) on their backbone, RNAi drugs are repelled by the cellular membrane and cannot be delivered into cells without a special delivery agent.

It took Dowdy and his team, including Bryan Meade, PhD, Khirud Gogoi, PhD, and Alexander S. Hamil, eight years to find a way to mask RNAi’s negative phosphates in such a way that gets them into cells, but is still capable of inducing an RNAi response once inside.

In the end, the team added a chemical tag called a phosphotriester group. The phosphotriester neutralizes and protects the RNA backbone — converting the ribonucleic acid (RNA) to ribonucleic neutral (RNN), and thus giving the name siRNN. The neutral (uncharged) nature of siRNNs allows them to pass into the cell much more efficiently. Once inside the cell, enzymes cleave off the neutral phosphotriester group to expose a charged RNAi drug that shuts down production of the target disease protein. siRNNs represent a transformational next-generation RNAi drug.

“siRNNs are precursor drugs, or prodrugs, with no activity. It’s like having a tool still in the box, it won’t work until you take it out,” Dowdy said. “Only when the packaging — the phosphotriester groups — is removed inside the cells do you have an active tool or RNAi drug.”

The findings held up in a mouse model, too. There, Dowdy’s team found that siRNNs were significantly more effective at blocking target protein production than typical RNAi drugs — demonstrating that once siRNNs get inside a cell they can do a better job.

“There remains a lot of work ahead to get this into the clinics. But, in theory, the therapeutic potential of siRNNs is endless,” Dowdy said. “Particularly for cancer, viral infections and genetic diseases.”

The siRNN technology forms the basis for Solstice Biologics, a biotech company in La Jolla, Calif. that is now taking the technique to the next level. Dowdy is a co-founder of Solstice Biologics and serves as a Board Director.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the research paper,

Efficient delivery of RNAi prodrugs containing reversible charge-neutralizing phosphotriester backbone modifications by Bryan R Meade, Khirud Gogoi, Alexander S Hamil, Caroline Palm-Apergi, Arjen van den Berg, Jonathan C Hagopian, Aaron D Springer, Akiko Eguchi, Apollo D Kacsinta, Connor F Dowdy, Asaf Presente, Peter Lönn, Manuel Kaulich, Naohisa Yoshioka, Edwige Gros, Xian-Shu Cui, & Steven F Dowdy. Nature Biotechnology (2014) doi:10.1038/nbt.3078 Published online 17 November 2014

This paper is behind a paywall.

I have not been able to locate a website for Solstice Biologics but did find a rather curious item about Dr. Dowdy and a shooting incident last year. From a Sept. 18, 2013 news article by Kat Robinson for thewire.sheknows.com,

A wealthy San Diego community is shaken after a man opens fire on his former neighborhood early Wednesday morning. Police say Hans Petersen, a 48-year-old man, is the prime suspect in the shooting of Steven Dowdy and Michael Fletcher.

There’s also a Nov. 8, 2013 article about the incident by Lucas Laursen for Nature magazine,

On September 18 [2013], former Traversa Therapeutics CEO Hans Petersen went on a shooting spree. One of two people wounded was molecular biologist Steven Dowdy, a professor at University of California San Diego (UCSD) School of Medicine, in La Jolla, and cofounder of Traversa, according to a San Diego police report.…

The rest of the article is behind a paywall.