The days when you went cruising to ‘get away from it all’ seem to have passed (if they ever really existed) with the introduction of wearable technology that will register your every preference and make life easier according to Cliff Kuang’s Oct. 19, 2017 article for Fast Company,

This month [October 2017], the 141,000-ton Regal Princess will push out to sea after a nine-figure revamp of mind-boggling scale. Passengers won’t be greeted by new restaurants, swimming pools, or onboard activities, but will instead step into a future augured by the likes of Netflix and Uber, where nearly everything is on demand and personally tailored. An ambitious new customization platform has been woven into the ship’s 19 passenger decks: some 7,000 onboard sensors and 4,000 “guest portals” (door-access panels and touch-screen TVs), all of them connected by 75 miles of internal cabling. As the Carnival-owned ship cruises to Nassau, Bahamas, and Grand Turk, its 3,500 passengers will have the option of carrying a quarter-size device, called the Ocean Medallion, which can be slipped into a pocket or worn on the wrist and is synced with a companion app.

The platform will provide a new level of service for passengers; the onboard sensors record their tastes and respond to their movements, and the app guides them around the ship and toward activities aligned with their preferences. Carnival plans to roll out the platform to another seven ships by January 2019. Eventually, the Ocean Medallion could be opening doors, ordering drinks, and scheduling activities for passengers on all 102 of Carnival’s vessels across 10 cruise lines, from the mass-market Princess ships to the legendary ocean liners of Cunard.

Kuang goes on to explain the reasoning behind this innovation,

The Ocean Medallion is Carnival’s attempt to address a problem that’s become increasingly vexing to the $35.5 billion cruise industry. Driven by economics, ships have exploded in size: In 1996, Carnival Destiny was the world’s largest cruise ship, carrying 2,600 passengers. Today, Royal Caribbean’s MS Harmony of the Seas carries up to 6,780 passengers and 2,300 crew. Larger ships expend less fuel per passenger; the money saved can then go to adding more amenities—which, in turn, are geared to attracting as many types of people as possible. Today on a typical ship you can do practically anything—from attending violin concertos to bungee jumping. And that’s just onboard. Most of a cruise is spent in port, where each day there are dozens of experiences available. This avalanche of choice can bury a passenger. It has also made personalized service harder to deliver. …

Kuang also wrote this brief description of how the technology works from the passenger’s perspective in an Oct. 19, 2017 item for Fast Company,

1. Pre-trip

On the web or on the app, you can book experiences, log your tastes and interests, and line up your days. That data powers the recommendations you’ll see. The Ocean Medallion arrives by mail and becomes the key to ship access.

2. Stateroom

When you draw near, your cabin-room door unlocks without swiping. The room’s unique 43-inch TV, which doubles as a touch screen, offers a range of Carnival’s bespoke travel shows. Whatever you watch is fed into your excursion suggestions.

3. Food

When you order something, sensors detect where you are, allowing your server to find you. Your allergies and preferences are also tracked, and shape the choices you’re offered. In all, the back-end data has 45,000 allergens tagged and manages 250,000 drink combinations.

4. Activities

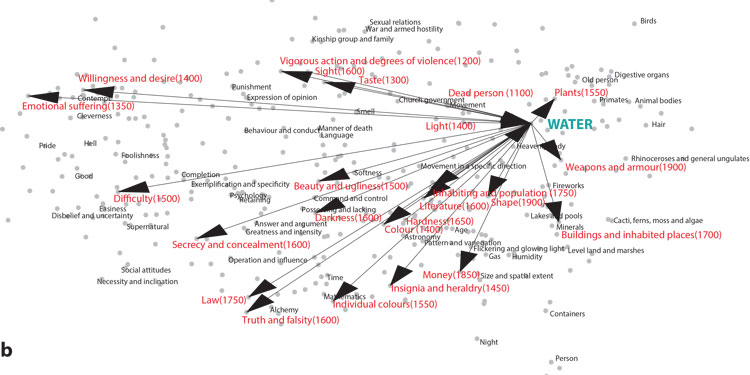

The right algorithms can go beyond suggesting wines based on previous orders. Carnival is creating a massive semantic database, so if you like pricey reds, you’re more apt to be guided to a violin concerto than a limbo competition. Your onboard choices—the casino, the gym, the pool—inform your excursion recommendations.

