A May 24, 2023 news item on phys.org introduces organic-inorganic nanohybrids for optoelectronic devices,

When designing optoelectronic devices, such as solar cells, photocatalysts, and photodetectors, scientists usually prioritize materials that are stable and possess tunable properties. This allows them precise control over optical characteristics of the materials and ensures retention of their properties over time, despite varying environmental conditions.

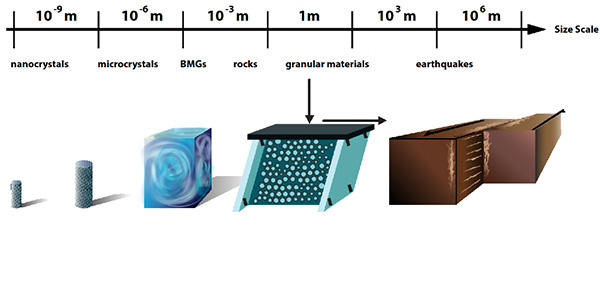

Organic-inorganic nanohybrids, which are made up of organic ligands attached to the surface of colloidal inorganic nanocrystals via coordinate bonds, are promising in this regard. They are known to exhibit enhanced stability owing to the formation of a protective layer by organic ligands around the reactive inorganic nanocrystal. However, the incorporation of organic ligands has been found to lower the conductivity and photon absorption efficiency of inorganic nanocrystals.

In a breakthrough study on ligand-nanocrystal interactions, researchers from Japan now demonstrate a quasi-reversible displacement of organic ligands on the surface of nanocrystals. Their findings, published in ACS Nano, provide a new perspective to the common belief that the organic ligands are anchored to the surface of the nanocrystals.

…

A May 22, 2023 Ritsumeikan University (Japan) press release (also on EurekAlert but published May 24, 2023), which originated the news item, provides more detail,

… The research team, led by Professor Yoichi Kobayashi from Ritsumeikan University, Japan, found that the coordination bond between perylene bisimide with a carboxyl group (PBI) and inorganic zinc sulfide (ZnS) nanocrystals can be reversibly displaced by exposing the material to visible light.

Shedding light on this novel behavior of organic-inorganic nanohybrids, Prof. Kobayashi says, “We explored the ligand properties of organic-inorganic nanohybrid systems by using perylene bisimide with a carboxyl group (PBI)-coordinated zinc sulfide (ZnS) NCs (PBI–ZnS) as a model system. Our findings provide the first example of photoinduced displacement of aromatic ligands with semiconductor nanocrystals.”

In their study, the researchers carried out both theoretical analysis and experimental investigations to understand the material’s unique photoinducible characteristics. They first conducted density functional theory calculations to study the structure and orbitals of PBI–ZnS ([PBI-Zn25S31]–) in both its ground and first excited states. Next, they performed time-resolved impulsive stimulated Raman spectroscopy to excite the sample with an ultrafast laser. This helped them analyze the corresponding Raman spectrum that revealed the nature of the excited state of PBI–ZnS.

The experimental observations and calculations showed that, upon photoexcitation, an electron is excited from the PBI molecule, and the corresponding “hole”(the vacancy formed due to the absence of the electron) rapidly moves from the aromatic ligand (PBI) to ZnS. This results in a long-lived, negatively-charged PBI ion that is displaced from the surface of the ZnS nanocrystal. Over time, however, the displaced ligands recombine with the surface defects of the ZnS nanocrystal, leading to a quasi-reversible photoinduced displacement of coordinated PBI. Notably, the dynamic behavior of coordinated ligand molecules observed in this study is different from that observed for typical photoinduced charge transfer processes in which the hole typically remains on the donor molecule, enabling it to recombine with the electron quickly.

Explaining the significance of these findings, Prof. Kobayashi says, “The precise understanding of ligand-nanocrystal interaction is important not only for fundamental nanoscience but also for developing advanced photofunctional materials using nanomaterials. These include photocatalysts for the decomposition of persistent chemicals using visible light and photoconductive microcircuit patterning for wearable devices.”

Indeed, the results of this study present a promising avenue for enhancing the tunability and functionality of inorganic materials with aromatic molecules. This, in turn, could significantly impact the field of fundamental nanoscience and photochemistry in the times to come.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Quasi-Reversible Photoinduced Displacement of Aromatic Ligands from Semiconductor Nanocrystals by Daisuke Yoshioka, Yusuke Yoneda, I-Ya Chang, Hikaru Kuramochi, Kim Hyeon-Deuk, and Yoichi Kobayashi. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 12, 11309–11317 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.2c12578 Publication Date:May 9, 2023 Copyright © 2023 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.