Researchers at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology pose an interesting question in a Dec. 8, 2016 news item on Nanowerk,

Does it really help to drive an electric car if the electricity you use to charge the batteries come from a coal mine in Germany, or if the batteries were manufactured in China using coal?

Researchers at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology’s Industrial Ecology Programme have looked at all of the environmental costs of electric vehicles to determine the cradle-to-grave environmental footprint of building and operating these vehicles.

Increasingly, researchers are examining not just immediate environmental impacts but the impact a product has throughout its life cycle as this Dec. 8, 2016 Norwegian University of Science and Technology press release on EurekAlert notes,

In the 6 December [2016] issue of Nature Nanotechnology, the researchers report on a model that can help guide developers as they consider new nanomaterials for batteries or fuel cells. The goal is to create the most environmentally sustainable vehicle fleet possible, which is no small challenge given that there are already an estimated 1 billion cars and light trucks on the world’s roads, a number that is expected to double by 2035.

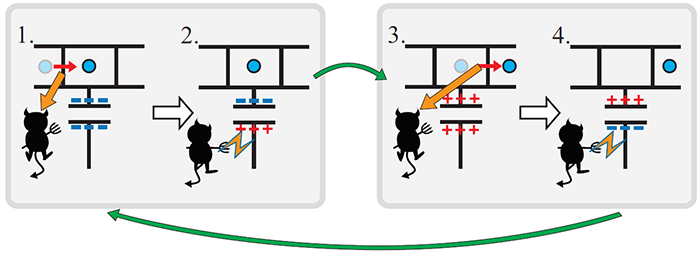

With this in mind, the researchers created an environmental life-cycle screening framework that looked at the environmental and other impacts of extraction, refining, synthesis, performance, durability and recyclablility of materials.

This allowed the researchers to evaluate the most promising nanomaterials for lithium-ion batteries (LIB) and proton exchange membrane hydrogen fuel cells (PEMFC) as power sources for electric vehicles. “Our analysis of the current situation clearly outlines the challenge,” the researchers wrote. “The materials with the best potential environmental profiles during the material extraction and production phase…. often present environmental disadvantages during their use phase… and vice versa.”

The hope is that by identifying all the environmental costs of different materials used to build electric cars, designers and engineers can “make the right design trade-offs that optimize LIB and PEMFC nanomaterials for EV usage towards mitigating climate change,” the authors wrote.

They encouraged material scientists and those who conduct life-cycle assessments to work together so that electric cars can be a key contributor to mitigating the effects of transportation on climate change.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

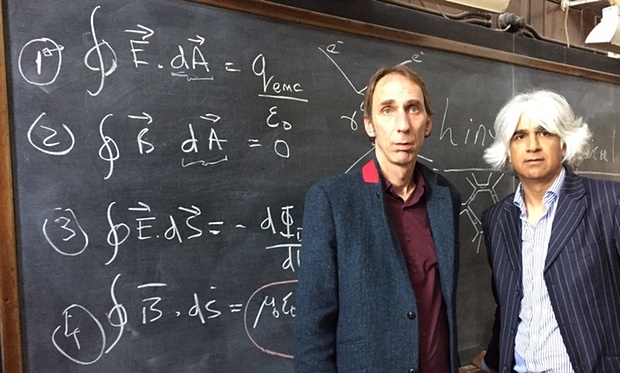

Nanotechnology for environmentally sustainable electromobility by Linda Ager-Wick Ellingsen, Christine Roxanne Hung, Guillaume Majeau-Bettez, Bhawna Singh, Zhongwei Chen, M. Stanley Whittingham, & Anders Hammer Strømman. Nature Nanotechnology 11, 1039–1051 (2016) doi:10.1038/nnano.2016.237 Published online 06 December 2016 Corrected online 14 December 2016

This paper is behind a paywall.

![Original manuscript of Maxwell’s seminal paper Photograph: Jon Butterworth/Royal Society [downloaded from http://www.theguardian.com/science/life-and-physics/2015/nov/22/maxwells-equations-150-years-of-light]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/MaxwellsUnificationTheory.jpg)

![The technology may lead to more powerful weapons, energy savings and reduced crew numbers [Downloaded from http://www.buffalo.edu/news/releases/2015/07/021.html]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/USNavyShip.jpg)