There’s a series of Slate.com articles, under their Future Tense: The Citizen’s Guide to the Future and Futurography programmes, which are the result of a joint partnership between Slate, New America, and Arizona State University (ASU). For the month of Sept. 2016, the topic was nanotechnology.

Introductory articles

Jacob Brogan kicked off the series with his Sept. 6, 2016 article, What the Heck is Nanotech?,

So I know nanotech is both really tiny and a really big deal.

Thanks for getting that joke out of the way.

But also my eyes glaze over whenever someone starts to talk about graphene or nanotubes. What is nanotech, exactly? And should I care?

In the broadest sense, nanotech refers to the deliberate manipulation of matter on an atomic scale. That means it’s arguably as old as our understanding of atoms themselves. To listen to nanoevangelists, the technology could radically transform our experience of material culture, allowing us to assemble anything and everything—food, clothing, and so on—from raw atomic building blocks. That’s a bit fantastical, of course, but even skeptics would admit that nanotech has enabled some cool advances.

Actual conversations around the technology have been building since at least the late 1950s, when famed physicist Richard Feynman gave a seminal talk titled “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom,” in which he laid out the promise of submolecular engineering. In that presentation—and a 1984 follow-up of the same name—Feynman argued that working at the nanoscale would give us tremendous freedom. If we could manipulate atoms properly, he suggested, we could theoretically “write the entire 24 volumes of the Encyclopaedia Brittanica on the head of a pin.”

In that sense, Feynman was literally talking about available space, but what really makes nanotechnology promising is that atomic material sometimes behaves differently at that infinitesimal scale. At that point, quantum effects and other properties start to come into play, allowing us to employ individual atoms in unusual ways. For example, silver particles have antibacterial qualities, allowing them to be employed in washing machines and other appliances. Much of the real practice of nanotech today is focused on exploring these properties, and it’s had a very real impact in all sorts of material science endeavors. The most exciting stuff is still ahead: Engineers believe that single-atom-thick sheets of carbon—the graphene stuff you didn’t want to talk about—might have applications in everything from water purification to electronics fabrication.

You say this stuff is small. How small, exactly?

So small! As the National Nanotechnology Initiative explains, “In the International System of Units, the prefix ‘nano’ means one-billionth, or 10-9; therefore one nanometer is one-billionth of a meter.” To put that into perspective, the NNI notes that a human hair follicle can reach a thickness of 100,000 nanometers. To work at this scale is to work far, far beyond the capacities of the naked eye—and well outside those of conventional microscopes.

Can we even see these things, then?

As it happens, we can, thanks in large part to the development of scanning tunneling microscopes, which allow researchers to create images with resolutions of less than a nanometer. Significantly, these machines can also allow their users to manipulate atoms, which famously enabled the IBM-affiliated physicists Don Eigler and Erhard K. Schweizer to write his company’s logo with 35 individual xenon atoms in 1989.

What I do know about nanotech is that it involves something called gray goo. Gross.

Gray goo is the nanorobot-takeover scenario of the nanotech world. Here’s the gist: Feynman proposed that we could build an ever-smaller series of telepresence tools. The idea is that you make a small, remotely controlled machine that then allows you to make an even smaller machine, and so on until you get all the way down to the nanoscale. By the time you’re at that level, you have machines that are literally moving atoms around and assembling them into other tiny robots.

Feynman treated this as little more than an exciting thought experiment, but others—most notably, perhaps, engineer K. Eric Drexler—took it quite seriously. In his 1986 book Engines of Creation, Drexler proposed that we might be able to do more than build machines capable of manipulating atomic material—autonomous and self-replicating machines that could do all of this work without human intervention. But Drexler also warned that poorly controlled atomic replicators could lead to what he called the “gray goo problem,” in which those tiny machines start to re-create everything in their own image, eradicating all organic life in their path.

Drexler, in other words, helped spark both enthusiasm about the promise of nanotech and popular panic about its risks. Both are probably outsized, relative to the scale at which we’re really working here.

