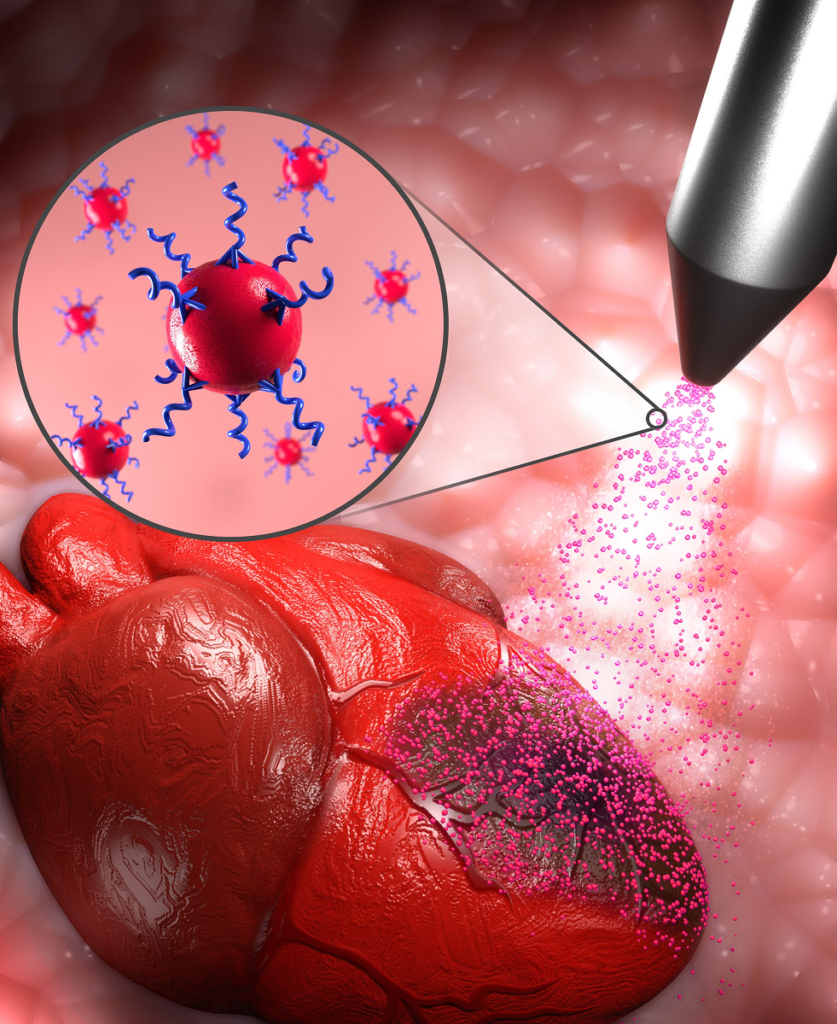

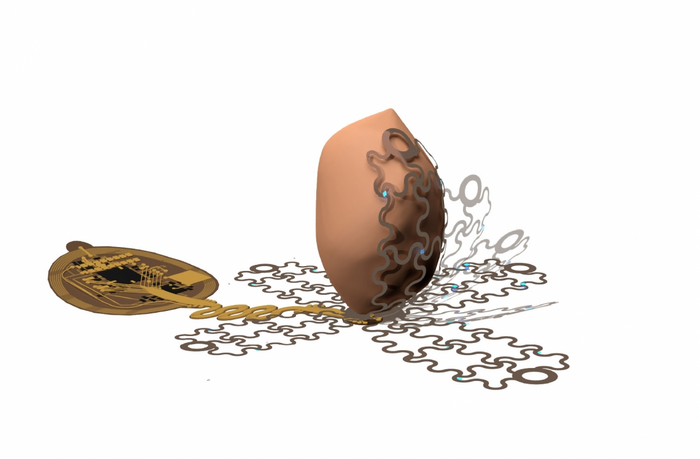

I think it looks more like a potato than a heart but it does illustrate how this new battery-free pacemaker would wrap around a heart,

An October 27, 2022 news item on ScienceDaily announces a technology that could make life much easier for people with pacemakers (Comment: In the image, that looks more like a potato than a heart, to me),

University of Arizona engineers lead a research team that is developing a new kind of pacemaker, which envelops the heart and uses precise targeting capabilities to bypass pain receptors and reduce patient discomfort.

…

An October 27, 2022 University of Arizona news release (also on EurekAlert) by Emily Dieckman, which originated the news item, explains the reasons for the research and provides some technical details (Note: Links have been removed),

Pacemakers are lifesaving devices that regulate the heartbeats of people with chronic heart diseases like atrial fibrillation and other forms of arrhythmia. However, pacemaker implantation is an invasive procedure, and the lifesaving pacing the devices provide can be extremely painful. Additionally, pacemakers can only be used to treat a few specific types of disease.

