Georgina Lohan

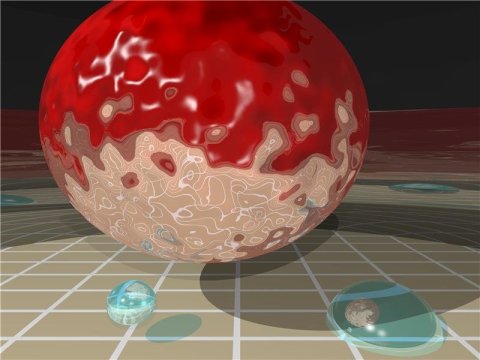

Vancouver (Canada) artist Georgina Lohan’s latest show was a departure of sorts. Better known for her tableware and jewelry, her art exhibit showcased ceramic sculptures ranging in height from 16 inches to over seven feet and incorporating concepts from biology, species evolution, mythology, philosophy, sociology, and archaeology to convey imagery associated with the primordial world.

Perhaps one of the most striking elements of Lohan’s work is its beauty. This is not a quality one often sees in contemporary art. If she were fish, Lohan could be seen as swimming against the tide.

Origins II 62″ x 24″ Porcelain, steel 2016 Courtesy: Georgina Lohan

Within a context that encompasses beauty and the primordial ooze, she is representing many of the disturbing themes seen in contemporary art: fragmentation, loss, destruction, and, indirectly, war.

The artist deliberately exploits the structural fragility of her pieces (four of them had to be anchored to the walls of the gallery). From Lohan’s own writings about the show,

The repetitive nature of loss and destruction when working with a fragile medium has consolidated my tactic of collage porcelain debris as well as a consideration of the fragment as signifier for a larger totality.

…

The heat of the kiln is equivalent to an acceleration of time. Gravity becomes a critical force at these high temperatures and strategies of support become more and more necessary the larger and heavier the pieces become. Glazes liquefy, boil and bubble before smoothing out, colour change, the work expands and shrinks, moving and changing it molecular structure, growing crystals and other phenomena. The results can unpredictable and there is a high level of risk, but there are also those alchemical moments when base metals have turned to gold.

Sadly, the show ended Aug. 11, 2016 but Lohan has plans for future shows. You can find out more at her website.

Bharti Kher

The Vancouver Art Gallery (VAG) is showcasing UK-born, New Delhi-based artist Bharti Kher in North America’s first 20 year retrospective of her work, titled ‘Matter’, from July 9, 2016 to Oct. 10, 2016.

I saw the show on a Tuesday (Aug. 16, 2016) which features entry by donation from 5 pm. Depending on how you feel about crowds, you may want to get there early for the lineup. (The Picasso show which is also happening is quite the attraction, more about Picasso: The Artist and His Muses later in this post.

There is a lot to this show so I’m concentrating on elements of special interest to me: the goddess sculptures, the ‘fabric pieces’, and one of the bindi pieces.

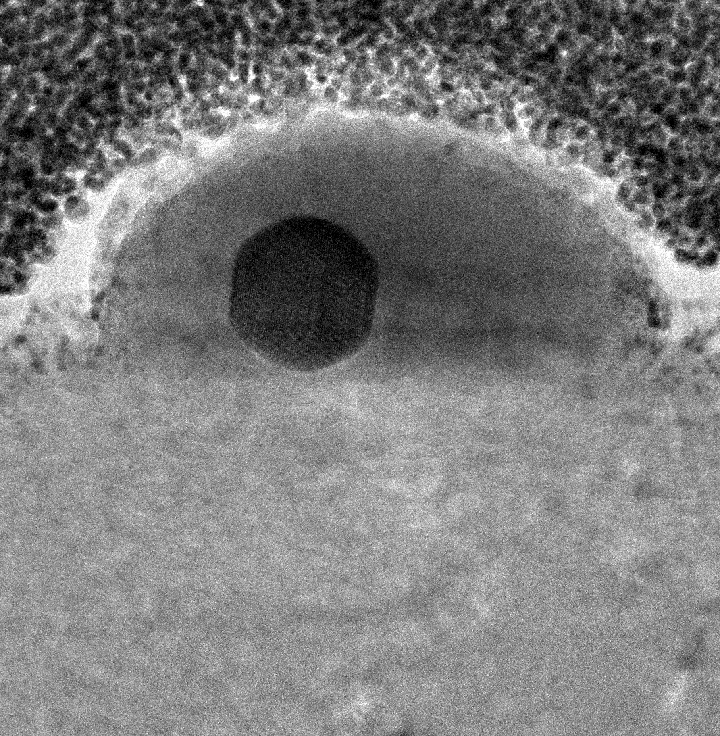

The sculptures of the women incorporating animal pelts, fragile teacups, and/or antlers fascinated me. I was particularly intrigued by ‘And all the while the benevolent slept’ (2008).