It’s been, like, 30 years since Drexler wrote that book. Do we actually have tiny self-replicating machines yet?

No.

Will we?

Probably not anytime soon, no. And maybe never: In a 2001 Scientific American article, the Nobel Prize–winning scientist Richard E. Smalley articulated something he named the “fat fingers problem”: It would be impracticably difficult to create a machine capable of manipulating individual atoms, since the hypothetical robot would need multiple limbs in order to do its work. The systems controlling those limbs would be larger still, till you get to the point where working at the nanoscale is impractical. Winking back at Feynman, Smalley quipped, “there’s not that much room.”

…

It’s a pretty good overview although there are some curious omissions. Unfortunately, Brogan never does reveal his interview subject’s name. Also, I’m surprised the interviewee left out Norio Taniguchi, a Japanese engineer who in 1974 coined the term ‘nanotechnology’ and Gerd Binnig and Heinrich Rohrer, the IBM scientists in Switzerland who invented the scanning tunneling microscope which made Eigler’s and Schweizer’s achievement possible. As for Richard Feynman and his ‘seminal’ 1959 lecture, that is up for debate according to cultural anthropologist Chris Toumey. From a 2009 Nature Nanotechnology editorial (Nature Nanotechnology 4, 781 [2009] doi:10.1038/nnano.2009.356) Note: Links have been removed,

Chris Toumey has probably done more than anyone to analyse the true impact of ‘Plenty of room’ on the development of nanotechnology by revealing, among other things, that it was only cited seven times in the first two decades after it was first published in the Caltech magazine Engineering and Science in 1960 (ref. 5). However, as nanotechnology emerged as a major area of research following the invention of the scanning tunnelling microscope in 1981, and culminating in the famous IBM paper of 1991, “it needed an authoritative account of its origin,” writes Toumey on page 783. “Pointing back to Feynman’s lecture would give nanotechnology an early date of birth and it would connect nanotechnology to the genius, the personality and the eloquence of Richard P. Feynman.”

Brogan has also produced a ‘cheat-sheet’ in a Sept. 6, 2016 article (A Cheat-Sheet Guide to Nanotechnology) for Slate. It’s a bit problematic. Apparently the only key players worth mentioning are from the US (Angela Belcher, K. Eric Drexler, Don Eigler, Michelle Y. Simmons, Richard Smalley, and Lloyd Whitman. Even using the US as one’s only base for key players, quite a few people have been left out (Chad Mirkin, Mildred Dresselhaus, Mihail [Mike] Rocco, Robert Langer, Omid Farokhzad, John Rogers, and many other US and US-based researchers).

The glossary (or lingo as it’s termed in the article) is also problematic (from the cheat-sheet),

Carbon nanotubes: These extremely strong structures made from sheets of rolled graphene have been used in everything from bicycle components to industrial epoxies.

Unless you happen to know what graphene is, the definition isn’t that helpful. Basically, the cheat-sheet provides an introduction including some pop culture references but you will need to dig deeper if you want to have a reasonable grasp of the terminology and of the field.

Nanomedicine

James Pitt’s Sept. 15, 2016 article, Nanoparticles vs. Cancer, takes some unexpected turns (it’s not all about nanomedicine), Note: Links have been removed,

Nanoparticles’ size makes them particularly useful against foes such as cancer. Unlike normal blood vessels that branch smoothly and flow in the same direction, blood vessels in tumors are a disorderly mess. And just as grime builds up in bad plumbing, nanoparticles, it seems, can be designed to build up in these problem growths.

This quirk of tumors has led to a bewildering number of nanotech-related schemes to kill cancer. The classic approach involves stapling drugs to nanoparticles that ensure delivery to tumors but not to healthy parts of the body. A wilder method involves things like using a special kind of nanoparticle that absorbs infrared light. Shine a laser through the skin on the build-up, and the particles will heat up to fry the tumor from the inside out.

