The research was published online May 2014 and in a July 2014 print version, which seems a long time ago now but there’s a renewed interest in attracting attention for this work. A Dec. 17, 2014 news item on phys.org describes this proposed water purification technology from Singapore’s A*STAR (Agency for Science Technology and Research), Note: Links have been removed,

A new catalyst could have dramatic environmental benefits if it can live up to its potential, suggests research from Singapore. A*STAR researchers have produced a catalyst with gold-nanoparticle antennas that can improve water quality in daylight and also generate hydrogen as a green energy source.

This water purification technology was developed by He-Kuan Luo, Andy Hor and colleagues from the A*STAR Institute of Materials Research and Engineering (IMRE). “Any innovative and benign technology that can remove or destroy organic pollutants from water under ambient conditions is highly welcome,” explains Hor, who is executive director of the IMRE and also affiliated with the National University of Singapore.

A Dec. 17, 2014 A*STAR research highlight, which originated the news item, describes the photocatalytic process the research team developed and tested,

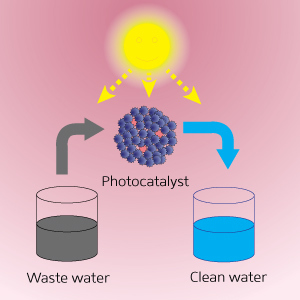

Photocatalytic materials harness sunlight to create electrical charges, which provide the energy needed to drive chemical reactions in molecules attached to the catalyst’s surface. In addition to decomposing harmful molecules in water, photocatalysts are used to split water into its components of oxygen and hydrogen; hydrogen can then be employed as a green energy source.

Hor and his team set out to improve an existing catalyst. Oxygen-based compounds such as strontium titanate (SrTiO3) look promising, as they are robust and stable materials and are suitable for use in water. One of the team’s innovations was to enhance its catalytic activity by adding small quantities of the metal lanthanum, which provides additional usable electrical charges.

Catalysts also need to capture a sufficient amount of sunlight to catalyze chemical reactions. So to enable the photocatalyst to harvest more light, the scientists attached gold nanoparticles to the lanthanum-doped SrTiO3 microspheres (see image). These gold nanoparticles are enriched with electrons and hence act as antennas, concentrating light to accelerate the catalytic reaction.

The porous structure of the microspheres results in a large surface area, as it provides more binding space for organic molecules to dock to. A single gram of the material has a surface area of about 100 square meters. “The large surface area plays a critical role in achieving a good photocatalytic activity,” comments Luo.

To demonstrate the efficiency of these catalysts, the researchers studied how they decomposed the dye rhodamine B in water. Within four hours of exposure to visible light 92 per cent of the dye was gone, which is much faster than conventional catalysts that lack gold nanoparticles.

These microparticles can also be used for water splitting, says Luo. The team showed that the microparticles with gold nanoparticles performed better in water-splitting experiments than those without, further highlighting the versatility and effectiveness of these microspheres.

The researchers have provided an illustration of the process,

Improved photocatalyst microparticles containing gold nanoparticles can be used to purify water.

© 2014 A*STAR Institute of Materials Research and Engineering

Here’s a link to and a citation for the research paper,

Novel Au/La-SrTiO3 microspheres: Superimposed Effect of Gold Nanoparticles and Lanthanum Doping in Photocatalysis by Guannan Wang, Pei Wang, Dr. He-Kuan Luo, and Prof. T. S. Andy Hor. Chemistry – An Asian Journal Volume 9, Issue 7, pages 1854–1859, July 2014. Article first published online: 9 MAY 2014 DOI: 10.1002/asia.201402007

© 2014 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim

This article is behind a paywall.

![Subsea installations can get longer life-time with self-repairing materials. Illustration: SINTEF Energy [downloaded from http://gemini.no/en/2014/11/self-repairing-subsea-material/]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/SubseaInstallation-300x150.png)