Scientists used equipment at the Canadian Light Source (CLS; synchrotron in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada) in the quest for better glowing dots on your television (maybe computers and telephones, too?) screen. From an August 20, 2020 news item on Nanowerk,

There are many things quantum dots could do, but the most obvious place they could change our lives is to make the colours on our TVs and screens more pristine. Research using the Canadian Light Source (CLS) at the University of Saskatchewan is helping to bring this technology closer to our living rooms.

An August 19, 2020 CLS news release (also received via email) by Victoria Martinez, which originated the news item, explains what quantum dots are and fills in with technical details about this research,

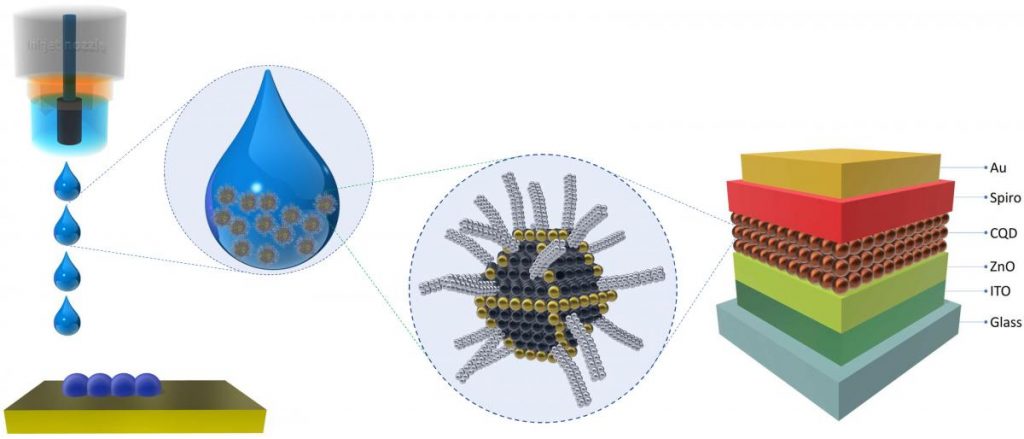

Quantum dots are nanocrystals that glow, a property that scientists have been working with to develop next-generation LEDs. When a quantum dot glows, it creates very pure light in a precise wavelength of red, blue or green. Conventional LEDs, found in our TV screens today, produce white light that is filtered to achieve desired colours, a process that leads to less bright and muddier colours.

Until now, blue-glowing quantum dots, which are crucial for creating a full range of colour, have proved particularly challenging for researchers to develop. However, University of Toronto (U of T) researcher Dr. Yitong Dong and collaborators have made a huge leap in blue quantum dot fluorescence, results they recently published in Nature Nanotechnology.

“The idea is that if you have a blue LED, you have everything. We can always down convert the light from blue to green and red,” says Dong. “Let’s say you have green, then you cannot use this lower-energy light to make blue.”

The team’s breakthrough has led to quantum dots that produce green light at an external quantum efficiency (EQE) of 22% and blue at 12.3%. The theoretical maximum efficiency is not far off at 25%, and this is the first blue perovskite LED reported as achieving an EQE higher than 10%.

The Science

Dong has been working in the field of quantum dots for two years in Dr. Edward Sargent’s research group at the U of T. This astonishing increase in efficiency took time, an unusual production approach, and overcoming several scientific hurdles to achieve.

CLS techniques, particularly GIWAXS [grazing incidence wide-angle X-ray scattering] on the HXMA beamline [hard X-ray micro-analysis (HXMA)], allowed the researchers to verify the structures achieved in their quantum dot films. This validated their results and helped clarify what the structural changes achieve in terms of LED performance.

“The CLS was very helpful. GIWAXS is a fascinating technique,” says Dong.

The first challenge was uniformity, important to ensuring a clear blue colour and to prevent the LED from moving towards producing green light.

“We used a special synthetic approach to achieve a very uniform assembly, so every single particle has the same size and shape. The overall film is nearly perfect and maintains the blue emission conditions all the way through,” says Dong.

Next, the team needed to tackle the charge injection needed to excite the dots into luminescence. Since the crystals are not very stable, they need stabilizing molecules to act as scaffolding and support them. These are typically long molecule chains, with up to 18 carbon-non-conductive molecules at the surface, making it hard to get the energy to produce light.

“We used a special surface structure to stabilize the quantum dot. Compared to the films made with long chain molecules capped quantum dots, our film has 100 times higher conductivity, sometimes even 1000 times higher.”

This remarkable performance is a key benchmark in bringing these nanocrystal LEDs to market. However, stability remains an issue and quantum dot LEDs suffer from short lifetimes. Dong is excited about the potential for the field and adds, “I like photons, these are interesting materials, and, well, these glowing crystals are just beautiful.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Bipolar-shell resurfacing for blue LEDs based on strongly confined perovskite quantum dots by Yitong Dong, Ya-Kun Wang, Fanglong Yuan, Andrew Johnston, Yuan Liu, Dongxin Ma, Min-Jae Choi, Bin Chen, Mahshid Chekini, Se-Woong Baek, Laxmi Kishore Sagar, James Fan, Yi Hou, Mingjian Wu, Seungjin Lee, Bin Sun, Sjoerd Hoogland, Rafael Quintero-Bermudez, Hinako Ebe, Petar Todorovic, Filip Dinic, Peicheng Li, Hao Ting Kung, Makhsud I. Saidaminov, Eugenia Kumacheva, Erdmann Spiecker, Liang-Sheng Liao, Oleksandr Voznyy, Zheng-Hong Lu, Edward H. Sargent. Nature Nanotechnology volume 15, pages668–674(2020) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-020-0714-5 Published: 06 July 2020 Issue Date: August 2020

This paper is behind a paywall.

If you search “Edward Sargent,” he’s the last author listed in the citation, here on this blog, you will find a number of postings that feature work from his laboratory at the University of Toronto.