In a paper published Wednesday [October 26, 2022] in Science Advances, a University of Arizona-led team of researchers detail the workings of a wireless, battery-free pacemaker they designed that could be implanted with a less invasive procedure than currently possible and would cause patients less pain. The study was helmed by researchers in the Gutruf Lab, led by biomedical engineering assistant professor and Craig M. Berge Faculty Fellow Philipp Gutruf.

Currently available pacemakers work by implanting one or two leads, or points of contact, into the heart with hooks or screws. If the sensors on these leads detect a dangerous irregularity, they send an electrical shock through the heart to reset the beat.

“All of the cells inside the heart get hit at one time, including the pain receptors, and that’s what makes pacing or defibrillation painful,” Gutruf said. “It affects the heart muscle as a whole.”

The device Gutruf’s team has developed, which has not yet been tested in humans, would allow pacemakers to send much more targeted signals using a new digitally manufactured mesh design that encompasses the entire heart. The device uses light and a technique called optogenetics.

Optogenetics modifies cells, usually neurons, sensitive to light, then uses light to affect the behavior of those cells. This technique only targets cardiomyocytes, the cells of the muscle that trigger contraction and make up the beat of the heart. This precision will not only reduce pain for pacemaker patients by bypassing the heart’s pain receptors, it will also allow the pacemaker to respond to different kinds of irregularities in more appropriate ways. For example, during atrial fibrillation, the upper and lower chambers of the heart beat asynchronously, and a pacemaker’s role is to get the two parts back in line.

“Whereas right now, we have to shock the whole heart to do this, these new devices can do much more precise targeting, making defibrillation both more effective and less painful,” said Igor Efimov, professor of biomedical engineering and medicine at Northwestern University, where the devices were lab-tested. “This technology could make life easier for patients all over the world, while also helping scientists and physicians learn more about how to monitor and treat the disease.”

Flexible mesh encompasses the heart

To ensure the light signals can reach many different parts of the heart, the team created a design that involves encompassing the organ, rather than implanting leads that provide limited points of contact.

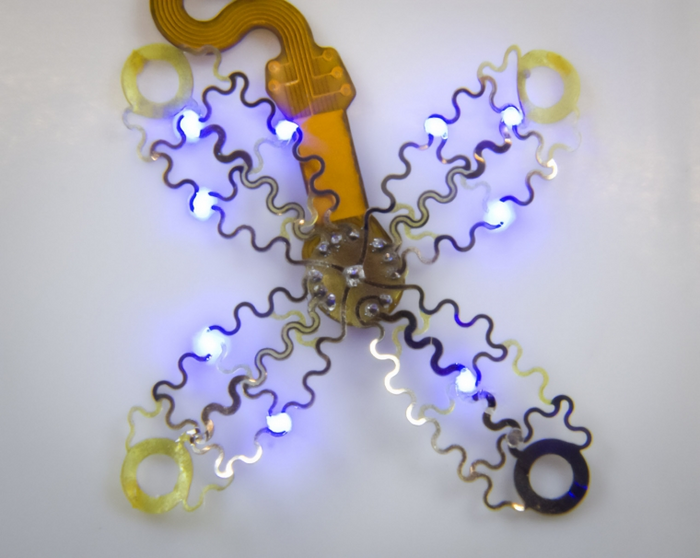

The new pacemaker model consists of four petallike structures made of thin, flexible film, which contain light sources and a recording electrode. The petals, specially designed to accommodate the way the heart changes shape as it beats, fold up around the sides of the organ to envelop it, like a flower closing up at night.

“Current pacemakers record basically a simple threshold, and they will tell you, ‘This is going into arrhythmia, now shock!'” Gutruf said. “But this device has a computer on board where you can input different algorithms that allow you to pace in a more sophisticated way. It’s made for research.”

Because the system uses light to affect the heart, rather than electrical signals, the device can continue recording information even when the pacemaker needs to defibrillate. In current pacemakers, the electrical signal from the defibrillation can interfere with recording capabilities, leaving physicians with an incomplete picture of cardiac episodes. Additionally, the device does not require a battery, which could save pacemaker patients from needing to replace the battery in their device every five to seven years, as is currently the norm.

Gutruf’s team collaborated with researchers at Northwestern University on the project. While the current version of the device has been successfully demonstrated in animal models, the researchers look forward to furthering their work, which could improve the quality of life for millions of people.

The prototype looks like this,

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Wireless, fully implantable cardiac stimulation and recording with on-device computation for closed-loop pacing and defibrillation by Jokubas Ausra, Micah Madrid, Rose T. Yin, Jessica Hanna, Suzanne Arnott, Jaclyn A. Brennan, Roberto Peralta, David Clausen, Jakob A. Bakall, Igor R. Efimov, and Philipp Gutruf. Science Advances 26 Oct 2022 Vol 8, Issue 43 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abq7469

This paper is open access.