Bharti Kher’s And all the while the benevolent slept, 2008. Credit: Guillaume Ziccarelli

Here’s what Kher is doing with this goddess according to a June 28, 2016 VAG news release,

Through her use of a particular body type or character, Kher’s sculptures make reference to iconic figures from mythology and history. And all the while the benevolent slept (2008) references Chinnamasta, an Indian goddess Kali who, in traditional iconography, holds her own detached head in her hand, blood gushing from her neck, while she stands on top of a copulating couple. Through her self-sacrifice she awakens the awareness of spiritual energy while at the same time incarnating sexual energy

Kher’s ‘Chinnamasta’ stands on a tree stump and has branches growing out of her neck rather than pouring blood. For someone from a province where forestry is a major industry, this piece lends itself to a political/ecological reading, as well as, as a reading of the feminine which is so much a part of Kher’s work. The skull does not seem wholly human.

The artist does not explain the piece beyond noting its origins in traditional Indian iconography. Here’s more about Chinnamasta from its Wikipedia entry (Note: Links have been removed),

Chhinnamasta (Sanskrit: छिन्नमस्ता, Chinnamastā, “She whose head is severed”), often spelled Chinnamasta, and also called Chhinnamastika and Prachanda Chandika, is one of the Mahavidyas, ten Tantric goddesses and a ferocious aspect of Devi, the Hindu Divine Mother. Chhinnamasta can be easily identified by her unusual iconography. The nude self-decapitated goddess, usually standing or seated on a copulating couple, holds her own severed head in one hand, a scimitar in another. Three jets of blood spurt out of her bleeding neck and are drunk by her severed head and two attendants.

Chhinnamasta is a goddess of contradictions. She symbolises both aspects of Devi: a life-giver and a life-taker. She is considered both a symbol of sexual self-control and an embodiment of sexual energy, depending upon interpretation. She represents death, temporality, and destruction as well as life, immortality, and recreation. The goddess conveys spiritual self-realization and the awakening of the kundalini – spiritual energy. The legends of Chhinnamasta emphasise her self-sacrifice – sometimes coupled with a maternal element – sexual dominance, and self-destructive fury.

In reading more about Chinnamasta, the piece grows in intrigue.

Moving on to the ‘fabric pieces, there’s this from the June 28, 2016 VAG news release,

Bharti Kher’s furniture and sari sculptures speaks to socially constructed ideals of femininity and domesticity. Any utilitarian function has been rendered useless, and instead these pieces of furniture become proxies for a body. The sari-draped chairs in Absence (2011) introduces the possibility of domestic narratives filled with mothers, daughters, wives and lovers, whose bodiless garments preserve a former presence. In The day they met (2011), vibrant and richly patterned saris are decisively placed on a staircase, effectively embalming the ritual act of sari unwrapping.

Bharti Kher, Absence, 2011, sari, resin, wooden chair. Private Collection Courtesy of the Artist and Galerie Peerotin, Photo Guillaume Ziccarelli

The saris appear on various pieces of furniture and sometimes appear as twisted, long rolls that could be said to resemble snakes. The fabrics are beautiful and they call to mind Lohan’s work and also ‘women’s work’.

Now for the bindis. For anyone not familiar with bindis, there’s this from its Wikipedia entry (Note: Links have been removed),

A bindi (Hindi: बिंदी, from Sanskrit bindu, meaning “point, drop, dot or small particle”) is a red dot worn on the center of the forehead, commonly by Hindu and Jain women. The word Bindu dates back to the hymn of creation known as Nasadiya Sukta in Rig Veda.[1] Bindu is considered the point at which creation begins and may become unity. It is also described as “the sacred symbol of the cosmos in its unmanifested state”.[2][3] Bindi is a bright dot of red colour applied in the center of the forehead close to the eyebrow worn in Indian Subcontinent (particularly amongst Hindus in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka)[2] and Southeast Asia among Bali and Javanese Hindus. Bindi in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism is associated with Ajna Chakra and Bindu[4] is known as the third eye chakra. Bindu is the point or dot around which the mandala is created, representing the universe.[3][5] Bindi has historical and cultural presence in the region of Greater India.[6][7]