In Kuang’s Oct. 19, 2017 article he notes that the cruise ship line is putting a lot of effort into retraining their staff and emphasizing the ‘soft’ skills that aren’t going to be found in this iteration of the technology. No mention is made of whether or not there will be reductions in the number of staff members on this cruise ship nor is the possibility that ‘soft’ skills may in the future be incorporated into this technological marvel.

Personalization/customization is increasingly everywhere

How do you feel about customized news feeds? As it turns out, this is not a rhetorical question as Adrienne LaFrance notes in her Oct. 19, 2017 article for The Atlantic (Note: Links have been removed),

…

Today, a Google search for news runs through the same algorithmic filtration system as any other Google search: A person’s individual search history, geographic location, and other demographic information affects what Google shows you. Exactly how your search results differ from any other person’s is a mystery, however. Not even the computer scientists who developed the algorithm could precisely reverse engineer it, given the fact that the same result can be achieved through numerous paths, and that ranking factors—deciding which results show up first—are constantly changing, as are the algorithms themselves.

We now get our news in real time, on demand, tailored to our interests, across multiple platforms, without knowing just how much is actually personalized. It was technology companies like Google and Facebook, not traditional newsrooms, that made it so. But news organizations are increasingly betting that offering personalized content can help them draw audiences to their sites—and keep them coming back.

Personalization extends beyond how and where news organizations meet their readers. Already, smartphone users can subscribe to push notifications for the specific coverage areas that interest them. On Facebook, users can decide—to some extent—which organizations’ stories they would like to appear in their news feeds. At the same time, devices and platforms that use machine learning to get to know their users will increasingly play a role in shaping ultra-personalized news products. Meanwhile, voice-activated artificially intelligent devices, such as Google Home and Amazon Echo, are poised to redefine the relationship between news consumers and the news [emphasis mine].

While news personalization can help people manage information overload by making individuals’ news diets unique, it also threatens to incite filter bubbles and, in turn, bias [emphasis mine]. This “creates a bit of an echo chamber,” says Judith Donath, author of The Social Machine: Designs for Living Online and a researcher affiliated with Harvard University ’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society. “You get news that is designed to be palatable to you. It feeds into people’s appetite of expecting the news to be entertaining … [and] the desire to have news that’s reinforcing your beliefs, as opposed to teaching you about what’s happening in the world and helping you predict the future better.”

…

Still, algorithms have a place in responsible journalism. “An algorithm actually is the modern editorial tool,” says Tamar Charney, the managing editor of NPR One, the organization’s customizable mobile-listening app. A handcrafted hub for audio content from both local and national programs as well as podcasts from sources other than NPR, NPR One employs an algorithm to help populate users’ streams with content that is likely to interest them. But Charney assures there’s still a human hand involved: “The whole editorial vision of NPR One was to take the best of what humans do and take the best of what algorithms do and marry them together.” [emphasis mine]

…

The skimming and diving Charney describes sounds almost exactly like how Apple and Google approach their distributed-content platforms. With Apple News, users can decide which outlets and topics they are most interested in seeing, with Siri offering suggestions as the algorithm gets better at understanding your preferences. Siri now has have help from Safari. The personal assistant can now detect browser history and suggest news items based on what someone’s been looking at—for example, if someone is searching Safari for Reykjavík-related travel information, they will then see Iceland-related news on Apple News. But the For You view of Apple News isn’t 100 percent customizable, as it still spotlights top stories of the day, and trending stories that are popular with other users, alongside those curated just for you.

