Points to anyone who recognized the reference to Walt Whitman’s poem, “I sing the body electric,” from his classic collection, Leaves of Grass (1867 edition; h/t Wikipedia entry). I wonder if the cyber physical systems (CPS) work being funded by the US National Science Foundation (NSF) in the US will occasion poetry too.

More practically, a May 15, 2015 news item on Nanowerk, describes two cyber physical systems (CPS) research projects newly funded by the NSF,

Today [May 12, 2015] the National Science Foundation (NSF) announced two, five-year, center-scale awards totaling $8.75 million to advance the state-of-the-art in medical and cyber-physical systems (CPS).

One project will develop “Cyberheart”–a platform for virtual, patient-specific human heart models and associated device therapies that can be used to improve and accelerate medical-device development and testing. The other project will combine teams of microrobots with synthetic cells to perform functions that may one day lead to tissue and organ re-generation.

CPS are engineered systems that are built from, and depend upon, the seamless integration of computation and physical components. Often called the “Internet of Things,” CPS enable capabilities that go beyond the embedded systems of today.

“NSF has been a leader in supporting research in cyber-physical systems, which has provided a foundation for putting the ‘smart’ in health, transportation, energy and infrastructure systems,” said Jim Kurose, head of Computer & Information Science & Engineering at NSF. “We look forward to the results of these two new awards, which paint a new and compelling vision for what’s possible for smart health.”

Cyber-physical systems have the potential to benefit many sectors of our society, including healthcare. While advances in sensors and wearable devices have the capacity to improve aspects of medical care, from disease prevention to emergency response, and synthetic biology and robotics hold the promise of regenerating and maintaining the body in radical new ways, little is known about how advances in CPS can integrate these technologies to improve health outcomes.

These new NSF-funded projects will investigate two very different ways that CPS can be used in the biological and medical realms.

A May 12, 2015 NSF news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, describes the two CPS projects,

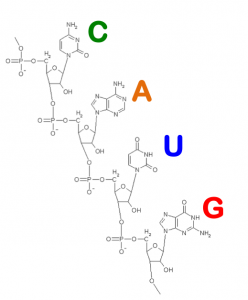

Bio-CPS for engineering living cells

A team of leading computer scientists, roboticists and biologists from Boston University, the University of Pennsylvania and MIT have come together to develop a system that combines the capabilities of nano-scale robots with specially designed synthetic organisms. Together, they believe this hybrid “bio-CPS” will be capable of performing heretofore impossible functions, from microscopic assembly to cell sensing within the body.

“We bring together synthetic biology and micron-scale robotics to engineer the emergence of desired behaviors in populations of bacterial and mammalian cells,” said Calin Belta, a professor of mechanical engineering, systems engineering and bioinformatics at Boston University and principal investigator on the project. “This project will impact several application areas ranging from tissue engineering to drug development.”

The project builds on previous research by each team member in diverse disciplines and early proof-of-concept designs of bio-CPS. According to the team, the research is also driven by recent advances in the emerging field of synthetic biology, in particular the ability to rapidly incorporate new capabilities into simple cells. Researchers so far have not been able to control and coordinate the behavior of synthetic cells in isolation, but the introduction of microrobots that can be externally controlled may be transformative.

In this new project, the team will focus on bio-CPS with the ability to sense, transport and work together. As a demonstration of their idea, they will develop teams of synthetic cell/microrobot hybrids capable of constructing a complex, fabric-like surface.

Vijay Kumar (University of Pennsylvania), Ron Weiss (MIT), and Douglas Densmore (BU) are co-investigators of the project.

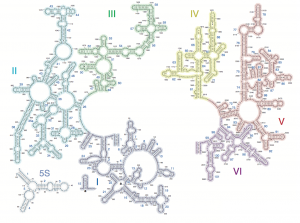

Medical-CPS and the ‘Cyberheart’

CPS such as wearable sensors and implantable devices are already being used to assess health, improve quality of life, provide cost-effective care and potentially speed up disease diagnosis and prevention. [emphasis mine]

Extending these efforts, researchers from seven leading universities and centers are working together to develop far more realistic cardiac and device models than currently exist. This so-called “Cyberheart” platform can be used to test and validate medical devices faster and at a far lower cost than existing methods. CyberHeart also can be used to design safe, patient-specific device therapies, thereby lowering the risk to the patient.

“Innovative ‘virtual’ design methodologies for implantable cardiac medical devices will speed device development and yield safer, more effective devices and device-based therapies, than is currently possible,” said Scott Smolka, a professor of computer science at Stony Brook University and one of the principal investigators on the award.

The group’s approach combines patient-specific computational models of heart dynamics with advanced mathematical techniques for analyzing how these models interact with medical devices. The analytical techniques can be used to detect potential flaws in device behavior early on during the device-design phase, before animal and human trials begin. They also can be used in a clinical setting to optimize device settings on a patient-by-patient basis before devices are implanted.

“We believe that our coordinated, multi-disciplinary approach, which balances theoretical, experimental and practical concerns, will yield transformational results in medical-device design and foundations of cyber-physical system verification,” Smolka said.

The team will develop virtual device models which can be coupled together with virtual heart models to realize a full virtual development platform that can be subjected to computational analysis and simulation techniques. Moreover, they are working with experimentalists who will study the behavior of virtual and actual devices on animals’ hearts.

Co-investigators on the project include Edmund Clarke (Carnegie Mellon University), Elizabeth Cherry (Rochester Institute of Technology), W. Rance Cleaveland (University of Maryland), Flavio Fenton (Georgia Tech), Rahul Mangharam (University of Pennsylvania), Arnab Ray (Fraunhofer Center for Experimental Software Engineering [Germany]) and James Glimm and Radu Grosu (Stony Brook University). Richard A. Gray of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is another key contributor.

It is fascinating to observe how terminology is shifting from pacemakers and deep brain stimulators as implants to “CPS such as wearable sensors and implantable devices … .” A new category has been created, CPS, which conjoins medical devices with other sensing devices such as wearable fitness monitors found in the consumer market. I imagine it’s an attempt to quell fears about injecting strange things into or adding strange things to your body—microrobots and nanorobots partially derived from synthetic biology research which are “… capable of performing heretofore impossible functions, from microscopic assembly to cell sensing within the body.” They’ve also sneaked in a reference to synthetic biology, an area of research where some concerns have been expressed, from my March 19, 2013 post about a poll and synthetic biology concerns,

In our latest survey, conducted in January 2013, three-fourths of respondents say they have heard little or nothing about synthetic biology, a level consistent with that measured in 2010. While initial impressions about the science are largely undefined, these feelings do not necessarily become more positive as respondents learn more. The public has mixed reactions to specific synthetic biology applications, and almost one-third of respondents favor a ban “on synthetic biology research until we better understand its implications and risks,” while 61 percent think the science should move forward.

I imagine that for scientists, 61% in favour of more research is not particularly comforting given how easily and quickly public opinion can shift.