This piece of research reminds me of being in a mall explaining data communications to people who’d come to shop. We were part of a nationwide, annual Canadian federal government science promotion effort and the Vancouver region contractor had decided to put science and technology in the malls.

It was very well received and we were busy answering questions throughout the day,, surprising the engineers I worked with. They hadn’t thought anyone would be interested.

We never went back to the mall as things changed a year or two later and the federal government took a more traditional approach to science outreach. I still mourn the loss of an exciting and engaging science promotion initiative.

A March 27, 2019 University of Utah news release (also on EurekAlert) brought the memories tumbling back,

Bring science to people where they are. That’s the driving philosophy that propels U biology professor Nalini Nadkarni to stretch the possibilities of science communication and bring the beauty of science to people and places that others have overlooked.

Building public trust in science is about more than just providing information and improving science literacy, she says. It’s about building relationships between scientists and communities that are founded on shared values. It’s called the “Ambassador Model”, and Nadkarni now has the data to say that the approach works, at relatively low cost and with high effectiveness.

In two recent studies, one published today in BioScience and another published in 2018 in Science Communication, Nadkarni and her colleagues present evidence-based conclusions about the effectiveness of science engagement in two programs: The INSPIRE program, which brings science lectures to prisons, and the STEM [science, technology, engineering and mathematics] Ambassador Program, which trains scientists to engage members of the public in discussions about science.

“Our goal is to help people realize that all citizens are interested in, capable of understanding and full of wonder at science, if it is presented in places and ways that are accessible to them,” Nadkarni says.

A corps of science ambassadors

In the past, the thought went that science and society could be bridged by researchers simply conveying facts to improve science literacy, a one-way communication approach termed the “deficit model”. Communication researchers theorize that a better approach is to consider how people build relationships and enter into productive dialogues. Nadkarni’s STEM Ambassador Program puts these ideas into practice by training scientists to both present the processes of science and to facilitate activities that promote the two-way exchange of ideas, perspectives and experiences with members of the public.

“Just as the U.S. Foreign Service trains ambassadors to represent their home country and build positive relationships abroad,” the STEM Ambassadors homepage says, “scientists can represent their ‘home country’ of science to engage as ‘STEM Ambassadors.'”

Watch STEM Ambassadors talk about their experiences: https://youtu.be/Mzucr_khNow

Find photos of STEM Ambassadors at work here and here.

Launched in 2016, the STEM Ambassador Program (STEMAP) is funded with a $1.3 million grant by the National Science Foundation. Each year, STEMAP, based at the U with Nadkarni as its director, trains cohorts of scientists in the Ambassador Model and helps them develop and implement public engagement of science activities. Since the program began, STEMAP has trained more than 65 scientists in the Ambassador Model. Here’s how it works, step by step:

Scientists first take a close look at themselves and distill their research, personal interests, hobbies and experiences to brainstorm novel connections with a particular community or “focal group”. They learn about the focal group and build relationships by carrying out an “immersion event”. in which they visit group gathering spaces and meet with group representatives. They then apply what they learn to design engagement activities that align with the group’s shared interests, values and practices. They present activities for feedback and ultimately carry out the activities in the focal group’s venue. Finally, scientists reflect on their efforts and evaluate outcomes.

