This work comes from Rice University (Texas, US) according to an April 17, 2017 news item on Nanowerk,

Microscopic probes developed at Rice University have simplified the process of measuring electrical activity in individual cells of small living animals. The technique allows a single animal like a worm to be tested again and again and could revolutionize data-gathering for disease characterization and drug interactions.

The Rice lab of electrical and computer engineer Jacob Robinson has invented “nanoscale suspended electrode arrays” — aka nano-SPEARs — to give researchers access to electrophysiological signals from the cells of small animals without injuring them. Nano-SPEARs replace glass pipette electrodes that must be aligned by hand each time they are used.”

An April 17, 2017 Rice University news release (also on EurekAltert), which originated the news item, details the work,

“One of the experimental bottlenecks in studying synaptic behavior and degenerative diseases that affect the synapse is performing electrical measurements at those synapses,” Robinson said. “We set out to study large groups of animals under lots of different conditions to screen drugs or test different genetic factors that relate to errors in signaling at those synapses.”

Robinson’s early work at Rice focused on high-quality, high-throughput electrical characterization of individual cells. The new platform adapts the concept to probe the surface cells of nematodes, worms that make up 80 percent of all animals on Earth.

Most of what is known about muscle activity and synaptic transmission in the worms comes from the few studies that successfully used manually aligned glass pipettes to measure electrical activity from individual cells, Robinson said. However, this patch clamp technique requires time-consuming and invasive surgery that could negatively affect the data that is gathered from small research animals.

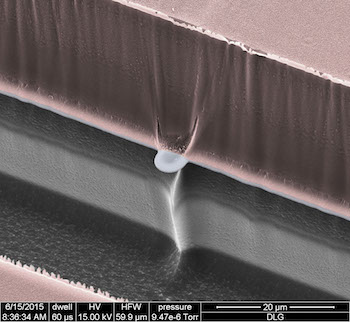

The platform developed by Robinson’s team works something like a toll booth for traveling worms. As each animal passes through a narrow channel, it is temporarily immobilized and pressed against one or several nano-SPEARS that penetrate its body-wall muscle and record electrical activity from nearby cells. That animal is then released, the next is captured and measured, and so on. Robinson said the device proved much faster to use than traditional electrophysiological cell measurement techniques.

The nano-SPEARs are created using standard thin-film deposition procedures and electron-beam or photolithography and can be made from less than 200 nanometers to more than 5 microns thick, depending on the size of animal to be tested. Because the nano-SPEARs can be fabricated on either silicon or glass, the technique easily combines with fluorescence microscopy, Robinson said.

The animals suitable for probing with a nano-SPEAR can be as large as several millimeters, like hydra, cousins of the jellyfish and the subject of an upcoming study. But nematodes known as Caenorhabditis elegans were practical for several reasons: First, Robinson said, they’re small enough to be compatible with microfluidic devices and nanowire electrodes. Second, there were a lot of them down the hall at the lab of Rice colleague Weiwei Zhong, who studies nematodes as transparent, easily manipulated models for signaling pathways that are common to all animals.

“I used to shy away from measuring electrophysiology because the conventional method of patch clamping is so technically challenging,” said Zhong, an assistant professor of biochemistry and cell biology and co-author of the paper. “Only a few graduate students or postdocs can do it. With Jacob’s device, even an undergraduate student can measure electrophysiology.”

“This meshes nicely with the high-throughput phenotyping she does,” Robinson said. “She can now correlate locomotive phenotypes with activity at the muscle cells. We believe that will be useful to study degenerative diseases centered around neuromuscular junctions.”

In fact, the labs have begun doing so. “We are now using this setup to profile worms with neurodegenerative disease models such as Parkinson’s and screen for drugs that reduce the symptoms,” Zhong said. “This would not be possible using the conventional method.”

Initial tests on C. elegans models for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease revealed for the first time clear differences in electrophysiological responses between the two, the researchers reported.

Testing the efficacy of drugs will be helped by the new ability to study small animals for long periods. “What we can do, for the first time, is look at electrical activity over a long period of time and discover interesting patterns of behavior,” Robinson said.

Some worms were studied for up to an hour, and others were tested on multiple days, said lead author Daniel Gonzales, a Rice graduate student in Robinson’s lab who took charge of herding nematodes through the microfluidic devices.

“It was in some way easier than working with isolated cells because the worms are larger and fairly sturdy,” Gonzales said. “With cells, if there’s too much pressure, they die. If they hit a wall, they die. But worms are really sturdy, so it was just a matter of getting them up against the electrodes and keeping them there.”

The team constructed microfluidic arrays with multiple channels that allowed testing of many nematodes at once. In comparison with patch-clamping techniques that limit labs to studying about one animal per hour, Robinson said his team measured as many as 16 nematodes per hour.

“Because this is a silicon-based technology, making arrays and producing recording chambers in high numbers becomes a real possibility,” he said.

A scanning electron micrograph shows a nano-SPEAR suspended midway between layers of silicon (grey) and photoresist material (pink) that form a recording chamber for immobilized nematodes. The high-throughput technology developed at Rice University can be adapted for other small animals and could enhance data-gathering for disease characterization and drug interactions. Courtesy of the Robinson Lab

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Scalable electrophysiology in intact small animals with nanoscale suspended electrode arrays by Daniel L. Gonzales, Krishna N. Badhiwala, Daniel G. Vercosa, Benjamin W. Avants, Zheng Liu, Weiwei Zhong, & Jacob T. Robinson. Nature Nanotechnology (2017) doi:10.1038/nnano.2017.55 Published online 17 April 2017

This paper is behind a paywall.