A May 30, 2016 news item on phys.org introduces a scientist with an intriguing approach to quantum computing,

Creating quantum computers which some people believe will be the next generation of computers, with the ability to outperform machines based on conventional technology—depends upon harnessing the principles of quantum mechanics, or the physics that governs the behavior of particles at the subatomic scale. Entanglement—a concept that Albert Einstein once called “spooky action at a distance”—is integral to quantum computing, as it allows two physically separated particles to store and exchange information.

Stevan Nadj-Perge, assistant professor of applied physics and materials science, is interested in creating a device that could harness the power of entangled particles within a usable technology. However, one barrier to the development of quantum computing is decoherence, or the tendency of outside noise to destroy the quantum properties of a quantum computing device and ruin its ability to store information.

Nadj-Perge, who is originally from Serbia, received his undergraduate degree from Belgrade University and his PhD from Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. He received a Marie Curie Fellowship in 2011, and joined the Caltech Division of Engineering and Applied Science in January after completing postdoctoral appointments at Princeton and Delft.

He recently talked with us about how his experimental work aims to resolve the problem of decoherence.

A May 27, 2016 California Institute of Technology (CalTech) news release by Jessica Stoller-Conrad, which originated the news item, proceeds with a question and answer format,

What is the overall goal of your research?

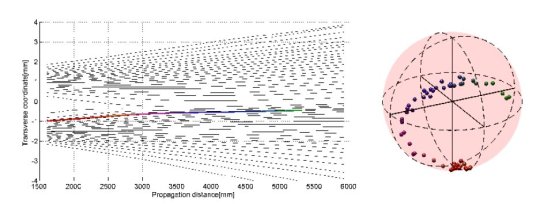

A large part of my research is focused on finding ways to store and process quantum information. Typically, if you have a quantum system, it loses its coherent properties—and therefore, its ability to store quantum information—very quickly. Quantum information is very fragile and even the smallest amount of external noise messes up quantum states. This is true for all quantum systems. There are various schemes that tackle this problem and postpone decoherence, but the one that I’m most interested in involves Majorana fermions. These particles were proposed to exist in nature almost eighty years ago but interestingly were never found.

Relatively recently theorists figured out how to engineer these particles in the lab. It turns out that, under certain conditions, when you combine certain materials and apply high magnetic fields at very cold temperatures, electrons will form a state that looks exactly as you would expect from Majorana fermions. Furthermore, such engineered states allow you to store quantum information in a way that postpones decoherence.

How exactly is quantum information stored using these Majorana fermions?

The fascinating property of these particles is that they always come in pairs. If you can store information in a pair of Majorana fermions it will be protected against all of the usual environmental noise that affects quantum states of individual objects. The information is protected because it is not stored in a single particle but in the pair itself. My lab is developing ways to engineer nanodevices which host Majorana fermions. Hopefully one day our devices will find applications in quantum computing.

Why did you want to come to Caltech to do this work?

The concept of engineered Majorana fermions and topological protection was, to a large degree, conceived here at Caltech by Alexei Kiteav [Ronald and Maxine Linde Professor of Theoretical Physics and Mathematics] who is in the physics department. A couple of physicists here at Caltech, Gil Refeal [professor of theoretical physics and executive officer of physics] and Jason Alicea [professor of theoretical physics], are doing theoretical work that is very relevant for my field.

Do you have any collaborations planned here?

Nothing formal, but I’ve been talking a lot with Gil and Jason. A student of mine also uses resources in the lab of Harry Atwater [Howard Hughes Professor of Applied Physics and Materials Science and director of the Joint Center for Artificial Photosynthesis], who has experience with materials that are potentially useful for our research.

How does that project relate to your lab’s work?

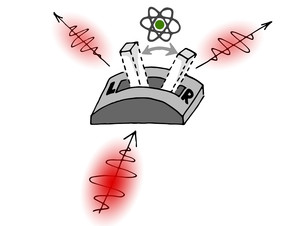

There are two-dimensional, or 2-D, materials that are basically very thin sheets of atoms. Graphene [emphasis mine]—a single layer of carbon atoms—is one example, but you can create single layer sheets of atoms with many materials. Harry Atwater’s group is working on solar cells made of a 2-D material. We are thinking of using the same materials and combining them with superconductors—materials that can conduct electricity without releasing heat, sound, or any other form of energy—in order to produce Majorana fermions.

How do you do that?

There are several proposed ways of using 2-D materials to create Majorana fermions. The majority of these materials have a strong spin-orbit coupling—an interaction of a particle’s spin with its motion—which is one of the key ingredients for creating Majoranas. Also some of the 2-D materials can become superconductors at low temperatures. One of the ideas that we are seriously considering is using a 2-D material as a substrate on which we could build atomic chains that will host Majorana fermions.

What got you interested in science when you were young?

I don’t come from a family of scientists; my father is an engineer and my mother is an administrative worker. But my father first got me interested in science. As an engineer, he was always solving something and he brought home some of the problems he was working. I worked with him and picked it up at an early age.

How are you adjusting to life in California?

Well, I like being outdoors, and here we have the mountains and the beach and it’s really amazing. The weather here is so much better than the other places I’ve lived. If you want to get the impression of what the weather in the Netherlands is like, you just replace the number of sunny days here with the number of rainy days there.

I wish Stevan Nadj-Perge good luck!