…

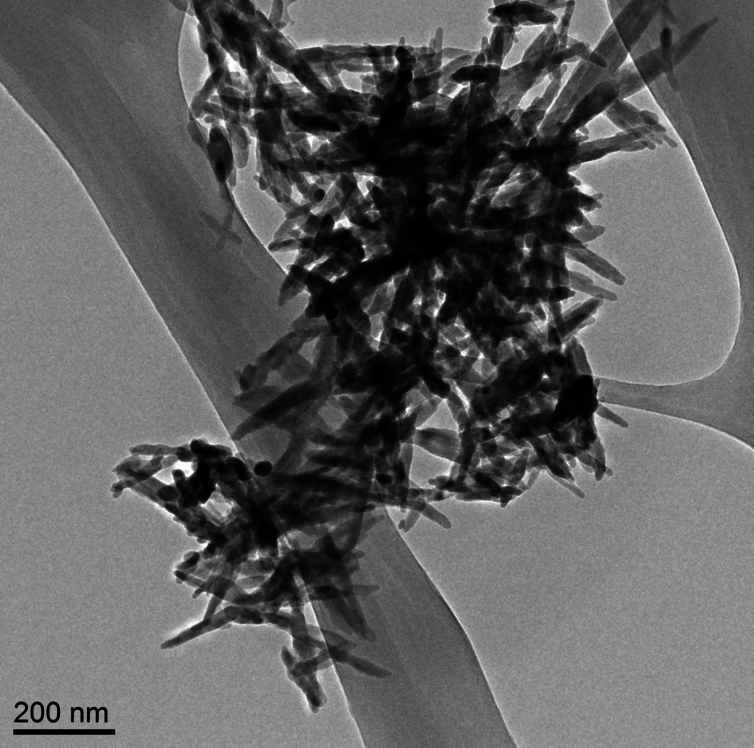

Take nanotubes, tiny superstrong cylinders. Remember using lasers to cook tumors? That involves nanotubes. Researchers also want to use nanotubes to regrow broken bones and connect brains with computers. Although they hold a lot of promise, certain kinds of long carbon nanotubes are the same size and shape as asbestos. Both are fibers thin enough to pierce deep inside the lungs but too long for the immune system to engulf and destroy. Mouse experiments have already suggested that inhaling these nanotubes causes the same harmful effects (such as a particularly deadly form of cancer) as the toxic mineral once widely used in building insulation.

Shorter nanotubes, however, don’t seem to be dangerous. Nanoparticles can be built in all sorts of different ways, and it’s difficult to predict which ones will go bad. Imagine if houses with three bathrooms gave everyone in them lung disease, while houses with two or four bathrooms were safe. It gets to the central difficulty of these nanoscale creations—the unforeseen dangers that could be the difference between biomiracle and bioterror.

Up to this point, Pitt has been, more or less, on topic but then there’s this,

Enter machine learning, that big shiny promise to solve all of our complicated problems. The field holds a lot of potential when it comes to handling questions where there are many possible right answers. Scientists often take inspiration from nature—evolution, ant swarms, even our own brains—to teach machines the rules for making predictions and producing outcomes without explicitly giving them step-by-step programming. Given the right inputs and guidelines, machines can be as good or even better than we are at recognizing and acting on patterns and can do so even faster and on a larger scale than humans alone are capable of pulling off.

…

Here’s how it works. You put different kinds of nanoparticles in with cells and run dozens of experiments changing up variables such as particle lengths, materials, electrical properties, and so on. This gives you a training set.

Then you let your machine-learning algorithm loose to learn from the training set. After a few minutes of computation, it builds a model of what mattered. From there comes the nerve-wracking part; you give the machine a test set—data similar to but separate from your training set—and see how it does.

Pitt has put something interesting together but I think it’s a bit choppy.

