Technology is transforming key industries in B.C. and around the globe at an unprecedented pace.

From natural resources and agriculture to health and digital media, the second #BCTECH Summit returns with Microsoft as title sponsor, and will explore how tech is impacting every part of B.C.’s economy and changing lives.

Presented by the Province and the BC Innovation Council, B.C.͛s largest tech event will arm attendees with the tools to propel their companies to the next level, establish valuable business connections and inspire students to pursue careers in technology. From innovations in precision health, autonomous vehicles and customer experience, to emerging ideas in cleantech, agritech and aerospace, the #BCTECH Summit will showcase high-tech solutions to important local and global challenges.

New to the summit this year is the Future Realities Room, presented by Microsoft. It will be a dedicated space for B.C. companies to showcase their innovative augmented reality, virtual reality and mixed reality applications. From artificial intelligence to the internet-of-things, emerging technologies are disrupting industries and reshaping the path for future generations.

What attendees can expect at #BCTECH Summit 2017:

- Keynotes from thought leaders including Shahrzad Rafati of BroadbandTV, Ben Parr, author of Captivology, Microsoft and IBM.

- Sector-specific deep dives from experts exploring the innovations transforming their industries and every part of B.C’s economy.

- Opportunities to connect with tech buyers, scouts and investors through B2B meetings and the Investment Showcase.

- Expanded Marketplace, Technology Showcase including Startup Square and Research Runway, and the Future Realities Room presented by Microsoft.

- Youth Innovation Day to expose grades 10-12 students to diverse career paths in the technology sector.

- Evening networking receptions and Techfest by Techvibes, a recruiting event that connects hiring companies with tech talent.

The two-day event is attracting regional, national and international attendees seeking solutions for their business, investment opportunities and talent in the province. The summit builds on the success of the inaugural summit this past January, which attracted global attention and exceeded its goal of 1,000 attendees with more than 3,500 people in attendance.

Thomas Tannert

BC Leadership Chair in Tall Wood Construction

University of Northern British Columbia

Thomas joined the University of Northern British Columbia in 2016 as BC Leadership Chair in Tall Wood Construction. He received his PhD from the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, a Master’s degree in Wood Science and Technology from the University of Bio-Bio in Chile, and a Civil Engineering degree from the Bauhaus-University Weimar in Germany.

Before coming to UNBC, Thomas worked on multi-disciplinary teams in Germany, Chile, and Switzerland and was Associate Chair in Wood Building Design and Construction at UBC. He is an expert in the development of design methods for timber joints and structures and the assessment and monitoring of timber structures.

Thomas is actively involved in fostering collaboration among timber design experts in industry and academia, and is a member on multiple international committees as well as the Canadian Standard Association technical committee CSA-O86 “Engineering design in wood”.

Sarah Applebaum

Director, Pangea Spark

Pangea Ventures

Sarah Applebaum is the Director of Pangaea Spark at Pangaea Ventures. Sarah is a member of the Young Private Capitalist Committee of the CVCA, advisory board member for the CIX Cleantech Conference, start up showcase review board for SXSW Eco and mentor to the Singularity University Labs Accelerator. She is the co-founder of TNT Events, a Vancouver-based organization that strives to create a more interconnected and multi-disciplinary innovation ecosystem.

Sarah holds an MBA from the Schulich School of Business and a BSc. from Dalhousie University.

Natalie Cartwright

Co-founder

Finn.ai

Nat is a co-founder of Finn.ai, a white-label virtual banking assistance, powered by artificial intelligence. Nat holds a Master of Public Health from Lund University and a Masters of Business Administration from IE Business School.

Before founding Finn.ai in 2014, Nat worked at the Global Fund, the largest global financing institution for HIV, tuberculosis and malaria programs, where she managed $250 million USD in investment to countries like Djibouti, South Sudan and Tajikistan.

Whether working in international development or in financial technology, Nat likes to act on the potential she sees for improvement and innovation.

Martin Monkman

Provincial Statistician & Director, BC Stats

Province of British Columbia

Since first joining BC Stats (British Columbia’s statistics bureau) in 1993, Martin has built a wide range of experience using data science to support evidence-based policy and business management decisions. Now the Provincial Statistician & Director at BC Stats, Martin leads a dynamic and innovative team of professional researchers in analyzing statistical information about the economic and social conditions of British Columbia and measuring public sector organizational performance.

Martin holds Bachelor of Science and Master of Arts degrees in Geography from the University of Victoria. He is a member of the Statistical Analysis Committee of the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR), and blogs about baseball statistics and data science using the statistical software R at bayesball.blogspot.com.

Loc Dao

Chief Digital Officer

National Film Board of Canada

Loc is a Canadian digital media creator and co-founder of the groundbreaking NFB Digital and CBC Radio 3 studios and their industry shifting bodies of work.