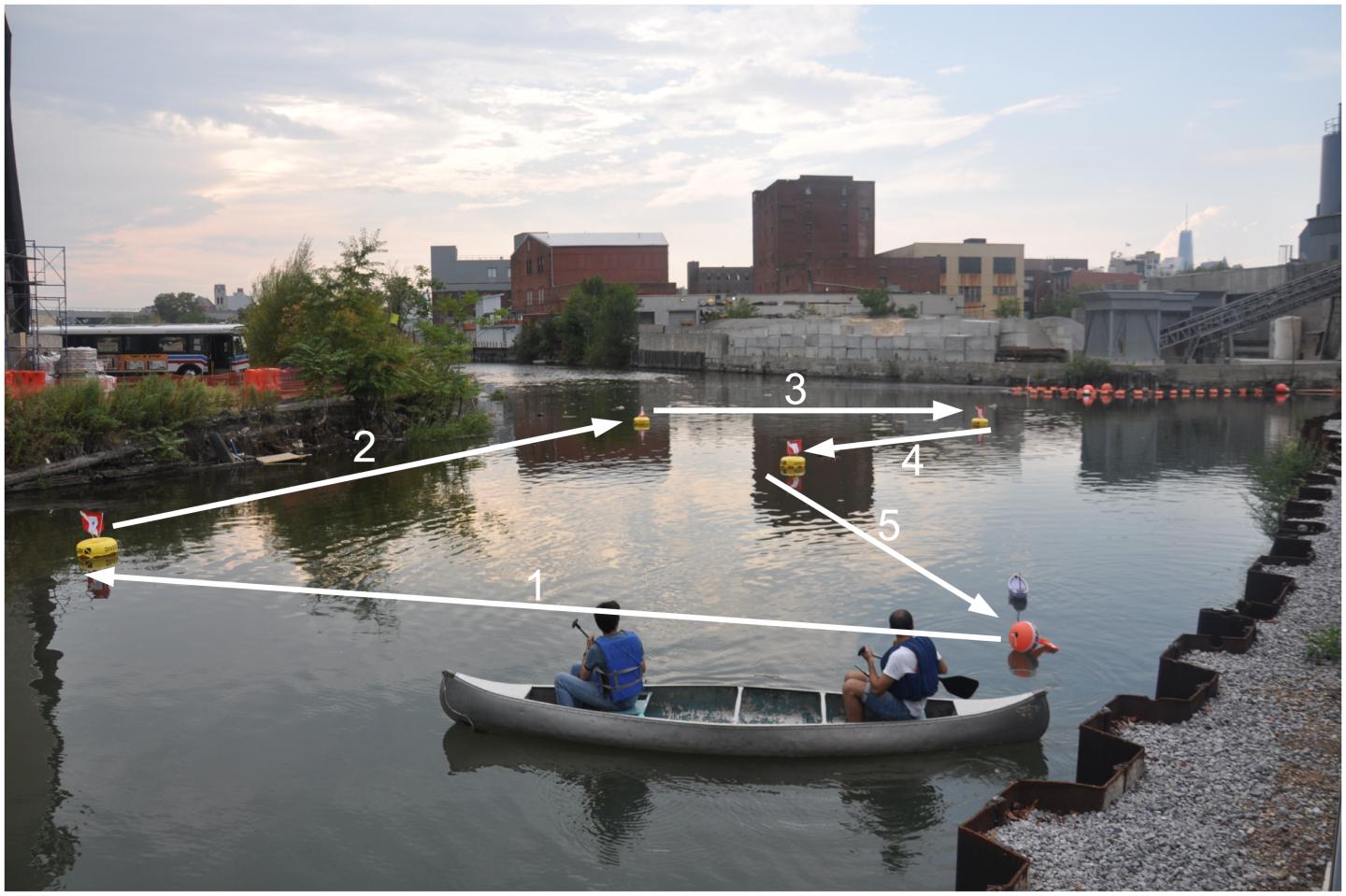

Engagement activities have been as varied as the scientists and focal groups who’ve participated in the program. One ambassador, a microbiologist with an interest in fermentation, served as a co-chef at a local fermentation cooking class and showed participants the microscopic organisms responsible for turning cabbage into sauerkraut. A hydrologist turned her field expedition to Greenland into a book for the children of Kulusuk, a Greenlandic village near her field site. An engineer shared his research to develop more efficient air quality monitoring devices with citizens at a community council meeting and invited them to participate in an air-quality monitoring project [this activity is also known as citizen science]. A mathematician accompanied a group of at-risk youth on a ski trip, and explained the geometry of moving skis to maximize friction.

The assessment of STEMAP’s effectiveness shows strong results. Ninety-seven percent of ambassadors highly valued their participation in the program. More than half went on to plan and carry out additional engagement activities.

The effect on activity participants was also dramatic. Eighty percent said they’d engage in similar events in the future. Seventy-six percent said they were more interested in seeking out scientific information after meeting with an ambassador. And two-thirds said they more strongly considered themselves as someone who can understand and do science.