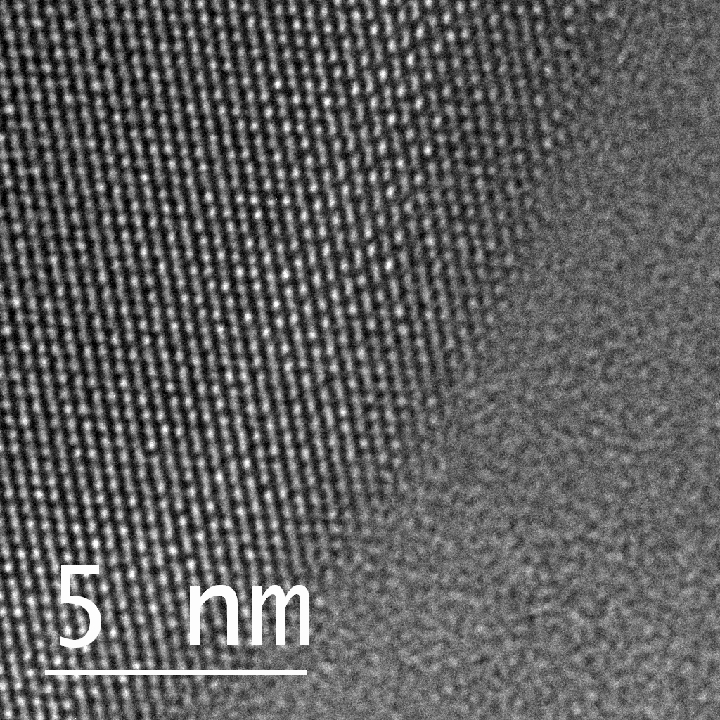

The first piece you see in the Matter show is Virus VII (2016). It is comprised of bindis, blues ones rather than the traditional red, painstakingly overlapped in a spiral that extends several feet in height and width and affixed to the wall. The piece is accompanied by a wooden box with a plaque and containing sheets of blue bindis,

Matter exhibition at Vancouver Art Gallery, July 9 – Oct. 10, 2016 Bharti Kher, Virus VII, 2016, Photo: Megan Hill-Carol Vancouver Art Gallery

It is a stunning piece that almost seems to vibrate and is a fitting and sensual entry to the show.

For an alternative experience of the Kher show, there’s Robin Laurence’s July 6, 2016 preview titled: Bharti Kher’s hybrid vision merges humans with animals to address politics, sociology, and love for the Georgia Straight. Unexpectedly (for me), the first piece she sees is the heart,

The first artwork visitors will see when they enter Bharti Kher’s thoughtful and provocative exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery is a life-size sculpture of the heart of a blue sperm whale. The largest creature that now exists on our planet, the blue whale possesses a heart that is also the biggest in the world—the size, the artist says, of a small car. Kher’s realistic, cast-resin depiction of the organ’s two massive chambers, enormous aorta, and branching blood vessels is a work of weird grandeur.

To some, it might suggest an environmental message, a monument to a creature slaughtered by the hundreds of thousands in the 19th century and threatened in our own age by pollution and rising ocean temperatures. The artist, however, says the work is about the nature of love, and its title, An Absence of Assignable Cause, evokes the irrationality of that most vaunted and lamented emotion.

“More things have been written about love and all the ways around it,” she says. “I thought it would be interesting to talk about it using an animal as a metaphor.”

Picasso: The Artist and His Muses

Never having been a big fan of Pablo Picasso’s, I wouldn’t have made a special effort to see the VAG’s Picasso: The Artist and His Muses exhibition (June 11 – Oct. 2, 2016) but since I was already on premise for the Kher exhibit, it seemed to foolish to pass up the opportunity.

The show focuses on six women, his relationship with them, and how his art was affected by those relationships.

His most widely known images of women are those with the distorted features and extra or missing eyes and ears such as this,

Pablo Picasso

Bust of a Woman (Dora Maar), 1938

oil on canvas

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Gift of Joseph H. Hirshhorn, 1966

© Picasso Estate/SODRAC (2016)

Photo: Cathy Carver

These images have always left me cold. Seeing them in real life didn’t make that big a difference although I hadn’t fully appreciated their vibrancy having previously seen reproductions only. I did say I’m not a fan and that is especially true of the images of women most often seen. The surprise in this show, are the naturalistic studies where one can appreciate his extraordinary technique even if one is inclined to shun his distorted women.

I mention this show only because its subject, women, has been the direct and indirect focus of this commentary. For an even more jaundiced view of this show, you can read Robin Laurence’s June 10, 2016 preview of the VAG exhibition,

Muse is such a curiously antiquated term. Divine woman breathing inspiration into the mind of the creative male? Really? Still, Picasso: The Artist and His Muses has a more visitor-friendly sound to it than “Picasso and the Women He Fucked and Painted”. Not that visitor-friendly titles are a necessity where Pablo Picasso exhibitions are concerned.

The mere name of the man—easily the most famous artist of the 20th century, whose personal myth is built as much on his prodigious womanizing as on his protean art-making—guarantees attendance. Irrespective of what’s on view. Irrespective, too, of the challenges his work might pose to contemporary critics.

Organized with Art Centre Basel in Switzerland, the Vancouver Art Gallery’s big-draw summer show includes some 60 paintings, drawings, sculptures, and prints ranging across the years 1905 to 1971. Borrowed from an international array of public and private collections, it is the most ambitious exhibition of Picasso works ever shown in Western Canada.

I recommend reading both of Laurence’s pieces before going to the exhibit.

Final words

It seems when it comes to contemporary art, beauty is transgressive. The distortions with which Picasso experimented seem to have taken root and, like bamboo, taken over. So, an artist risks being shunned if his/her works are intrinsically beautiful (Lohan). Alternatively, an artist can include it by stealth (Kher) so viewers do not experience it as the primary impression.

All of these artists’ exhibitions have in one fashion or another focused on women. Lohan’s material of choice, porcelain, referenced women’s work indirectly and resonated in a fascinating way with Kher’s teacup bearing goddess. While Lohan and Kher are interested in women’s experiences (dressing/undressing and ornamentation (Kher), women’s roles in society (Lohan), meanwhile, Picasso seems to have considered women as raw material for his work.