Loc recently became the chief digital officer (CDO) of the National Film Board of Canada, after serving as executive producer and creative technologist for the NFB Digital Studio in Vancouver since 2011. His NFB credits include the interactive documentaries Bear 71, Welcome to Pine Point, Circa 1948, Waterlife, The Last Hunt and Cardboard Crash VR which have been credited with inventing the new form of the interactive documentary.

In December 2011, Loc was named Canada’s Top Digital Producer for 2011 at the Digi Awards in Toronto. In addition, his CBC Radio 3 was one of the world’s first cross media success stories combining the award-winning CBC Radio 3 web magazine, terrestrial and satellite radio, podcasts and 3 user generated content sites that preceded MySpace and YouTube.

Janice Cheam

Co-founder, President & CEO

Neurio Technology Inc.

Janice is an entrepreneurial executive whose vision, commitment, and passion has been the driving force behind Neurio. Coming from over 7 years of utility experience, as the CEO of Neurio Technology, Janice has been working to help businesses promote energy efficiency and engagement among users for over a decade. Having seen a huge unmet need in the smart home market, she and her co-founders answered it by creating Neurio, a smart energy monitoring platform used by over 100,000 homes.

George Rubin

Vice-President, Business Development

General Fusion

George is the Vice-President of Business Development at General Fusion, a company transforming the world’s energy supply by developing the world’s first fusion power plant based on commercially viable technology.

Previously, George was a co-founder, Vice-President and subsequently President of Day4 Energy Inc., where he was instrumental to developing the solar company’s strategic vision and was directly responsible for execution of the corporate development plan. Following his time at Day4, George founded Pacific Surf Partners and served as its Managing Director. In 2016 he joined General Fusion to develop and coordinate relationships in the business and research communities.

A graduate of Moscow State University with a Masters Degree in Quantum Radio Physics, and a British Columbia Institute of Technology graduate with a Diploma in Financial Management and a Bachelor Degree in Accounting, George combines his knowledge of science and business with the experience of over a decade in the cleantech industry.

Gareth Manderson

General Manager, BC Works

Rio Tinto

Gareth is the General Manager of Rio Tinto’s BC Works. In this role, he leads Rio Tinto Aluminium’s business in British Columbia, incorporating the operations of the Kitimat Smelter, Kemano Power Generation Facility and the Nechako Watershed. Prior to this, he led the Weipa Bauxite Business in Australia comprising of two mining operations, a port and the local town of Weipa.

Gareth has lived and worked in Australia, Canada, the USA and Italy, and completed assignments in a number of other countries. He has held accountability for business and operational leadership, consulting services, administrative and function support, and taken part in strategy development and due diligence work.

Gareth lives in Kitimat, British Columbia, with his wife and two children. He holds an Engineering Degree, a Master of Business Administration and is a Graduate of the Australian Institute of Company Directors.

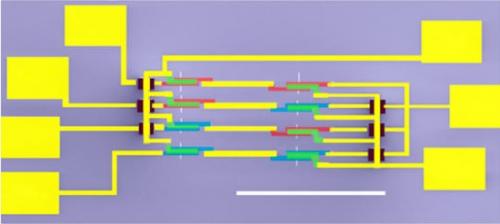

Stephanie Simmons

Canada Research Chair in Quantum Nanoelectronics & Assistant Professor

Simon Fraser University

Stephanie is an assistant professor in the Department of Physics at Simon Fraser University (SFU), where she leads the Silicon Quantum Technology research group. Stephanie earned a Ph.D. in Materials Science at Oxford University in 2011 as a Clarendon Scholar and a B.Math (Pure Mathematics and Mathematical Physics) from the University of Waterloo. She was a Postdoctoral Research Fellow of the Electrical Engineering Department at UNSW, Australia, and completed her Junior Research Fellowship from St. John’s College, Oxford University.

Stephanie joined SFU as a Canada Research Chair in Quantum Nanoelectronics in fall 2015 and is working to build a silicon-based quantum computer. Her work on silicon quantum technologies was awarded a Physics World Top Ten Breakthrough of the Year of 2013 and again in 2015, and has been covered by the New York Times, CBC, BBC, Scientific American, the New Scientist, and others.

I recently had the pleasure of hearing Simmons speak at the SFU President’s Faculty Lecture on Nov. 30, 2016. You can watch her talk here (the talk is approximately 1 hr. in length).

Getting back to #BCTECH Summit 2017, I’ve provided a small sample of the speakers. By my count there are 103 in total. BTW, kudos to the organizers’ skills and commitment as approximately 35% of the speakers are women. Yes, it could be better but compared to a lot of the meetings I’ve mentioned here, this statistic is a significant improvement. As for diversity, it seems to me that they could probably do a bit better there too.