Nano and artists

Emily Tamkin in a Sept. 20, 2016 article talks with artist Kate Nichols about her experiences with nanotechnology (Note: Links have been removed),

Kate Nichols is doing something very new—and very old.

The former painter’s apprentice is the first artist-in-residence at the Alivisatos Lab, a nanoscience laboratory at UC [University of California]–Berkeley. She’s made art out of silver nanoparticles, compared Victorian mirror-making technology with today’s nanotechnology, and has grown cellulose from bacteria. Her newest project explores mimesis, or lifelike replication, in both 15th-century paintings and synthetic biology. That work may seem dazzlingly high-tech, but she says it’s in keeping with the most ancient of artistic traditions: creating something new by making materials out of the world around.

…

How did you move from that [being a painter’s apprentice] to using nanomaterials in your art?

It was sort of an organic process that began years before I started working with these materials. It was inspired by two things. One was, I’ve always been intrigued by artists who made their own materials. Going back to early cave painters—the practice of making art didn’t begin with making images, but with selecting and modifying and refining the materials to make art with. When I was studying these Renaissance-era methods of making paint—practicing with these methods, making my own paints in my studio—I began thinking that in many ways, it was sort of like a historical re-enactment. I was using these methods that were developed by these people back in the 1400s. As a person who’s interested in this tradition of painting, what does it mean to be building on that tradition in the 2000s? So I was thinking, well, it seems like the next step would be to develop my own materials that speak to me in my time, with things that they didn’t have access to then.

The second is that back in college, I had to take some sort of quantitative class. I took a math class that I was really fascinated by—modeling biological growth and form. It was taught by a mathematician at Kenyon named Judy Holdener, and Judy studied art before she switched to math. We ended up doing independent study together, and she taught me about the morpho butterfly, which is sort of a poster child for structural color. Having been a painter’s apprentice, I sort of fancied myself a young expert in color. But encountering this butterfly made me realize I had so much more to learn. Color can be generated in other ways than pigmentation. But to create structural color you had to operate on such a small scale. It seemed impossible. But as the years went on I started hearing feature stories about nanotechnology. And I realized these are the people who can create things that small. And that’s how I got the idea.

This article is about one of me favourite topics which is art/science and, happily, it’s a good read. (For anyone interested in her earlier work with colour and blue morpho butterflies, there’s this Feb. 12, 2010 posting.

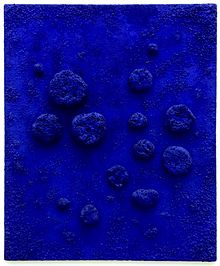

Before heading off to the next topic, here’s one of Nichols’ images,

![Visible Signs of Indeterminate Meaning 14, silver nanoparticle paint and silver mirroring on glass, 12 by 15.5 inches, 2015. These small works on glass are created with silver nanoparticles that Nichols synthesizes and with Victorian-era silver mirroring techniques. Visible Signs of Indeterminate Meaning is the product of carefully planned measurements, calculations, and titrations in a chemistry lab and of spontaneous smears, spills, and erasures in the artist's painting studio. Donald Felton [downloaded from http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2016/09/an_interview_with_kate_nichols_artist_in_residence_at_alivisatos_lab.html]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Futurography_VsiibleSignsOfIndeterminate.jpg)

Visible Signs of Indeterminate Meaning 14, silver nanoparticle paint and silver mirroring on glass, 12 by 15.5 inches, 2015. These small works on glass are created with silver nanoparticles that Nichols synthesizes and with Victorian-era silver mirroring techniques. Visible Signs of Indeterminate Meaning is the product of carefully planned measurements, calculations, and titrations in a chemistry lab and of spontaneous smears, spills, and erasures in the artist’s painting studio. Credit: Donald Felton [downloaded from http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2016/09/an_interview_with_kate_nichols_artist_in_residence_at_alivisatos_lab.html]

Gary Machant’s Sept. 22, 2016 piece about nanomaterial definitions is well written but it’s for an audience who for one reason or another is interested in policy and regulation (Note: Links have been removed),

