On first glance it looked like a set of matches. If there were more dimension, this could also have been a set pencils but no,

An October 23, 2023 news item on Nanowerk introduces research into a new approach to optical neural networks

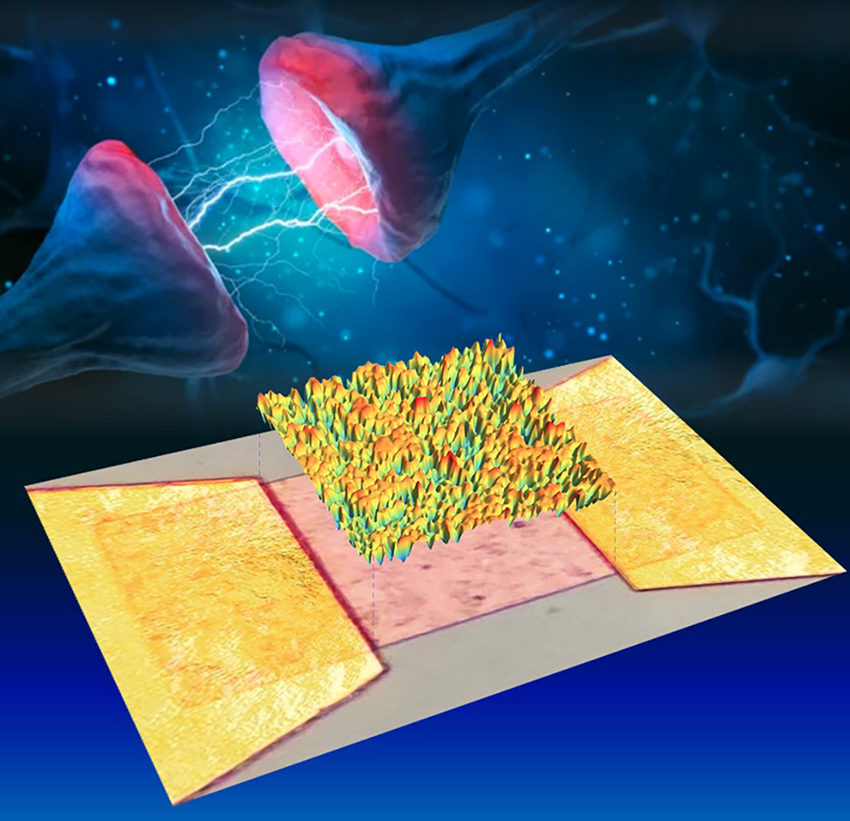

A team of researchers headed by physicists Prof. Wolfram Pernice and Prof. Martin Salinga and computer specialist Prof. Benjamin Risse, all from the University of Münster, has developed a so-called event-based architecture, using photonic processors. In a similar way to the brain, this makes possible the continuous adaptation of the connections within the neural network.

Key Takeaways

Researchers have created a new computing architecture that mimics biological neural networks, using photonic processors for data transportation and processing.

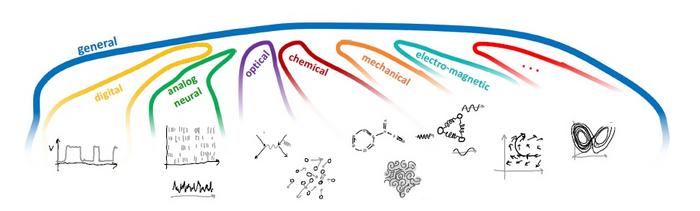

The new system enables continuous adaptation of connections within the neural network, crucial for learning processes. This is known as both synaptic and structural plasticity.

Unlike traditional studies, the connections or synapses in this photonic neural network are not hardware-based but are coded based on optical pulse properties, allowing for a single chip to hold several thousand neurons.

Light-based processors in this system offer a much higher bandwidth and lower energy consumption compared to traditional electronic processors.

The researchers successfully tested the system using an evolutionary algorithm to differentiate between German and English texts based on vowel count, highlighting its potential for rapid and energy-efficient AI applications.