Similarly, with Google’s latest update to Google News, readers can scan fixed headlines, customize sidebars on the page to their core interests and location—and, of course, search. The latest redesign of Google News makes it look newsier than ever, and adds to many of the personalization features Google first introduced in 2010. There’s also a place where you can preprogram your own interests into the algorithm.

Google says this isn’t an attempt to supplant news organizations, nor is it inspired by them. The design is rather an embodiment of Google’s original ethos, the product manager for Google News Anand Paka says: “Just due to the deluge of information, users do want ways to control information overload. In other words, why should I read the news that I don’t care about?” [emphasis mine]

…

Meanwhile, in May [2017?], Google briefly tested a personalized search filter that would dip into its trove of data about users with personal Google and Gmail accounts and include results exclusively from their emails, photos, calendar items, and other personal data related to their query. [emphasis mine] The “personal” tab was supposedly “just an experiment,” a Google spokesperson said, and the option was temporarily removed, but seems to have rolled back out for many users as of August [2017?].

Now, Google, in seeking to settle a class-action lawsuit alleging that scanning emails to offer targeted ads amounts to illegal wiretapping, is promising that for the next three years it won’t use the content of its users’ emails to serve up targeted ads in Gmail. The move, which will go into effect at an unspecified date, doesn’t mean users won’t see ads, however. Google will continue to collect data from users’ search histories, YouTube, and Chrome browsing habits, and other activity.

The fear that personalization will encourage filter bubbles by narrowing the selection of stories is a valid one, especially considering that the average internet user or news consumer might not even be aware of such efforts. Elia Powers, an assistant professor of journalism and news media at Towson University in Maryland, studied the awareness of news personalization among students after he noticed those in his own classes didn’t seem to realize the extent to which Facebook and Google customized users’ results. “My sense is that they didn’t really understand … the role that people that were curating the algorithms [had], how influential that was. And they also didn’t understand that they could play a pretty active role on Facebook in telling Facebook what kinds of news they want them to show and how to prioritize [content] on Google,” he says.

The results of Powers’s study, which was published in Digital Journalism in February [2017], showed that the majority of students had no idea that algorithms were filtering the news content they saw on Facebook and Google. When asked if Facebook shows every news item, posted by organizations or people, in a users’ newsfeed, only 24 percent of those surveyed were aware that Facebook prioritizes certain posts and hides others. Similarly, only a quarter of respondents said Google search results would be different for two different people entering the same search terms at the same time. [emphasis mine; Note: Respondents in this study were students.]

This, of course, has implications beyond the classroom, says Powers: “People as news consumers need to be aware of what decisions are being made [for them], before they even open their news sites, by algorithms and the people behind them, and also be able to understand how they can counter the effects or maybe even turn off personalization or make tweaks to their feeds or their news sites so they take a more active role in actually seeing what they want to see in their feeds.”

On Google and Facebook, the algorithm that determines what you see is invisible. With voice-activated assistants, the algorithm suddenly has a persona. “We are being trained to have a relationship with the AI,” says Amy Webb, founder of the Future Today Institute and an adjunct professor at New York University Stern School of Business. “This is so much more catastrophically horrible for news organizations than the internet. At least with the internet, I have options. The voice ecosystem is not built that way. It’s being built so I just get the information I need in a pleasing way.”

…

LaFrance’s article is thoughtful and well worth reading in its entirety. Now, onto some commentary.

Loss of personal agency

I have been concerned for some time about the increasingly dull results I get from a Google search and while I realize the company has been gathering information about me via my searches , supposedly in service of giving me better searches, I had no idea how deeply the company can mine for personal data. It makes me wonder what would happen if Google and Facebook attempted a merger.

More cogently, I rather resent the search engines and artificial intelligence agents (e.g. Facebook bots) which have usurped my role as the arbiter of what interests me, in short, my increasing loss of personal agency.