Consider two recent attempts. Exhibit A is the definition of nanotechnology adopted by the European Union. After much deliberation and struggle, in 2011 the European Commission, which aimed to adopt a “science-based” definition, came up with the following:

A natural, incidental or manufactured material containing particles, in an unbound state or as an aggregate or as an agglomerate and where, for 50% or more of the particles in the number size distribution, one or more external dimensions is in the size range 1 nm [nanometer] – 100 nm. In specific cases and where warranted by concerns for the environment, health, safety or competitiveness the number size distribution threshold of 50% may be replaced by a threshold between 1 and 50%.

Exhibit B is the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s proposed definition of nanomaterials. The regulatory body is scheduled to finalize rules this fall requiring companies that produce or handle nanomaterials to report certain information about such substances to the agency:

[A] chemical substance that is solid at 25 °C and atmospheric pressure that is manufactured or processed in a form where the primary particles, aggregates, or agglomerates are in the size range of 1–100 nm and exhibit unique and novel characteristics or properties because of their size. A reportable chemical substance does not include a chemical substance that only has trace amounts of primary particles, aggregates, or agglomerates in the size range of 1–100 nm, such that the chemical substance does not exhibit the unique and novel characteristics or properties because of particle size.

See the differences? The EPA definition only includes manufactured nanomaterials, but the EU definition includes manufactured, natural, and incidental ones. On the other hand, the EPA defines materials by size (1–100nm) and requires that they exhibit some novel property (like catalytic activity, chemical reactivity, or electric conductivity), while the EU just looks at size. And it goes on with differences in composition requirements, aggregate thresholds, and other characteristics.

These are just two of more than two dozen regulatory definitions of nanotechnology, all differing in important ways: size limits, dimensions (do we regulate in 1-D, 2-D, or 3-D?), properties, etc. These differences can have major practical significance—for example, some commercially important materials (e.g., graphite sheets) may be nanosize in one or two dimensions but not three. The conflicting definitions create confusion and inefficiencies for consumers, companies, and researchers when some substances are defined as nanomaterials under certain programs or nations but not others.

I recommend it if you want a good sense of the nanomaterial policy and regulatory environment.

Nano fatigue

This Sept. 27, 2016 piece by Dr. Andrew Maynard is written in a lightly humourous fashion by someone who’s been working in the nanotechnology field for decades. I have to confess to some embarrassment as I sometimes feel much the same way (“nano’d out”) and I haven’t been at it nearly as long (Note: Links have been removed),

Writing about nanotechnology used to be fun. Now? Not so much. I am, not to put too fine a point on it, nano’d out. And casual conversations with my colleagues suggest I’m not alone: Many of us who’ve been working in the field for more years than we care to remember have become fatigued by a seemingly never-ending cycle of nano-enthusiasm, analysis, critique, despondency, and yet more enthusiasm.

For me, this weariness is partly rooted in a frustration that we’re caught up in a mythology around nanotechnology that is not only disconnected from reality but is regurgitated with Sisyphean regularity. And yet, despite all my fatigue and frustration, I still think we need to talk nano. Just not in the ways we’ve done so in the past.

To explain this, let me go back in time a little. I was first introduced to the nanoscale world in the 1980s as an undergraduate studying physics in the United Kingdom. My entrée wasn’t Eric Drexler’s 1986 work Engines of Creation—which introduced the idea of atom-by-atom manufacturing to many people, and which I didn’t come across until some years later. Instead, for me, it was the then-maturing field of materials science.

This field drew on research in physics and chemistry that extended back to the early 1900s and the development of modern atomic theory. It used emerging science to better understand and predict how the atomic-scale structure of materials affected their physical and chemical behavior. In my classes, I learned about how microscopic features in materials influenced their macroscopic properties. (For example, “microcracks” influence glass’s macro properties like its propensity to shatter, and atomic dislocations affect the hardness of metals.) I also learned how, by creating well-defined nanostructures, we could start to make practical use of some of the more unusual properties of atoms and electrons.