The Research

Modern computer models – for example for complex, potent AI applications – push traditional digital computer processes to their limits.

…

The person who edited the original press release, which is included in the news item in the above, is not credited.

Here’s the unedited original October 23, 2023 University of Münster press release (also on EurekAlert)

Modern computer models – for example for complex, potent AI applications – push traditional digital computer processes to their limits. New types of computing architecture, which emulate the working principles of biological neural networks, hold the promise of faster, more energy-efficient data processing. A team of researchers has now developed a so-called event-based architecture, using photonic processors with which data are transported and processed by means of light. In a similar way to the brain, this makes possible the continuous adaptation of the connections within the neural network. This changeable connections are the basis for learning processes. For the purposes of the study, a team working at Collaborative Research Centre 1459 (“Intelligent Matter”) – headed by physicists Prof. Wolfram Pernice and Prof. Martin Salinga and computer specialist Prof. Benjamin Risse, all from the University of Münster – joined forces with researchers from the Universities of Exeter and Oxford in the UK. The study has been published in the journal “Science Advances”.

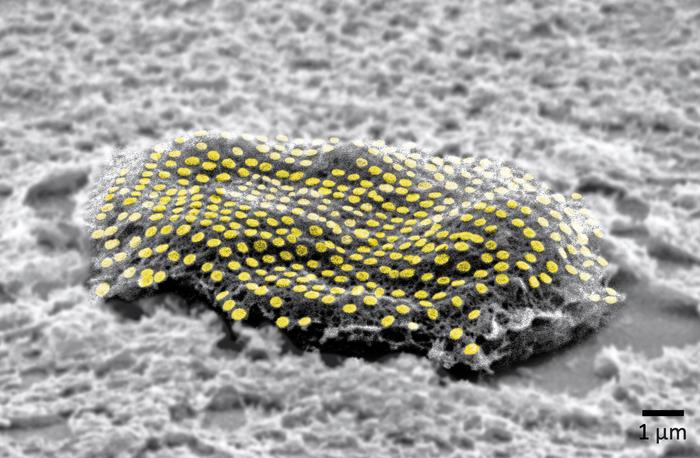

What is needed for a neural network in machine learning are artificial neurons which are activated by external excitatory signals, and which have connections to other neurons. The connections between these artificial neurons are called synapses – just like the biological original. For their study, the team of researchers in Münster used a network consisting of almost 8,400 optical neurons made of waveguide-coupled phase-change material, and the team showed that the connection between two each of these neurons can indeed become stronger or weaker (synaptic plasticity), and that new connections can be formed, or existing ones eliminated (structural plasticity). In contrast to other similar studies, the synapses were not hardware elements but were coded as a result of the properties of the optical pulses – in other words, as a result of the respective wavelength and of the intensity of the optical pulse. This made it possible to integrate several thousand neurons on one single chip and connect them optically.

In comparison with traditional electronic processors, light-based processors offer a significantly higher bandwidth, making it possible to carry out complex computing tasks, and with lower energy consumption. This new approach consists of basic research. “Our aim is to develop an optical computing architecture which in the long term will make it possible to compute AI applications in a rapid and energy-efficient way,” says Frank Brückerhoff-Plückelmann, one of the lead authors.

Methodology: The non-volatile phase-change material can be switched between an amorphous structure and a crystalline structure with a highly ordered atomic lattice. This feature allows permanent data storage even without an energy supply. The researchers tested the performance of the neural network by using an evolutionary algorithm to train it to distinguish between German and English texts. The recognition parameter they used was the number of vowels in the text.

The researchers received financial support from the German Research Association, the European Commission and “UK Research and Innovation”.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Event-driven adaptive optical neural network by Frank Brückerhoff-Plückelmann, Ivonne Bente, Marlon Becker, Niklas Vollmar, Nikolaos Farmakidis, Emma Lomonte, Francesco Lenzini, C. David Wright, Harish Bhaskaran, Martin Salinga, Benjamin Risse, and Wolfram H. P. Pernice. Science Advances 20 Oct 2023 Vol 9, Issue 42 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adi9127

This paper is open access.