INSPIRE-ing the incarcerated

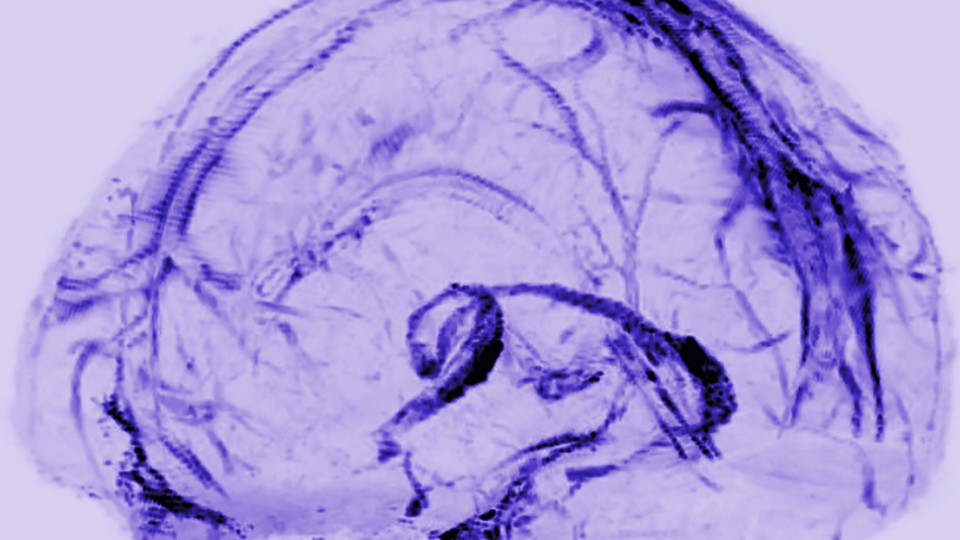

Since 2003, Nadkarni has applied the principles of the Ambassador Model in multifaceted efforts to bring the power of science into the lives of the incarcerated. In 2013, she launched the Initiative to Bring Science Programs to the Incarcerated program, or INSPIRE, in which University of Utah faculty and graduate students present monthly lectures to inmates at the Utah State Prison, the Salt Lake County Jail and five juvenile detention centers in Salt Lake Valley. Topics have ranged from the genetics of pigeon feathers to mathematical modeling of the common cold.

“Our premise is that all people have interest in science, and incarcerated adults and juveniles would probably be no different,” Nadkarni says. And interest has been high–inmates have requested additional lectures, Nadkarni says, and researchers have mentioned feeling that their participation has real impact. But to expand such an approach around the country and catch the attention of correctional institutions and researchers alike, Nadkarni and colleagues would need to publish evidence-based results of INSPIRE’s impact in the scientific literature. And for that, they would need data.

“Without evaluation, we could not publish our findings in the peer-reviewed literature,” she says, “which is necessary if we are to have this work accepted as evidence-based and therefore of interest to other scientists and other corrections institutions.”

With the cooperation of prison staff, Nadkarni and colleague Jeremy Morris surveyed inmates before and after they attended monthly science lectures to assess their knowledge of the science topic as well as their attitudes toward science and math. They also surveyed jail and prison staff and general inmate populations to compare inmates’ attitudes toward science with the general population.

The results offered a surprising glimpse into the science-readiness of inmates. For Nadkarni and her fellow INSPIRE presenters, it was no surprise that inmates displayed a high interest in science (up to 92 percent expressed interest) and an eagerness to learn–even higher than prison and jail staff, who were considered a proxy for the general population.

“They are also interested in meeting with and talking to scientists, and do so with respect,” Nadkarni says. “Their comments and questions indicate that even though many of them have poor formal educational background in science, many have been able to gain knowledge of science and maintain a curiosity about science from other sources.”

The positive impacts of the lecture series–greater science content knowledge, improved attitudes about science and scientists, and increased likelihood of communicating science they have learned with others–were similar to those of formal prison education programs, but required much less of the scientist-instructors.

Based on this past success, INSPIRE is now providing lectures and workshops at youth detention centers as well. Other studies have shown that prison education programs can lower inmates’ chances of returning after release and raise their chances of gaining employment. It’s a model worth sharing.

“We can now bring this to academic and corrections administrators as ‘evidence-based best practices’ with far greater impact than we have been able to muster with only anecdotal or subjective information,” Nadkarni says.

Continuing engagement

Both studies show that achieving the goals of science communication–increased positive views of science, content knowledge and a desire to share with others–are attainable at relatively low cost and in populations that are much more receptive and interested than many might have thought.

And by reaching out to such a wide diversity of groups, both the STEMAP and INSPIRE programs have shown that no one need be considered unreachable by and unengageable with science. After all, Nadkarni writes, there are 6.5 million scientists among the 325 million people in the United States. If every scientist talked about science with just one new person every week, they could reach every single American–in just one year.

Here’s a link to and a citation for Nadkarni’s latest paper,

Beyond the Deficit Model: The Ambassador Approach to Public Engagement by Nalini M Nadkarni, Caitlin Q Weber, Shelley V Goldman, Dennis L Schatz, Sue Allen, Rebecca Menlove. BioScience, biz018, https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biz018 Published: 29 March 2019

This paper appears to be open access.

Here’s a link to and a citation for Nadkarni’s 2018 paper about science outreach and prison populations,

Baseline Attitudes and Impacts of Informal Science Education Lectures on Content Knowledge and Value of Science Among Incarcerated Populations by Nalini M. Nadkarni and Jeremy S. Morris. Science Communication, Volume: 40 issue: 6, page(s): 718-748 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547018806909 Article first published online: October 17, 2018; Issue published: December 1, 2018

This paper is behind a paywall.

For the interested, Dr. Nadkarni has her own website where she has organized and made her academic research and interests, her public engagement work, and her work with incarcerated population accessible.

The eMammal citizen science programs offer children opportunities to use technology to observe nature in new ways. Photo: Matt Zeher.

The eMammal citizen science programs offer children opportunities to use technology to observe nature in new ways. Photo: Matt Zeher.