A few years later, in 1989, I was studying environmental nanoparticles as part of my Ph.D. at the University of Cambridge. I was working with colleagues who were engineering nanoparticles to make more effective catalysts. (That is, materials that can help chemical reactions go faster or more efficiently—like the catalysts in vehicle tailpipes.) At the time virtually no one was talking about “nanotechnology.” Yet a lot of people were engaged in what would now be considered nanoscale science and engineering.

Fast forward to the end of the 1990s. Despite nearly a century of research into matter down at the level of individual atoms and molecules, funding agencies suddenly “discovered” nanotechnology. And in doing so, they fundamentally changed the narrative around nanoscale science and engineering. Nanoscale science and engineering (and the various disciplines that contributed to it) were rebranded as “nanotechnology”: a new frontier of discovery, the “next industrial revolution,” an engine of economic growth and job creation, a technology that could do everything from eliminate fossil fuels to cure cancer.

From the perspective of researchers looking for the next grant, nanotechnology became, in the words of one colleague, “a 14-letter fast-track to funding.” Almost overnight, it seemed, chemists, physicists, and materials scientists—even researchers in the biological sciences—became “nanotechnologists.” At least in public. Even these days, I talk to scientists who will privately admit that, to them, nanotechnology is simply a convenient label for what they’ve been doing for years.

The problem was, we were being buoyed along by what is essentially a brand—an idea designed to sell a research agenda.

This wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. Investment in nanotechnology has led to amazing discoveries and the creation of transformative new products. (Case in point: Pretty much every aspect of the digital world we all now depend on relies on nano-engineered devices.) It’s also energized new approaches to science engagement and education. And it’s transformed how we do interdisciplinary research.

But “brand nanotechnology” has also created its own problems. There’s been a constant push to demonstrate its newness, uniqueness, and value; to justify substantial public and private investment in it; and to convince consumers and others of its importance.

This has spilled over into a remarkably persistent drive to ensure nanotechnology’s safety, which is something that I’ve been deeply involved in for many years now. This makes sense, at least on the surface, as some products of nanotechnology have the potential to cause serious harm if not developed and used responsibly. For instance, it appears that carbon nanotubes can cause lung disease if inhaled, or seemingly benign nanoparticles may end up poisoning ecosystems. Yet as soon as you try to regulate “brand nanotechnology,” or study how toxic “brand nanotechnology” is in mice, or predict the environmental impacts of “brand nanotechnology,” things get weird. You can’t treat a brand as a physical thing.

Because of this obsession with “brand nanotechnology” (which of course is just referred to as “nanotechnology”), we seem to be caught up in an endless cycle of nanohype and nanodiscovery, where the promise of nanotech is always just over the horizon, and where the same nanonarrative is repeated with such regularity that it becomes almost myth-like.

I recommend reading the article in its entirety.

Risks

Korin Wheeler discusses nanomaterials and their possible impact on the environment in his Sept. 29, 2016 article. The introduction is a little leisurely but every word proves relevant to the topic (Note: Links have been removed),

Imagine your future self-driving car. You’ll get so much more work done with extra time in your commute, and without a driver, your commute will be safer. Or will it? During your first ride, you probably won’t be able to shake the fear that the software doesn’t know to avoid pedestrians or that you’ll get a ticket because the car ran a light. New technologies are inherently a tangle of exciting possibilities and new risks. We’ve learned from history—and from dinosaurs escaping Jurassic Park—that potential dangers must be evaluated and mitigated before new technologies are released.

