Apparently engineers at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst have developed a new kind of memristor. A Sept. 29, 2016 news item on Nanowerk makes the announcement (Note: A link has been removed),

Engineers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst are leading a research team that is developing a new type of nanodevice for computer microprocessors that can mimic the functioning of a biological synapse—the place where a signal passes from one nerve cell to another in the body. The work is featured in the advance online publication of Nature Materials (“Memristors with diffusive dynamics as synaptic emulators for neuromorphic computing”).

Such neuromorphic computing in which microprocessors are configured more like human brains is one of the most promising transformative computing technologies currently under study.

While it doesn’t sound different from any other memristor, that’s misleading. Do read on. A Sept. 27, 2016 University of Massachusetts at Amherst news release, which originated the news item, provides more detail about the researchers and the work,

J. Joshua Yang and Qiangfei Xia are professors in the electrical and computer engineering department in the UMass Amherst College of Engineering. Yang describes the research as part of collaborative work on a new type of memristive device.

Memristive devices are electrical resistance switches that can alter their resistance based on the history of applied voltage and current. These devices can store and process information and offer several key performance characteristics that exceed conventional integrated circuit technology.

“Memristors have become a leading candidate to enable neuromorphic computing by reproducing the functions in biological synapses and neurons in a neural network system, while providing advantages in energy and size,” the researchers say.

Neuromorphic computing—meaning microprocessors configured more like human brains than like traditional computer chips—is one of the most promising transformative computing technologies currently under intensive study. Xia says, “This work opens a new avenue of neuromorphic computing hardware based on memristors.”

They say that most previous work in this field with memristors has not implemented diffusive dynamics without using large standard technology found in integrated circuits commonly used in microprocessors, microcontrollers, static random access memory and other digital logic circuits.

The researchers say they proposed and demonstrated a bio-inspired solution to the diffusive dynamics that is fundamentally different from the standard technology for integrated circuits while sharing great similarities with synapses. They say, “Specifically, we developed a diffusive-type memristor where diffusion of atoms offers a similar dynamics [?] and the needed time-scales as its bio-counterpart, leading to a more faithful emulation of actual synapses, i.e., a true synaptic emulator.”

The researchers say, “The results here provide an encouraging pathway toward synaptic emulation using diffusive memristors for neuromorphic computing.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Memristors with diffusive dynamics as synaptic emulators for neuromorphic computing by Zhongrui Wang, Saumil Joshi, Sergey E. Savel’ev, Hao Jiang, Rivu Midya, Peng Lin, Miao Hu, Ning Ge, John Paul Strachan, Zhiyong Li, Qing Wu, Mark Barnell, Geng-Lin Li, Huolin L. Xin, R. Stanley Williams [emphasis mine], Qiangfei Xia, & J. Joshua Yang. Nature Materials (2016) doi:10.1038/nmat4756 Published online 26 September 2016

This paper is behind a paywall.

I’ve emphasized R. Stanley Williams’ name as he was the lead researcher on the HP Labs team that proved Leon Chua’s 1971 theory about the memristor and exerted engineering control of the memristor in 2008. (Bernard Widrow, in the 1960s, predicted and proved the existence of something he termed a ‘memistor’. Chua arrived at his ‘memristor’ theory independently.)

Austin Silver in a Sept. 29, 2016 posting on The Human OS blog (on the IEEE [Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers] website) delves into this latest memristor research (Note: Links have been removed),

In research published in Nature Materials on 26 September [2016], Yang and his team mimicked a crucial underlying component of how synaptic connections get stronger or weaker: the flow of calcium.

The movement of calcium into or out of the neuronal membrane, neuroscientists have found, directly affects the connection. Chemical processes move the calcium in and out— triggering a long-term change in the synapses’ strength. 2015 research in ACS NanoLetters and Advanced Functional Materials discovered that types of memristors can simulate some of the calcium behavior, but not all.

In the new research, Yang combined two types of memristors in series to create an artificial synapse. The hybrid device more closely mimics biological synapse behavior—the calcium flow in particular, Yang says.

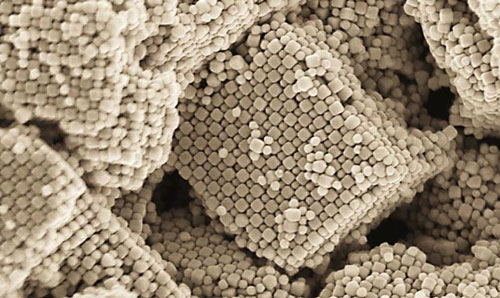

The new memristor used–called a diffusive memristor because atoms in the resistive material move even without an applied voltage when the device is in the high resistance state—was a dielectic film sandwiched between Pt [platinum] or Au [gold] electrodes. The film contained Ag [silver] nanoparticles, which would play the role of calcium in the experiments.

By tracking the movement of the silver nanoparticles inside the diffusive memristor, the researchers noticed a striking similarity to how calcium functions in biological systems.

A voltage pulse to the hybrid device drove silver into the gap between the diffusive memristor’s two electrodes–creating a filament bridge. After the pulse died away, the filament started to break and the silver moved back— resistance increased.

Like the case with calcium, a force made silver go in and a force made silver go out.

To complete the artificial synapse, the researchers connected the diffusive memristor in series to another type of memristor that had been studied before.

When presented with a sequence of voltage pulses with particular timing, the artificial synapse showed the kind of long-term strengthening behavior a real synapse would, according to the researchers. “We think it is sort of a real emulation, rather than simulation because they have the physical similarity,” Yang says.

I was glad to find some additional technical detail about this new memristor and to find the Human OS blog, which is new to me and according to its home page is a “biomedical blog, featuring the wearable sensors, big data analytics, and implanted devices that enable new ventures in personalized medicine.”