I’m also deeply suspicious of what these companies are going to do with my data. Will it be used to manipulate me in some way? Presumably, the data will be sold and used for some purpose. In the US, they have married electoral data with consumer data as Brent Bambury notes in an Oct. 13, 2017 article for his CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) Radio show,

How much of your personal information circulates in the free-market ether of metadata? It could be more than you imagine, and it might be enough to let others change the way you vote.

A data firm that specializes in creating psychological profiles of voters claims to have up to 5,000 data points on 220 million Americans. Cambridge Analytica has deep ties to the American right and was hired by the campaigns of Ben Carson, Ted Cruz and Donald Trump.

During the U.S. election, CNN called them “Donald Trump’s mind readers” and his secret weapon.

…

David Carroll is a Professor at the Parsons School of Design in New York City. He is one of the millions of Americans profiled by Cambridge Analytica and he’s taking legal action to find out where the company gets its masses of data and how they use it to create their vaunted psychographic profiles of voters.

On Day 6 [Banbury’s CBC radio programme], he explained why that’s important.

“They claim to have figured out how to project our voting behavior based on our consumer behavior. So it’s important for citizens to be able to understand this because it would affect our ability to understand how we’re being targeted by campaigns and how the messages that we’re seeing on Facebook and television are being directed at us to manipulate us.” [emphasis mine]

…

The parent company of Cambridge Analytica, SCL Group, is a U.K.-based data operation with global ties to military and political activities. David Carroll says the potential for sharing personal data internationally is a cause for concern.

“It’s the first time that this kind of data is being collected and transferred across geographic boundaries,” he says.

But that also gives Carroll an opening for legal action. An individual has more rights to access their personal information in the U.K., so that’s where he’s launching his lawsuit.

…

Reports link Michael Flynn, briefly Trump’s National Security Adviser, to SCL Group and indicate that former White House strategist Steve Bannon is a board member of Cambridge Analytica. Billionaire Robert Mercer, who has underwritten Bannon’s Breitbart operations and is a major Trump donor, also has a significant stake in Cambridge Analytica.

In the world of data, Mercer’s credentials are impeccable.

“He is an important contributor to the field of artificial intelligence,” says David Carroll.

“His work at IBM is seminal and really important in terms of the foundational ideas that go into big data analytics, so the relationship between AI and big data analytics. …

Banbury’s piece offers a lot more, including embedded videos, than I’ve not included in that excerpt but I also wanted to include some material from Carole Cadwalladr’s Oct. 1, 2017 Guardian article about Carroll and his legal fight in the UK,

“There are so many disturbing aspects to this. One of the things that really troubles me is how the company can buy anonymous data completely legally from all these different sources, but as soon as it attaches it to voter files, you are re-identified. It means that every privacy policy we have ignored in our use of technology is a broken promise. It would be one thing if this information stayed in the US, if it was an American company and it only did voter data stuff.”

But, he [Carroll] argues, “it’s not just a US company and it’s not just a civilian company”. Instead, he says, it has ties with the military through SCL – “and it doesn’t just do voter targeting”. Carroll has provided information to the Senate intelligence committee and believes that the disclosures mandated by a British court could provide evidence helpful to investigators.

Frank Pasquale, a law professor at the University of Maryland, author of The Black Box Society and a leading expert on big data and the law, called the case a “watershed moment”.

“It really is a David and Goliath fight and I think it will be the model for other citizens’ actions against other big corporations. I think we will look back and see it as a really significant case in terms of the future of algorithmic accountability and data protection. …

Nobody is discussing personal agency directly but if you’re only being exposed to certain kinds of messages then your personal agency has been taken from you. Admittedly we don’t have complete personal agency in our lives but AI along with the data gathering done online and increasingly with wearable and smart technology means that another layer of control has been added to your life and it is largely invisible. After all, the students in Elia Powers’ study didn’t realize their news feeds were being pre-curated.