Car crashes and T. rex teeth are obvious hazards, but the risks of nanotechnology can be less accessible. Their small size and surprising properties make them difficult to define, discuss, and evaluate. Yet these are the same properties that make nanotechnology so revolutionary and impactful. Nanotechnology is one of the core ideas behind the science of the driverless car and the science fiction of living, 21st-century dinosaurs. Your future self-driving vehicle will likely contain a catalytic converter made efficient by platinum nanomaterials and a self-cleaning paint made possible by titanium dioxide nanomaterials. If electric, the lithium-ion battery may contain nickel magnesium cobalt oxide, or NMC, nanomaterials. If nanotechnology fulfills its promises to reduce emissions, gas requirements, and water use, we will see quality of human life improve, and environmental impacts reduced. But like all progress, nanotechnologies have inherent risk.

…

In evaluating and reducing the environmental risks of nanotechnologies, scientists and engineers are taking a variety of approaches. Studies include two broad classifications of nanomaterials: natural and engineered. Natural nanomaterials have evolved with life on this planet. In our daily lives, they are found in ocean spray, campfire smoke, and even in milk as protein/lipid micelles. It is only in the past few decades, however, that scientists and engineers have been able to accurately make, manipulate, and characterize matter at the atomic scale. These “engineered” nanomaterials designed by scientists and engineers are made for specific applications in well-controlled, reproducible processes. Comparing a naturally occurring and an engineered nanomaterial is like comparing a pebble to a marble. Both are roughly the same size, but they are otherwise very different. Like most anything man-made, engineered nanomaterials are designed with a targeted function and their structure is more uniform, pure, pristine, and well-ordered. These two categories of material can behave and react differently.

Once the nanomaterial is released from manufacturer conditions, it can undergo dramatic changes, including physical, chemical, and biological transformations. As engineered nanomaterials enter the environment, they begin to resemble their natural counterparts. Let’s go back to the example of a marble. If you throw one into a stream, the marble may chip, develop imperfections, and change shape from pounding on rocks. Chemical reactions might strip it of its protective plastic coating. Microorganisms may even be able to take hold to form a new biological surface on the marble. By studying these kinds of complexities and imperfections already present in natural nanomaterials, scientists will be able to predict how these complexities change the behavior and impacts of engineered nanomaterials as well.

…

The diversity and novel properties of engineered nanomaterials affect the way they react and change in the environment. Every single engineered nanomaterial requires an environmental impact study designed to include a range of sizes, shapes, impurities, and surface properties. Since many nanomaterials are essentially small particles suspended in solution (known as “colloidal suspensions”), they can dissolve, join together (or “aggregate”), and undergo surface changes. We don’t have to consider these factors when it comes to more “traditional” molecular structures that are dissolved, like aspirin or table salt. Suddenly, an environmental impact study becomes an exponentially greater task

Read the article in its entirety to get a better sense of the complexity of the issues.

Slate ties up the nanotechnology series in a bow

Jacob Brogan writes up “Six myths about nanotechnology” in his Sept. 29, 2016 article,

1. It’s Not Radically New

…

2. It’s Not a Unified Area of Inquiry

…

3. It’s Not About Any One Tool

…

4. It Doesn’t Make Things Simpler—It Complicates Them

…

5. It Isn’t Necessarily Dangerous

…

6. It’s Still a Useful Term (Probably)

…

Quiz

On Sept. 30, 2016, Brogan produced a quiz (10 questions,

This September, Future Tense has been exploring nanotechnology as part of our ongoing project Futurography, which introduces readers to a new technological or scientific topic each month. Now’s your chance to show us how much you’ve learned.

And, at long last and finally, there is a survey (Sept. 30, 2016),

…

With that [nanotechnology series] behind us, we’d like to hear about your thoughts. What do you think about these issues? Where should the field go from here? Is nanotechnology as such even a thing?

Come back next month [Oct. 2016] for a roundup of your responses. …

Enjoy!

ETA Oct. 11, 2016: Jacob Brogan has written up the results of the survey in an Oct. 7, 2016 piece for Slate. Briefly, the greatest interest is in medical applications and research into aging. People did not seem overly concerned about negative impacts although they didn’t dismiss the possibilities either. There’s more but for that you need to read Brogan’s piece.